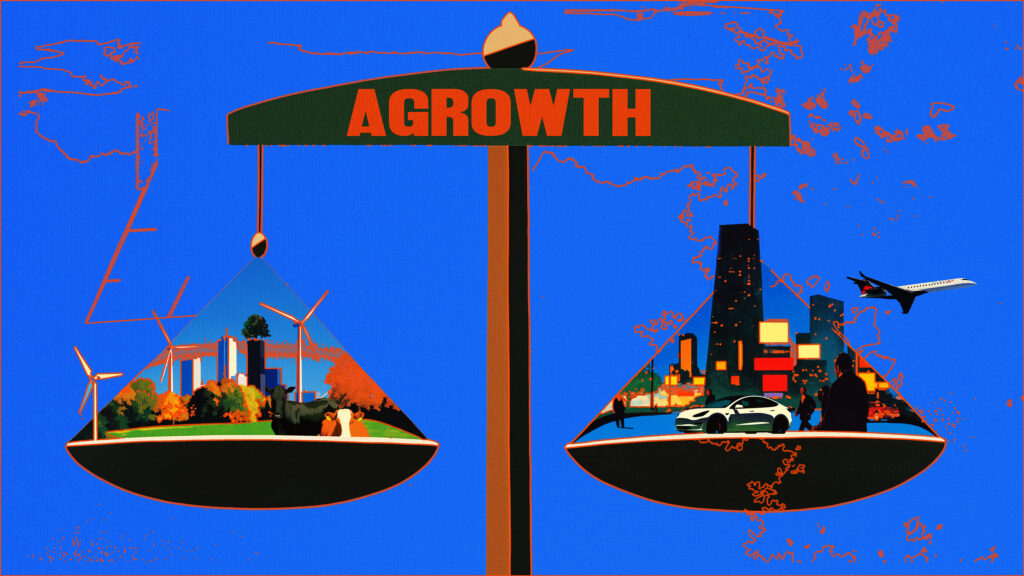

The agrowth paradigm has emerged as a new framework for reconciling economic wellbeing and sustainability.

As an intermediary paradigm between green growth and degrowth, agrowth advocates a pragmatic approach that disengages from the objective of economic growth as a central measure of success without explicitly positing that economic degrowth is necessary in addressing planetary and humanitarian crises. Jeroen van den Bergh, ICREA Professor at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, describes agrowth as “being agnostic about GDP growth, instead focusing on achieving sustainability and human well-being regardless of whether the economy expands or contracts.” Van den Bergh elaborates: “An agrowth strategy allows for targeted contraction in high-emission sectors while supporting expansion in renewable energy and circular economy industries. It provides the flexibility needed to address complex environmental and social challenges while avoiding the potential pitfalls of both continued growth and planned degrowth.” This approach could provide flexibility in addressing EGD sector-specific challenges. For example, in the agriculture sector, this could involve shifting subsidies away from intensive, high-input farming practices towards agroecological methods that prioritize biodiversity, soil health, and rural community well-being. The agrowth paradigm aligns well with emerging concepts in sustainability science, such as Kate Raworth’s “doughnut economics” model. This model provides a visual framework for understanding economic activity that respects both social foundations and ecological ceilings. As Kate Raworth explains in her book “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist”: “The Doughnut consists of two concentric rings: a social foundation, to ensure that no one is left falling short on life’s essentials, and an ecological ceiling, to ensure that humanity does not collectively overshoot the planetary boundaries that protect Earth’s life-supporting systems. Between these two sets of boundaries lies a doughnut-shaped space that is both ecologically safe and socially just – a space in which humanity can thrive.”

By being agnostic about GDP growth, agrowth opposes the pervasive idea that economic growth is a necessary precondition of a livable future. The idea that GDP growth is a viable indicator of humanitarian well-being is increasingly falling under attack, as its stark limitations emerge. The limitations of GDP as a measure of progress become particularly apparent when examining global inequality and environmental trends. Despite decades of economic growth, wealth and income disparities have reached alarming levels. The World Inequality Report 2022 provides stark evidence of this growing divide: “The richest 10% of the global population currently takes 52% of global income, while the poorest half of the population earns 8.5% of it.” This concentration of wealth at the top comes at a significant cost, not just to social cohesion but also to the environment. As economies have grown, so too has their impact on the planet’s ecosystems. This has led some economists to question whether growth, as traditionally measured, is still a desirable goal. In his book “Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development,” Herman Daly, a pioneer of ecological economics, argues: “Growth in GDP has become uneconomic – it now costs more than it is worth at the margin. That is, the environmental and social costs of increased production are growing faster than the benefits, making us poorer, not richer.” Daly’s perspective challenges the conventional wisdom that equates GDP growth with progress. It suggests that beyond a certain point, the pursuit of economic growth may actually be counterproductive, undermining the very foundations of human well-being and planetary health.

“Growth in GDP has become uneconomic – it now costs more than it is worth at the margin. That is, the environmental and social costs of increased production are growing faster than the benefits, making us poorer, not richer.”

This disconnect between GDP growth and overall well-being is evident in various contexts: environmental costs, income inequality, quality of life indicators, and job quality and security. The pursuit of GDP growth has often come at the expense of environmental health, with the Global Footprint Network estimating that we are currently using natural resources at a rate 1.7 times faster than ecosystems can regenerate. In many countries, periods of strong GDP growth have coincided with widening income gaps. Thomas Piketty, in his seminal work “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” demonstrates how the rate of return on capital often exceeds the rate of economic growth, leading to increasing concentration of wealth. Several countries have experienced periods of GDP growth without corresponding improvements in quality of life measures such as health outcomes, education levels, or work-life balance. Moreover, GDP growth often fails to create better jobs or enhance job security, as evidenced by the persistent size of the informal economy. The International Labour Organization reports that as of 2024, over 2 billion people—about 60% of the global workforce—remain employed in informal sectors. This unregulated realm, encompassing street vendors, freelancers, and domestic workers, typically offers low pay, scant legal protections, and substandard working conditions. Women, particularly in developing economies, bear the brunt of this precarity. Even when GDP figures suggest economic improvement, rising living costs, wage stagnation, and wealth concentration often negate potential benefits for the majority. Consequently, economic growth frequently enriches a small segment of society while leaving the broader population struggling, challenging the assumption that a rising GDP tide lifts all boats.

The flexibility of agrowth allows for differentiated industrial policies across sectors, fostering growth in areas such as renewable technologies and advanced manufacturing while promoting contraction in high-impact sectors. However, implementing an agrowth approach necessitates a redefinition of economic governance instruments, particularly regarding progress measurement. The shift beyond GDP, already anticipated by the EU’s Beyond GDP initiative, requires more complex metrics that integrate environmental, social, and distributive data.

Uniting Economic Paradigms: A Synthesized Framework for a Livable Future?

Tim Jackson, Professor of Sustainable Development at the University of Surrey and author of “Post Growth: Life After Capitalism,” suggests a nuanced path forward: “We need to build an economy that allows people to flourish within planetary boundaries.” Moving forward, the EU may need to adopt a hybrid approach that synthesizes insights from all three paradigms. This could involve maintaining green growth strategies in specific sectors crucial for the transition to sustainability, implementing degrowth principles in high-impact sectors where reductions in material and energy throughput are essential, adopting an overall agrowth stance at the macroeconomic level, developing new policy instruments that can navigate the complexities of a post-growth transition, investing in public dialogue and education to build understanding and support for alternative economic approaches, and pioneering new forms of international cooperation based on well-being and ecological sustainability rather than economic growth. Mariana Mazzucato emphasizes the need for bold policy action: “This transition requires not just market-fixing but market-shaping. We need mission-oriented innovation policies that create and shape markets to deliver public purpose.” Kate Raworth concludes with a call to action: “The 21st century calls for a new economic mindset. It’s time to move beyond the growth-versus-degrowth debate and focus on creating economies that are regenerative and distributive by design. The EU, with its commitment to the Green Deal, has the opportunity to lead this transformation.” By embracing elements of degrowth and agrowth alongside targeted green growth strategies, the EU could develop a more nuanced and effective approach to achieving the ambitious goals of the Green Deal. However, this transition will require political courage, public engagement, and a willingness to experiment with new economic models. As the climate crisis accelerates and biodiversity loss continues, the stakes could not be higher. The EU’s ability to navigate this transition could set a precedent for global efforts to create economies that truly serve both people and the planet.