There is a lot of talk around how the capitalist growth model is at the root of most of our climate woes. Lara Frisch looks at 5 alternative economic models that can be applied at a community level.

Gemeinwohl Ökonomie(GWÖ)

Translated into “the Economy of well being” or “Economy of the Common Good”. As the name already suggests, GWÖ is based on constitutional merit of common welfare/common good, which can be found in most constitutions around the world. At its core, GWÖ advocates that the economy is to be at the service of the common good, which contradicts our current economic system. The Austrian economist Christian Felber developed a matrix, which includes five main categories: human dignity, solidarity and justice, ecological sustainability, and transparency and participation. The matrix is based on a point-receiving system and can be applied to communities, companies, schools and even private households. The goal is to reward institutions with a high positive score with benefits like tax reduction, while those institutions that score below an average can get a tax increase f.ex. Because it is so easily applicable, GWÖ is accessible all over the world: from Chile to Australia.

How to join/Weblinks: https://www.ecogood.org

More information:

Christian Felber – Change Everything: Creating an Economy for the Common Good

Doughnut Economics

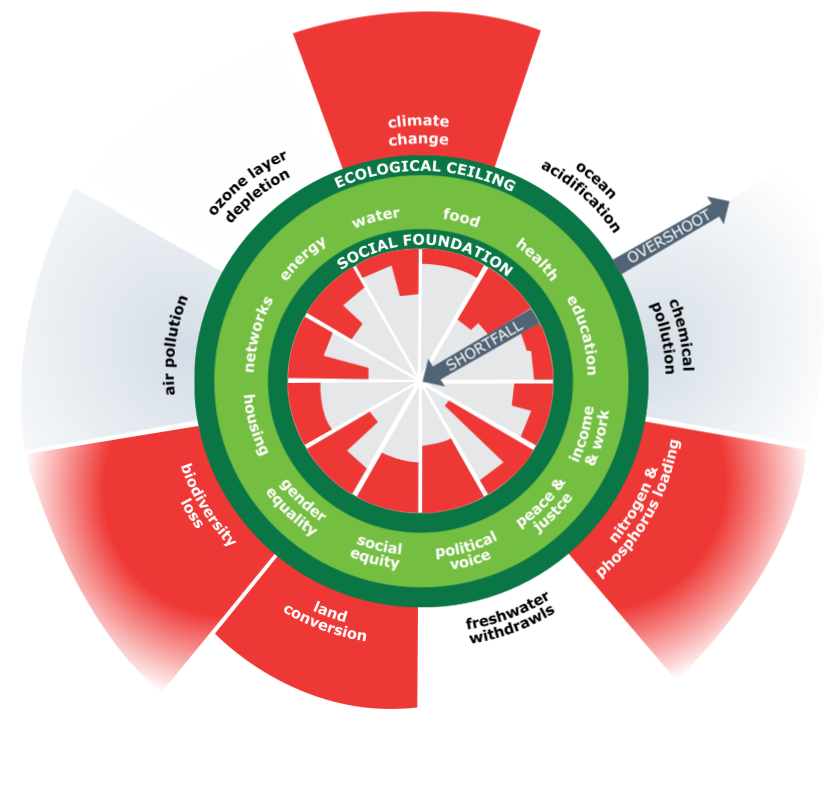

Doughnut Economics is a holistic economic system conceived by the English economist Kate Raworth. The principle idea, which Raworth refers to as being “humanity’s biggest challenge” is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet. The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries is a chart that visualizes the impact of our current global economic system. It depicts nine planetary boundaries, f.ex. climate change, biodiversity loss and air pollution, as well as twelve dimensions of a social foundation, including food, water and housing. The goal of the Doughnut chart is to illustrate a potential balance between our needs and those of the planet. In her TEDx talk, Raworth encourages us to take up this challenge and achieve the seemingly impossible: get all people out of poverty and get humanity as a whole back within the planetary boundaries.

How to join/Weblink: https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/

More information:

Kate Raworth – Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21stEconomist

Postwachstumsökonomie (PWÖ)

PWÖ translates into a post-growth economy and was developed by the German economist Niko Paech. It centres around the idea of reducing consumerism, supporting repairing skills and promoting regional economic production. In short, PWÖ is based on principles of deceleration, decluttering/moderation, communal use/sharing production-consumption, repairing skills and a fruitful local economy. All of these lead to an increase in social justice on a global scale while remaining within the ecological boundaries. This is at its core, the purest form of a sustainable (environmentally and humane) economy. The goals of the PWÖ are to reduce/bisect and reorganize the current industrial production. According to Paech, if we were to follow these principles, this would lead to a bisection of the current industrial production. Scientists agree, in order for us to stay within the 2°C boundary by 2050, a cutting in half of the current industrial production is the minimum.

Image of Niko Paech

How to join/Weblinks: http://www.postwachstumsoekonomie.de

More information:

Niko Paech -Liberation from Excess: The road to a post-growth economy

Commons movement

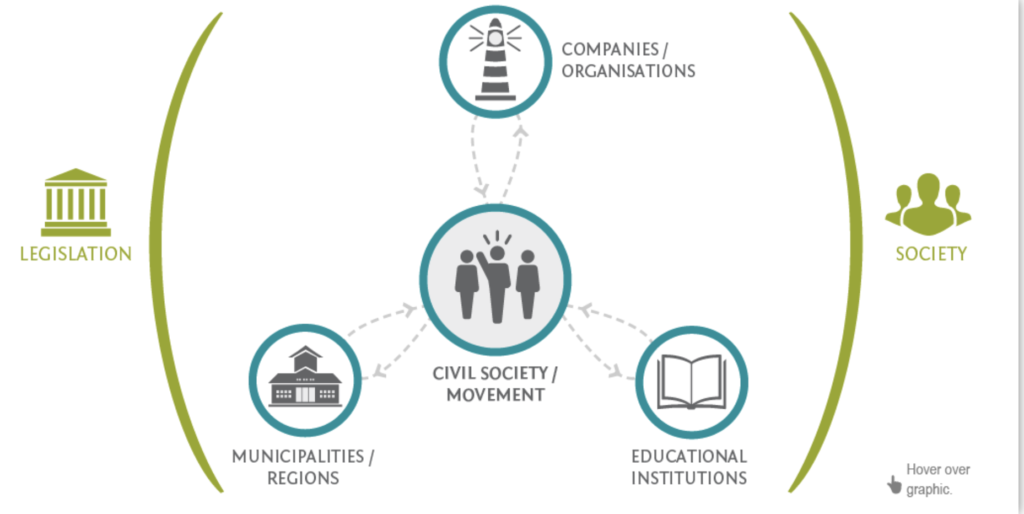

Originally created by the American Nobel prize economist Elinor Ostrom, the Commons Economy, roots itself in self-governance. This massive paradigm shift is accompanied by the belief that all resources are to be communally managed. Ostrom conceptualized this by creating nine principles of Common Pool Resources (CPR), which include the clear definition of resources, their provision and appropriation and the conception of collective decision-making processes.

From there, a Commons Transition movement has been developed by Silke Helfrich and the Henrich-Böll-Foundation. While it still harbours the main principle, it moves away from the legislative economic framework of property law and focuses on expanding the practical side of what it means to share and manage resources within a community. It, therefore, supports self-organized working communities that sustain themselves and their environments by collectively managing resources and promoting new models of production.

How to join/Weblinks: https://primer.commonstransition.org

More info/Literature:

Elinor Ostrom – Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action

Silke Helfrich und Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung- Commons: Für eine Politik Jenseits von Merkt und Staat

Buen Vivir

Buen Vivir is an economic philosophy which originated in indigenous communities around and in Ecuador and Bolivia. ‘Sumak Kawsay’ (Kichwa) or ‘Suma Qamaña’ (Aymara) and ‘Sumak Kawsay’ (Quechua) are just some of the names given to the concept which is loosely translated into Spanish as ‘Buen Vivir’. Similar notions of this concept can be found in Guatemala, Mexico, Panama and Chile. At itscentrer, Buen Vivir is about the harmony that has to exist between human beings themselves and their environment. This diverse movement sees human beings, especially indigenous people as the stewards, even guardians of the earth and its resources. It is a vital economic practice within the individual communities and stands in stark contrast to our Western notion of property. The Buen Vivir movement acknowledges that “the good life” or “good living” is to be considered as something that is undergoing a constant construction and reproduction process, and as such can never fully be attained but always worked towards

.

Image of indigenous communitiespractisingg buen vivir

How to join/Weblinks: https://www.degrowth.info/en/dim/degrowth-in-movements/buen-vivir/

More information:

Mark Burton –Compilationn of Buen Vivir Concepts