Meeting the climate challenge depends on revising our social architecture.

At this year’s Luxembourg Sustainability Forum, the atmosphere oscillated between sober realism and tentative hope. The enthusiasm of the Paris Agreement era has visibly eroded, replaced by a “sustainability backlash” where political zigzagging feels like a permanent state of one step forward, two steps back. Yet, amidst this collective disillusionment, a different narrative emerged from the stage. The speakers did not offer a checklist of technical fixes; instead, they engaged in a high-level dialogue about a fundamental restructuring of how human beings imagine, organise, and trust one another.

The central tension of the day was linguistic and conceptual. A consensus quickly formed that the term “crisis” is no longer fit for purpose. Mathieu Baudin, a historian, futurist and director of the Institut des Futurs Souhaitables (IFs), shed light on this shift by arguing that a crisis is, by definition, a temporary fever that breaks. “Fourty years of crisis is too much for a crisis; it is a metamorphosis,” he observed.

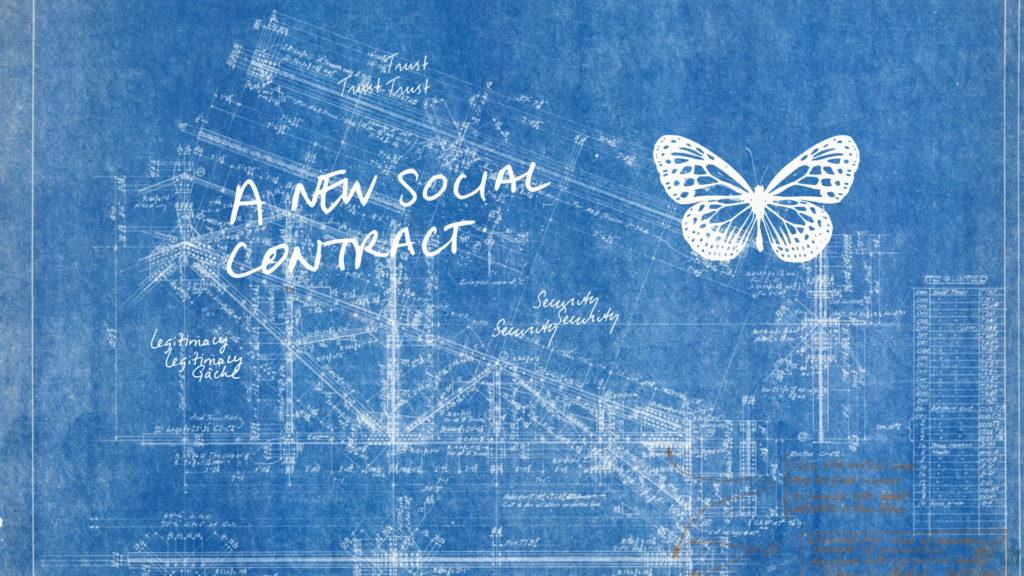

Drawing on Antonio Gramsci’s concept of the interregnum, a time when the old world is dying but the new one has not yet been named, Baudin posited that we are living through a “state change” rather than a mere disruption. Using the biological analogy of a caterpillar dissolving within a cocoon to become a butterfly, the historian suggested that our current “passive acceptance” is a symptom of this dissolution. Baudin’s conclusion: Our current lifestyle is “no longer in stock,” and the material transformability of human civilisation is inextricably bound to the plasticity of our imagination.

“Fourty years of crisis is too much for a crisis; it is a metamorphosis,”

However, a distinct nuance emerged from the contributions of Clover Hogan, a prominent climate activist and founder of Force of Nature. While agreeing on the magnitude of the shift, she pivoted the focus from biology to politics, arguing that the paralysis is not due to a lack of technical know-how or just a failure of imagination, rather a “crisis of power” maintained by myths of individualism and the cynical belief that the status quo is incapable of change.

Here, the dialogue between speakers crystallised a critical insight: We have the technology (Hover) and the historical imperative (Baudin), but we lack the social architecture to bridge them.

The silence of the majority

François Gemenne, IPCC co-author and environmental geopolitics expert, deepened this political critique by dismantling the excuse of scarcity. “The most important message is not a number, but an affirmation,” he stated. “We possess all the knowledge, all the technologies, and all the financial means to keep the Paris objective.” If the means exist, why the paralysis?

Gemenne described the phenomenon of “green-hushing.” Because companies receive no clear signals from wavering governments, they have moved from green-washing (deceptive noise) to green-hushing (strategic silence). “Communicating on climate has become shameful,” Gemenne noted, “because there is the public perception that no one is doing anything.”

Because companies receive no clear signals from wavering governments, they have moved from green-washing (deceptive noise) to green-hushing (strategic silence)

This silence creates a distorted reality. Gemenne cited social psychology to explain a “spiral of silence.” While only 10-15% of the population actively opposes the transition, this “noisy minority” dominates the discourse. The majority, believing themselves to be the minority, hide their views, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of inaction. To break this spiral, Gemenne argued we must correct three distinct behavioral errors.

The first is characterised by communicative failure, where we persistently frame the transition as a sacrifice of immediate interests for an abstract “other,” clashing with economic structures built on self-interest. Secondly, lapsing into moral judgement—which breeds defensiveness—marks a stark deficit of empathy. We ought to move away from shaming to valorising “good reflexes.” Lastly, overwhelmed by complexity, society retreats into nostalgia—flight into the past. We must stop viewing the future as a hostile collapse and, instead, project ourselves into it with agency.

If Gemenne diagnosed society’s silence and behavioral incoherence, Hugo Paul, a “community explorer” who was previously engaged in the Génération Climat, offered the architectural repair. Highlighting a “crisis of us” as evidenced by plummeting empathy levels and rising loneliness, Paul argued that climate change requires the highest level of human cooperation in history, precisely at the moment when our capacity to cooperate is at its lowest.

To counter the “flight into the past,” Paul proposed an anthropological roadmap derived from resilient communities. The dialogue centered on three central pillars for this new social contract: the architecture of a new “us.”

3 Pillars of a

New Social Contract

Trust

Baudin described trust as both the remedy and poison of our age.

Rising polarisation, as sociologist Aladin El-Mafaalani notes, stems less from disagreement over issues than from divides in whom people trust. Some trust governments, others trust those who distrust authority.

Paul adds that genuine trust cannot be mass-produced—it must be nurtured in small personal connections and then scaled.

Security

Citing neuroscience, Paul highlighted that a brain under threat cannot cooperate; it can only defend.

The proposed paradigm shift is to create social “membranes”: spaces porous enough for exchange but defined enough to offer the psychological safety required to show vulnerability, admit cluelessness, and take risks.

Legitimacy

Addressing the economic anxiety that fuels backlash, the dialogue turned to legitimacy. Drawing on the French trade guild tradition, the concept of the gâche (a recognised role) was introduced.

A successful metamorphosis requires that every person finds a dignified, recognised utility in the new world, countering the narrative of sacrifice identified by Gemenne.

Surviving the Winter

The Forum concluded not with a roadmap of specific policy recommendations, but with a realignment of perspective. There was no dissent on the difficulty of the road ahead: Hogan warned that “each broken promise corrodes trust,” while Baudin acknowledged that “tomorrow looks like an erosion of the present” to many. However, the prevailing sentiment was that this “winter” is a necessary season of contraction, not the end of the story.

The dialogue suggested that while we possess the hardware (technology) to save our habitat, we urgently need to upgrade our software (humanity). Achieving stability, through the deliberate construction of trust, security, and legitimacy, might help us to weather the storm outside. As the session closed, the question lingering in the room was not “Can we fix the climate?” but “Do we have the humanity to save each other?”