Travel has the potential to be a transformative experience for both people and the planet. The question is, how can travel be a force for good?

Sogol Khalkhalian is driven to advocate for endangered people and places through her travels and documentary works. As an interdisciplinary storyteller, she weaves photography, filmmaking, and literature to bring overlooked narratives to light. Her career includes collaborations with National Geographic Magazine, where she has documented the frontlines of climate change—revealing how local and Indigenous communities are impacted by global economic policies, and how both ecological and social survival are at stake. Sogol has also turned her lens toward the everyday struggles and courageous resistance of Iranian women. Her work has since expanded to portray the lives of women across the Middle East, exploring the mutual relationship between the environment and human life. In 2021, she added ‘novelist’ to her many accolades, with the publication of The Last Shahrzad, a work rooted in the ancient epics of her homeland, Iran.

Palestinian-Kuwati writer, artist and teacher, Liane Al Ghusain spoke with Sogol for Icarus Complex Magazine, their conversation covered over ten years of Sogol’s travels, unearthing a critical perspective on adventure and self discovery amidst drastically changing landscapes.

Liane Al Ghusain: What was the first trip you took where it felt “real,” like you were leaving tourism behind?

Sogol Khalkhalian: The first trip I took that didn’t have a touristy feel to it was when I went to Thailand at the age of nineteen. It was a solo trip, a group retreat for yoga. This was the first time I had to share a bed, bathroom, and toilet with people I barely knew. During this ten-day journey, I found myself repeatedly confronting my own obsessions and fussiness. I felt that in order to deal with my anxieties—such as cleanliness, street smells, and food—I had to push myself far outside of my comfort zone.

Through these challenges, I realized that some of my obsessions stemmed from a kind of social superiority complex, and in fact, these behaviors weren’t compulsions but rather forms of fear. Overcoming these fears took years, and in the following years, bit by bit, I became less overwhelmed by these fears, obsessions, and feelings of superiority.

In essence, each journey after that became not only a physical experience but also a transformative process that helped me shed layers of societal conditioning and discover a deeper sense of self.

True travel, for me, isn’t just about visiting a place—it’s about the transformation it brings, the perspective it shifts, and the way it stimulates curiosity and thought.

LAG: With over ten years of travel under your belt, what have you come to learn about mainstream and commercial travel?

SK: Commercial Tourism is often heavily based on pre-planned itineraries, where destination, route and schedule are already set. Yet, we fail to experience the true social environment because everything is focused on the immediate pre-packaged pleasures, leaving no room for self-reflection. A journey, however, can take many forms, ranging from a simple walk from point A to B, to local city trips to traveling to the farthest corners of the earth. Whenever a journey opens up a new worldview for us, I consider it a defining moment that sets it apart from commercial tourism.

Whenever a journey opens up a new worldview for us, I consider it a defining moment that sets it apart from commercial tourism.

LAG: How have your broader cultural studies impacted your approach to life and travel?

SK: I have come to realise the importance of research, before stepping foot anywhere. Alongside traveling, one should read books, watch films and documentaries, listen to music, and gain sufficient knowledge about each destination before embarking on the journey. It’s essential to understand the culture of the place, becoming familiar with various aspects such as food, customs, clothing, and more. For instance, I view food as a social text, from which I can infer people’s relationships and their way of life.

Take the subcontinent of India, for example, where stews are a common dish, and everything is mixed together during its preparation. This shows me that the culture has grown through the blending and coexistence of various traditions. On the other hand, in places where food is served in separate portions, it reflects a culture that constantly divides and creates hierarchies—suggesting that individualism is more pronounced in those societies. In the Far East, the arrangement of food is based on color, such as sushi, whose variety of colors is inspired by the diversity of chakras and chakra colors.

In Central Asia, where a nomadic lifestyle prevailed, the absence of the opportunity to cook elaborate meals resulted in simple, meat-based dishes that were suitable for surviving harsh climates. Meanwhile, in the Middle East, food is prepared based on the principles of ancient Greek medicine and Eastern traditions, where the Humorism properties of ingredients are carefully considered, where spices have played a significant role in the region’s history and culture.

Through all of this, I have learned that food is not just a means of sustenance, but a profound expression of a culture’s values, history, and lifestyle, offering a unique window into how different societies view the world and their place in it.

Alongside traveling, one should read books, watch films and documentaries, listen to music, and gain sufficient knowledge about each destination before embarking on the journey.

LAG: Throughout your travels, you’ve witnessed the ways in which human presence has shaped different environments. Of all the places you’ve been, which have you found to be the most visibly affected by human activity?

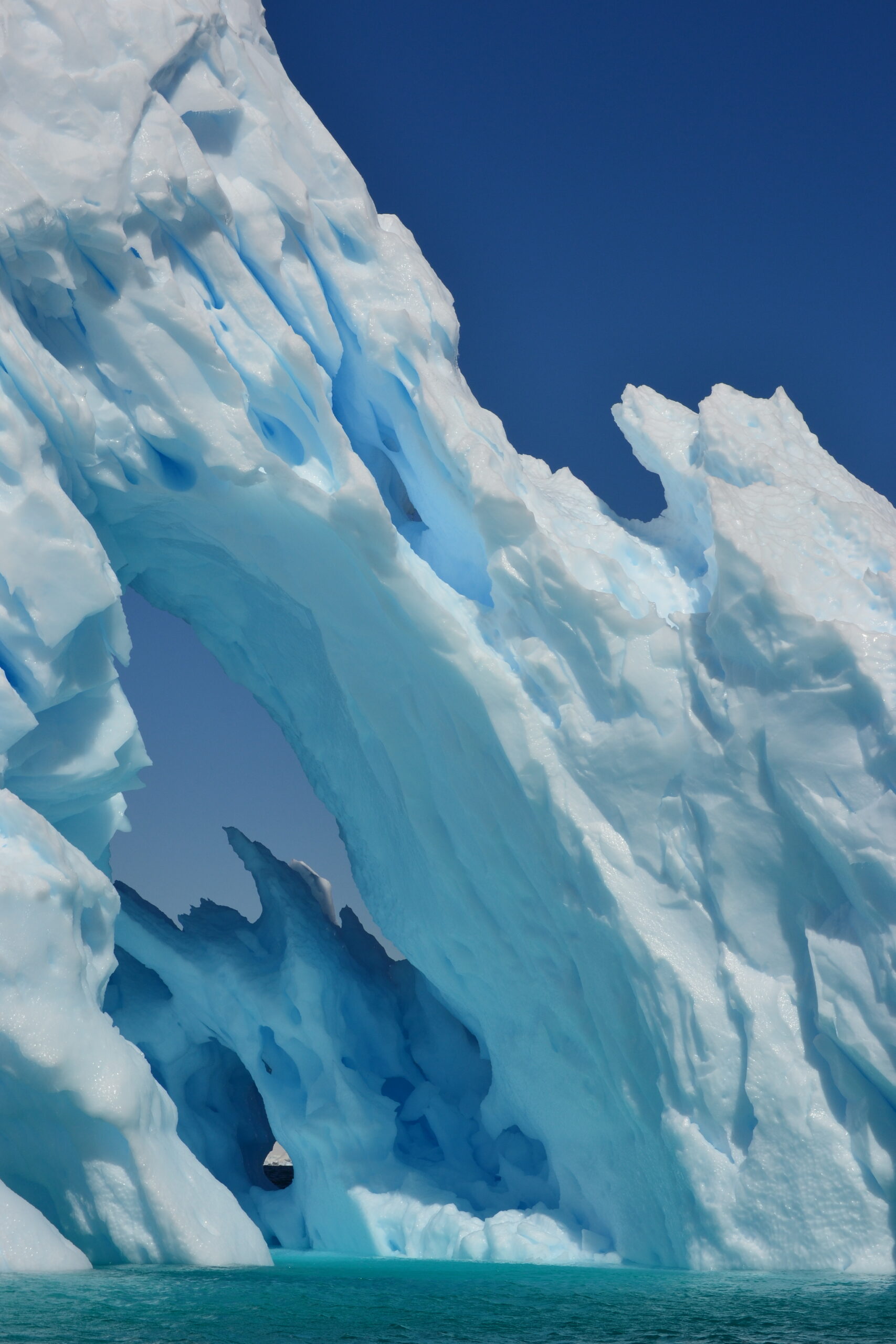

SK: Antarctica was the most pristine place I have ever traveled to. Humans have only set foot there for about 100 years, yet the destructive impacts of human presence are already visible. During my trip, I encountered a whale oil extraction workshop. Although whaling was banned in 1986 under an international agreement, there have still been numerous interventions in Antarctica that have led to the introduction of non-native species, such as certain flies and worms, which now pose a threat to the native wildlife. Additionally, non-native plants have been introduced to the continent, which, along with other factors, has intensified the last few decades of competition between native species and invasive ones for survival.

On top of that, the arrival of rats has led to penguin eggs being eaten, putting the survival of certain penguin species at risk. Climate change and the warming of the surrounding Antarctica waters have further disrupted the delicate balance of the food chain in the region.

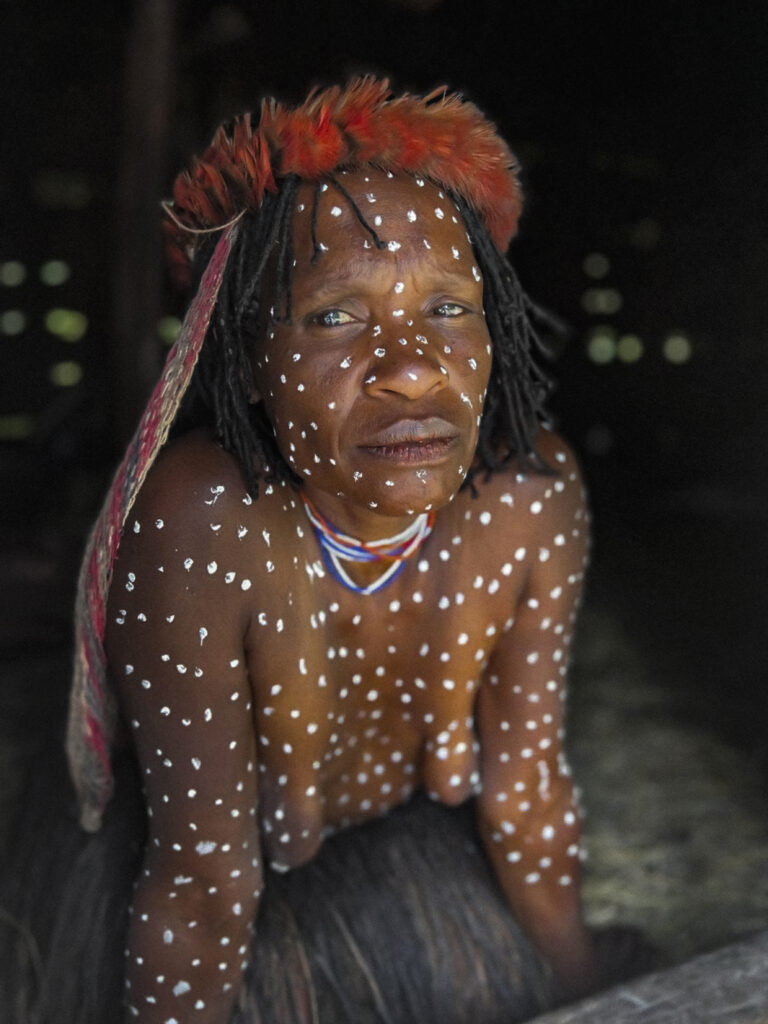

I’ve also traveled to the Amazon rainforest and witnessed how vast areas of forest have been converted into agricultural land. In Siberia, extractive oil and gas activities by Gazprom in the Nenet’s territory have led to microclimate warming and pollution in the region. This, in turn, has resulted in the destruction of the reindeer habitats, putting the Nenet’s way of life at serious risk. In Papua, the tourism industry has had a profound impact on the area’s biological, social, and cultural ecosystems.

To me, all of these situations resemble the butterfly effect—where even the smallest change in one place triggers a series of further escalated changes elsewhere.

The effects of human intervention in this fragile ecosystem are becoming more evident, highlighting the importance of continued conservation efforts. What was once untouched wilderness is now facing challenges from multiple fronts—ranging from invasive species to the broader impacts of global warming. This experience was a stark reminder of the delicate balance of nature and how easily it can be disturbed by even the most well-meaning human actions.

All of these situations resemble the butterfly effect—where even the smallest change in one place triggers a series of further escalated changes elsewhere.

LAG: Your collaborations with National Geographic Magazine have spanned a range of critical environmental issues. Can you tell us about these projects and speak to how your filmmaking and photography serve as a powerful tool for advocacy and bring attention to marginalised narratives?

SK: I have collaborated on several projects with National Geographic Magazine Farsi. These projects primarily focus on climate change and geo-literacy, topics that have long been at the forefront of the organization’s attention. One of the projects compared two of the most extreme locations on Earth—the coldest and the hottest on earth—through photography. The goal was to visually document the impact of climate change on these two contrasting environments. Following that, I worked on a project related to waste management, specifically focusing on the issue of plastic pollution. This project aimed to raise awareness about the excessive consumption and improper disposal of plastic, highlighting its detrimental effects on the environment. Another project I took on was an ascent to Mount Damavand, with the goal of showcasing the region’s rich biodiversity. Given the unique ecosystem of Damavand, this project was especially captivating, as it allowed for the exploration and documentation of the diverse endemic plant and animal species that call this area home.

Through these projects, I have aimed to raise awareness and provoke deeper understanding of the pressing environmental issues facing our planet, from climate change to the challenges of preserving delicate ecosystems.

I have traveled to communities that have been profoundly affected by global economic policies, where both their biological and social existence are deteriorating. My goal in photography and filmmaking is to reflect the voices of these communities. This medium holds great media power, and is capable of drawing attention to these indigenous communities and their struggles.

Through my work, I aim to shed light on the unseen, giving a platform to those whose stories are often overlooked or unheard. The ability to tell their stories through images and film is not just a form of art but a means of advocacy and awareness. It’s a calling to bring their realities to the forefront, allowing their voices to be heard in a world that often disregards them. For me, amplifying the voices of communities rendered voiceless has become the most important purpose of my life.

LAG: Your project The Last Moment and how you see photography and film as tools for preservation and advocacy?

SK: In the project The Last Moment, I have focused on how the processes of globalization are putting many aspects of our world at risk of disappearing. From the pristine nature of Antarctica to the unique religion of the Kalash people, and the traditional way of life in Siberia—everything is under threat. As a result, I have tried to approach this project through a photographic and film archive, aiming to document and reflect on these cultural and social events. The ultimate goal is to amplify the voices of those who have been silenced, to bring attention to their struggles and to preserve their stories before they are lost to time.

This project isn’t just about documenting what’s disappearing; it’s about raising awareness and sparking a conversation around the importance of protecting these diverse cultures and environments. The voices of these communities need to be heard, and through this archive, I hope to offer a platform for their stories to endure.

LAG: You’re also a novelist, and your 2021 book The Last Shahrzad has its roots in ancient Iranian epic storytelling. Could you tell us more about the role that history/myth/culture play in your work?

SK: I believe Mount Damavand is the cultural root of us Iranians. When I spent a night climbing to its summit, I heard roars that, according to local folklore, were attributed to the voice of Zahhak—an evil mythical king and a symbol of the devil (in reality these sounds belong to volcanic activities of mount Damavand). This experience sparked a deeper interest in reading myths for me. The Last Shahrzad is a story about a girl who is thrust from the present into the past. In this era, the sun has been stolen, and the forces of darkness have taken over the Earth. With the help of good spirits, Shahrzad is able to turn the wheels of history back and usher in a new age of light.

Writing this book and immersing myself in Iranian mythology was an extraordinary experience—almost like traveling, but within the realm of my imagination. I am deeply fascinated by superstitions and folk tales in every place I visit. While superstitions are often not taken seriously, they serve as an oral history of a culture’s untold stories—stories that are deeply entwined with the mythological, religious, and cultural heritage of a community. These tales, often dismissed as mere folklore, carry profound layers of wisdom and historical insight into the soul of a people.

Everything I explore, whether through photography or research, is intertwined, forming a cohesive narrative that reflects the complexities of both human experiences and the world we live in.

LAG: What do you think is the role of the artist or storyteller in our current global moment? And, in what ways do you feel that others are inspired by your travels?

SK: To me, an artist is someone who knows the art of living. And for me, the art of life means taking care of myself and those around me. The highest form of art is the ability to give love and to receive love in return. Living authentically and creating a space for love to flourish—these are the true expressions of artistry.

I don’t believe I am a social model or a role model for others. My most important teacher has been nature, and its cycles have taught me that life is constantly in motion, and we must find balance and harmony between all things. As a result, whenever someone asks me this question, I tell them to look to nature. Each person will find their own lesson within it. Everyone has their own unique journey, and nature offers a mirror through which we can all reflect, learn, and grow.