Criminalising ecocide is about recognising that when ecosystems collapse, so too do the conditions for human dignity.

“It’s been four years since we’ve been able to harvest Yam in Yakel…When we do not have the Yam and other crops, our body will grow weak and if we have a good garden, our bodies will be strong. Now our bodies are growing weak…Yam is something that is related to the spirits within me…it’s the bad sun and the bad rain that’s affecting the Yam.”

These are the words of Alpi Nangia, a farmer from Vanuatu testifying before the International Court of Justice about the effects of climate change. For Alpi Nangia and the people of the Pacific, the climate crisis is not an abstract debate nor a distant forecast. It is a lived reality—a steady erosion of the conditions that make a full life possible. What is happening in Vanuatu, Fiji, and across the Pacific is not only a story of climate vulnerability. It is also a warning to the world that environmental collapse undermines the most basic human rights.

And yet, while the deliberate destruction of a village in war can be prosecuted as a crime against humanity, the knowing destruction of an entire ecosystem on which communities depend is not recognised as a crime at all.

This is the gap that the movement for ecocide law seeks to fill. The argument is simple: the gravest forms of environmental destruction are also grave violations of human rights, and international law must evolve to reflect that truth.

Human well-being and nature are inseparable

There was once a time when environmental issues were thought of as separate from questions of justice or rights. But today, there is growing recognition that human well-being and the natural world are inseparably linked.

Polluted air is not just an environmental issue; it is a health crisis. Deforestation is not only about vanishing species; it is about Indigenous Peoples losing their homes, cultures, and livelihoods. Melting glaciers and intensifying storms are not simply physical phenomena; they are forces that displace millions, pushing them into precarious futures as climate migrants.

Seen through this lens, environmental collapse is not merely an ecological crisis. It is also a human rights crisis: a threat to life, health, housing, food, culture, and the ability to live in dignity. And as with so many global harms, its impacts are not borne equally. Marginalised populations are often hit first and worst: Indigenous communities who depend directly on threatened ecosystems, small island nations facing rising seas and crop failures, like the vanishing yams of Vanuatu, and low-income neighborhoods exposed to industrial pollution. A human rights approach reveals this social, often racialised, inequality and demands a justice-centered response.

International law is catching up

International law is beginning to reflect these realities. In 2022, the United Nations General Assembly formally recognised the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.

In July of this year, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued a landmark advisory opinion affirming that states have an obligation to prevent irreversible environmental harm, and it recognised that duty as jus cogens, a peremptory norm of international law, on par with the bans on slavery and genocide.

This was followed just a few weeks later by the long-awaited advisory opinion on climate change from the International Court of Justice. Requested by Vanuatu and supported by more than 130 countries, the Court affirmed that states have binding obligations, including under human rights law, to prevent harm to the climate system and the resulting impact on life and well-being. In invoking lived realities like those voiced by Alpi Nangia, the Court underscored that climate harm is not theoretical—it is already undermining rights, health, and cultures.

The missing crime

Still, there is a gaping hole at the heart of international criminal law. Environmental destruction is currently prosecutable at the International Criminal Court only in limited circumstances during armed conflict or when directly linked to harm against humans. There is no category of crime that recognises the intrinsic wrong of severe, widespread, or long-term environmental damage itself.

After the Second World War, the global community recognised that the worst human rights violations — genocide, crimes against humanity— were so serious that they must be elevated into crimes under international law. Today, with the interdependence of human rights and the environment now undeniable, calls are growing to recognise the worst ecological harms in the same way. The missing crime is ecocide.

The movement to criminalise ecocide is being led not by the powerful states that built the post-war legal order, but by those most vulnerable to its failure.

In September 2024, Vanuatu, Fiji, and Samoa formally proposed ecocide as the fifth core crime under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. These Pacific Island nations, on the front lines of rising seas, freshwater salinisation, and intensifying storms, were not simply asking for environmental safeguards. They were asserting that mass environmental destruction constitutes a profound violation of human rights: the rights to life, health, housing, to self-determination as a nation, and to a viable environment in which communities can survive and thrive. Their proposal echoed the lived testimony of Alpi Nangia: when yams disappear, when gardens no longer feed bodies or spirits, when seas take away land, survival itself is at stake. By elevating ecocide to the level of genocide or crimes against humanity, Vanuatu and its neighbors were not only advocating for themselves: they were speaking for all humanity.

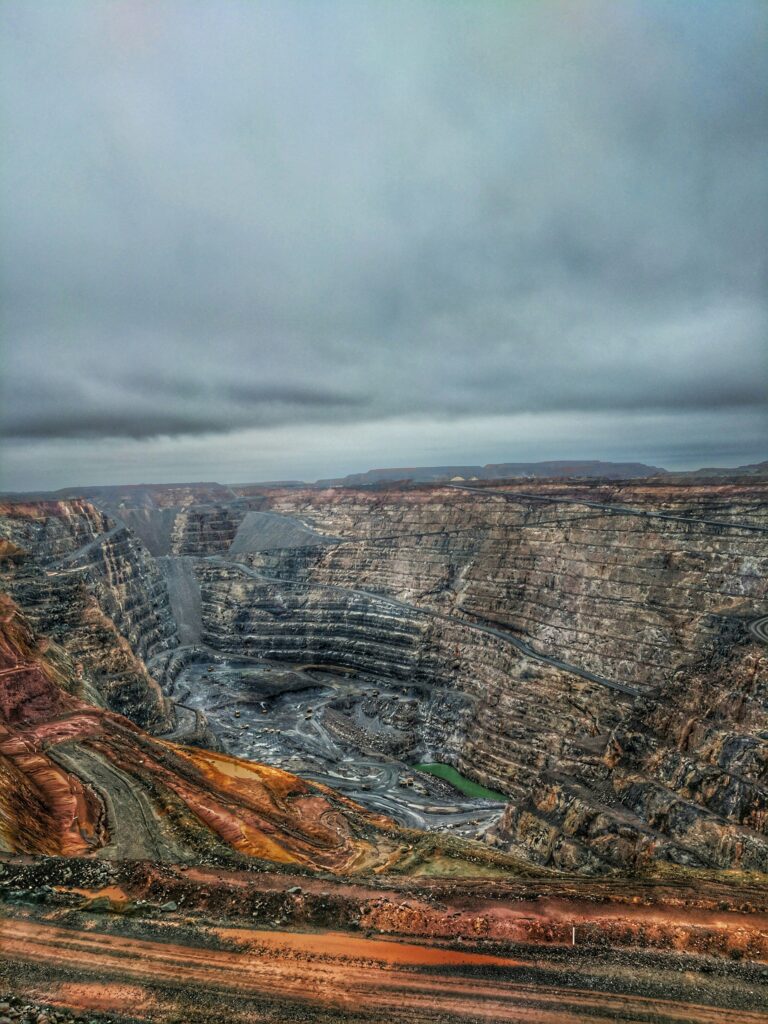

Weeks later, the Democratic Republic of the Congo added its voice. Facing deforestation, illegal mining, disrupted rainfall, and mounting threats to the Congo Basin forest, a critical ecosystem sustaining more than 80 million people, the DRC underscored that environmental destruction often stems from global inequities: the demand for minerals fueling multinational supply chains headquartered in the global north, far from the sites of harm.

The proposed definition of ecocide, crafted by an Independent Expert Panel in 2021, describes “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts.” As one of the panel’s members, I worked with colleagues from around the world to set a threshold that is both principled and practicable. At its heart lies the irrefutable truth that human well-being is inseparable from the health of the natural world.

Momentum is building. In 2024, the European Union adopted a revised Environmental Crime Directive requiring member states to criminalise acts “comparable to ecocide” by 2026. In 2025, the Council of Europe adopted a treaty on environmental crime that obliges states to prosecute intentional conduct resulting in disasters “tantamount to ecocide.” New ecocide bills are being introduced almost weekly—from Italy and the Netherlands to Peru, French Polynesia, Argentina, and Scotland.

This shift is echoed by international courts. But while the Inter-American Court and ICJ have affirmed states’ obligations to prevent irreversible environmental harm, neither addresses individual criminal liability. That is the role of the ICC. Ecocide law would fill this accountability gap by enabling the prosecution of political and corporate decision-makers whose actions cause severe and widespread harm. It reflects the growing maturity of international law: from post-war prohibitions on atrocities against people, to twenty-first century safeguards for the conditions of life itself.

Ecocide is a human rights imperative

Criminalising ecocide is about recognising that when ecosystems collapse, so too do the conditions for human dignity.

Environmental destruction consistently harms the most marginalised first. It forces Indigenous Peoples from ancestral lands, robs small island states of territory, pollutes the water sources of low-income communities, and erodes the livelihoods of those least able to adapt. People disempowered through structures of race, gender, ability, or otherwise, find themselves hardest hit by the ecological crisis. As Alpi Nangia’s testimony shows, the loss of crops like yam is not only about hunger but also about culture, ceremony, and spirit—dimensions of human dignity that the law must protect.

Seen through a human rights approach, it becomes clear: ecocide is not only an environmental imperative, it is a human rights imperative.

The law evolves in response to history’s lessons

After the horrors of the Second World War, humanity declared that crimes like genocide and crimes against humanity must be punished as offences against all. Today, the devastation of our planet presents an equally urgent challenge.

If international law could adapt then, it must adapt again now. The recognition of ecocide as an international crime would affirm what communities on the frontlines already know: that protecting the natural world is inseparable from protecting human life and dignity. From the yams of Yakel in Vanuatu to the forests of the Congo Basin, the message is the same: survival depends on justice for the Earth itself.

The missing crime is ecocide. To fill that gap is to safeguard not only our environment, but the very foundations of justice, equality, and survival.

This is an opinion piece by Kate Mackintosh.

Kate Mackintosh is Executive Director of UCLA Law Promise Institute Europe. She has worked in human rights, international criminal justice, and the protection of civilians for three decades, contributing to the development of international criminal law in its early years.