When Art Jameel convened a meeting of museums based in the Middle East, they discovered that there were no guidelines on commissioning, displaying, and conserving art in extreme climate conditions.

Institutions facing the brunt of the climate crisis were having to work with Eurocentric protocols that were not fit for purpose. Under the guidance of director Antonia Carver, Art Jameel is working to change this, alongside making a commitment to a formal sustainability charter that attempts to weave environmental awareness and climate mitigation into every element of the foundation’s activities.

Anna Souter: Could you start by telling me a bit about Art Jameel and its overarching aims?

Antonia Carver: Art Jameel was founded to support artists and creative communities, as well as to establish centres of learning where we can bring the arts to the broadest possible audiences. It is founded on the idea that the arts are fundamental to understanding who we are and imagining a future. And thinking about how the climate crisis, sustainability, and biodiversity intersects with everything we do.

We were originally set up as part of Community Jameel, which is the Jameel family’s philanthropic arm, then we established Art Jameel as a parallel but interconnected entity. We began by working with other institutions, artists, and communities to realise projects, then in 2018, we established Art Jameel Centre, Dubai’s contemporary arts museum. It’s a place that generates knowledge from the ground up, positioning learning, research, and exhibition-making on an equal footing through the institution. Following this, we opened Hayy Jameel in Jeddah in Saudi Arabia in 2021, which is an interdisciplinary neighbourhood including exhibition spaces, an independent cinema, children’s learning centre, and artist studios.

AS: And you recently launched a Sustainability Charter?

AC: Yes, so when we started building our buildings, we were influenced by the architects we were working with, particularly Wael Al Awar. He was interested in asking not only how our visitors were going to interact with the buildings and the works on display, but also how you might create buildings that interface between cultural experiences and ecology, even in the middle of large port cities like Dubai and Jeddah.

That philosophy is now woven through everything we do. We’re looking at how to make our buildings as sustainable as possible, and we’re also trying to think through the role of the arts when it comes to engaging with the climate crisis. We want our visitors to consider themselves active participants rather than passive observers.

The final strand to our Sustainability Charter is thinking about original research from our part of the world. So rather than absorbing a narrative that’s given to us by institutions or cultural thinking in the Global North, we are asking questions about our environment and circumstances here in the Middle East and more broadly across the Global South. And that has a philosophical angle to it as well as a very practical research angle.

We want our visitors to consider themselves active participants rather than passive observers.

AS: I was struck by how the charter combines information about practical steps taken to reduce emissions with details about exhibitions exploring eco-political issues, alongside more philosophical questions about operating in Art Jameel’s specific context. It is made clear that environmental challenges can’t be separated from social, cultural, and structural ones. Could you give some examples of these challenges and how they’re addressed in Art Jameel’s programming?

AC: It’s important to think about these things in a very broad context. We learned a lot from convening a culture and climate summit in 2023, in which we brought together arts and ecology leaders with institutional leaders from across the Middle East. We were trying to examine what the climate crisis looks like from our part of the world, and we realised how different these crises can look from here. So rather than absorb a narrative imported from elsewhere, we understood that it was essential to think from the ground up.

For example, colleagues from places such as Lebanon, where state-provided power is very intermittent, were saying that being able to get off the grid and have their own alternative renewable energy resources was essential to keep their institutions going. It’s not only a matter of climate survival, it is a matter of survival per se. If they can generate their own power, they can extend their opening hours, they can protect their artworks, they can keep the lights on and be there for the public.

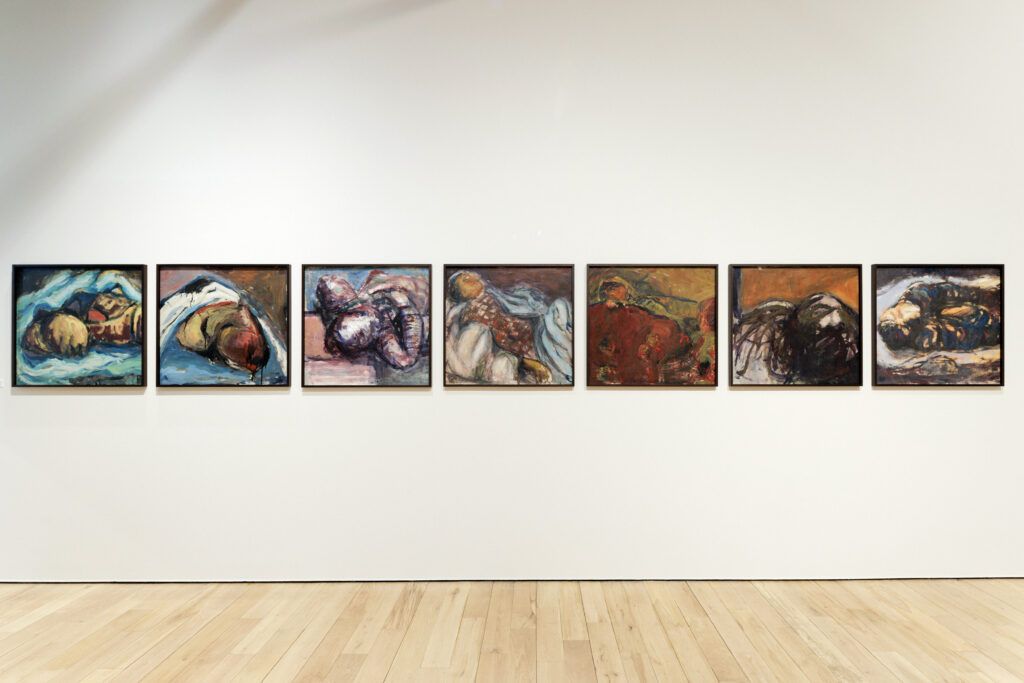

Some of the organizations we’ve been working with are based in Palestine. And you wonder, in a time of genocide, why would people be thinking about the climate crisis? But speaking to colleagues there, they see the need to care for land, for environment, and for people as fundamentally intertwined. One of our current exhibitions by Gaza-based artist collective Eltiqa shows the ways in which Palestinian people are still foregrounding a future; despite living an absolutely nightmare present, they are still thinking collectively about a future that’s not only for them but for the planet as a whole. I find that so inspiring.

So maybe terms like “intersectionality” can seem modish in the West, but we see these intersectional relationships being played out constantly in our region from the perspective of necessity, not just terminology.

Colleagues from places such as Lebanon, where state-provided power is very intermittent, were saying that being able to get off the grid and have their own alternative renewable energy resources was essential to keep their institutions going. It’s not only a matter of climate survival, it is a matter of survival per se.

AS: Your current programming has an emphasis on land rights, including the exhibition of work by Eltiqa you just mentioned, and also a solo retrospective by Spanish artist Asunción Molinos Gordo titled The Peasant, The Scholar, and the Engineer. Why does this question of land feel so important right now?

AC: Asunción Molinos Gordo is so interesting in her thinking around “contemporary peasantry”. It’s an idea of really learning from the people who are closest to the land, such as farmers and labourers. Rather than relegating their knowledge to the past, she advocates recognising it as a cultural knowledge that’s fundamental to our times.

We’ve learned a lot from working with Adib Dada, a Lebanese architect and forest maker, as he describes himself. We worked with him on a commission for our park Tarabot, which is a living forum exploring our relationship with other species right in the heart of the city. Dada’s outlook on the ecological crisis is to turn it around to talk about abundance rather than lack. He has built an incredible dome that gives back more to the environment than it extracts. It’s a steel structure, shaped and treated in a way that when we sink it in the sea, which we’re going to do in soon, it will generate a coral reef and become a centre for coral regeneration.

And the other materials that are used in the structure are all pioneering new alternatives to commonplace carbon-intensive building materials. For example, there’s “datecrete” – a concrete-like substance made from date pits. There’s also a mycelium-based material made from coffee grounds from our restaurants, and “desert board”, which is a wood substitute made from palm waste. That one has really taken off recently, partly through this project. So that’s a typical example of how we try to commission artwork that is also regenerative in itself, generating new kinds of thinking.

AS: That sounds fascinating. Is there a balance to be struck between working to mitigate or avoid contributing to the climate crisis on the one hand, and also preparing for a future that will inevitably be impacted by climate breakdown on the other?

AC: We are collecting, commissioning, and exhibiting artworks connected to the climate crisis in a desert environment and in an oil economy, and that can feel like a paradox. But the UAE in particular is very forward-thinking when it comes to considering how we are going to survive and live in the future. There’s a future-oriented momentum here, and the arts are deeply connected with that. We need to start asking the questions that seem unthinkable in our industry.

There’s an awareness across Asia and the Middle East that the climate crisis has already arrived, and it is going to affect us more obviously in our part of the world sooner than elsewhere. But at the same time, institutions in Europe and the UK, for example, are very aware that they’ve been recording the hottest summers on record, and that their artworks are reacting differently to these kinds of environments. So this is not something we have to shoulder alone.

There’s a future-oriented momentum here, and the arts are deeply connected with that. We need to start asking the questions that seem unthinkable in our industry.

AS: There’s clearly a pressing need to reconsider museum practices in the context of extreme conditions. What are some of the key challenges here?

AC: Over the last year, we’ve started a Collection Care Fellowship, a new programme looking at collection care in climatic extremes. Dubai, for example, where we keep our collection, is extremely hot in the summer and extremely humid year-round. To cool and dehumidify our buildings to reach the Eurocentric museum standards set by the Global North, we have to pour infinite resources into that process, which really affects our attempts to reduce our carbon footprint.

We’re trying to question how we develop our own methods of collection care from the perspective of the Global South. For instance, how can we advance our knowledge about caring for works in humid zones, setting our own guidelines on temperature and humidity controls? Or can we find locally available alternative materials for packing, storing, and transporting artworks, rather than flying them in?

These are issues that are shared across the places where culture and museum-building are growth areas, such as China, the Gulf, and parts of Africa. New museums are being built in places which already have an awareness of the realities of the climate crisis, and it’s radically challenging institutional thinking.

The overriding museum philosophy based on the precedent of the Global North is that museums should amass objects which must be kept forever as a means of defining humanity. If they’re too fragile to be seen, then they must be kept in storage for future generations. We’re interested in challenging this philosophy of storing for the future, which often pulls away from an emphasis on displaying and talking about works with a sense of urgency that is fitting to the climate crisis.