Emily Garthwaite is an award-winning photojournalist, writer, and storyteller focusing on environmental and humanitarian stories. Her work weaves together themes of shared humanity, displacement and coexistence with the natural world. She has walked over 1,500km through Iraq, including the Arba’een pilgrimage in Southern Iraq, the world’s largest annual pilgrimage, three times, and walked a 230km thru-hike across the Kurdistan region to document the Zagros Mountain Trail, the region’s first long-distance hiking trail, of which she is a co-founder. Since 2019, Emily has been documenting the Kurdistan region’s mountain traditions and contemporary archives as part of a long-term multi-disciplinary project. In 2020, she walked 200km across the Zagros mountains in Iran to document the nomadic customs of the Bakhtiari tribe. In 2021, Emily and a team of international and Iraqi environmentalists made a 1,900km source-to-sea expedition by boat down the Tigris River through Turkey, Syria and Iraq over three months. In 2023, Emily made a second journey down the Tigris River in Iraq to document the river two years on. Over the course of a wide-ranging conversation, Emily speaks with writer Madeleine Bazil about these long-term projects, reframing narratives, and the radical importance of finding beauty in climate storytelling.

Madeleine Bazil: Could you describe your practice and what your focus is at the moment in your work?

Emily Garthwaite: I initially started working in Iraq because I was fascinated by the country’s surviving culture and heritage and its archaeological sites. I was actually first drawn to the country to walk and photograph Arba’een. Tens of millions of pilgrims yearly travel between the Holy cities of Najaf and Karbala on this pilgrimage. I wanted to photograph the country for everything but conflict, though decades of war are undeniably threaded through every story I’ve focused on. As the work developed and my love for Iraq deepened, looking at culture and heritage through the lens of the environment and climate change became fundamental. Iraq is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world, yet it’s not given the same airtime as other nations struggling with the climate crisis.

MB: Trying to shift people’s understanding of Iraq and of the Iraqi people and of this culture that you’ve come to really love and know—how do you feel environment plays into that?

EG: In terms of climate storytelling in Iraq, to show the urgency of what’s happening in Iraq, the first thing I’m up against is that people don’t know the Tigris River, unlike many other great rivers of the world. So, before I can show you that it’s in a critical state, I need to show what survived in spite of it all and why it’s important. Why is this river important, and why do I want you to care? Iraq is the birthplace of civilisations. Due to a changing climate in Iraq, we have lost places forever. There are many villages in the south of Iraq that people have abandoned. For Iraq, displacement from climate change has already happened and continues to. My quest was for the enduring aspects of the river – the culture and heritage that have survived for millennia. I have experienced the beauty and depth of history but also seen the impact of past decades of conflict and the environmental and geopolitical threats that have left the birthplace of civilisation at risk of becoming uninhabitable to the 30 million people living in the Tigris watershed.

It’s about showing that all is not lost. If we can preserve this river, we’re keeping a huge part of our humanity. If the Tigris River were to die, what would that mean for our shared humanity? If it’s where Abrahamic faiths were first born and where life just began…

MB: Can you tell me more about the Tigris work that you’ve done?

EG: In 2019, writer Leon McCarron told me of his dream to follow the Tigris River from source to sea by boat. It seemed an impossible feat, but I was in love and living in Iraq, and I said I would join. Two years of planning and logistics later, in 2021, we made a 1,900km three-month source-to-sea journey through Turkey, Syria, and Iraq using multiple boats alongside a team of regional environmental defenders. We were seeking out these stories of survival, whether it was character-led, archaeological, or environmental. We worked with prominent environmental defenders, including Salman Khairalla, Co-Founder and CEO at Humat Dijlah [Save the Tigris]. For us, it was essential that this be a community practice. It was the first time Salman had seen the Tigris in its entirety in Iraq. This was an opportunity for Iraqis to have this experience as well—this was so important. What I really wanted to do was to inject the organisation with some new imagery, for example, of the archaeological sites, of the wildlife that survives, and the communities that are finding solutions because we must have this balance in climate storytelling.

I also make this work to try and keep myself afloat about the global climate situation. If I’m only going to these disaster sites, I won’t have the energy to continue because it makes me so sad.

MB: Completely. You need more of a long-term narrative of something other than just climate disaster to keep you afloat on this sort of thing.

EG: Yeah. After the expedition, I spent a couple of years continually returning to different points along the river across Iraq, witnessing the changes, joy, beauty and devastation across all four seasons. I worked on assignments focusing on environmentalists in the marshlands, changemakers in Basra, the survival of green spaces in Baghdad and post-conflict Mosul. And then, in 2023, when my relationship ended, I decided to follow the river again for a month with my friend Sangar Khaleel, and from there, the story Tears of the Tigris was formed. It was a slower journey, and it allowed me time for conversations on riverbanks and time to develop a richer understanding of the folklore and sentimentality that local communities feel towards the Tigris River.

I just wanted to sit on riverbanks with Iraqi people and connect with their love for the Tigris, their romantic notions of it, and the folklore, stories, and poetry that live along the river. You know, what sustains people. The work has moved from survival to what sustains people.

I just wanted to sit on riverbanks with Iraqi people and connect with their love for the Tigris, their romantic notions of it, and the folklore, stories, and poetry that live along the river. You know, what sustains people. The work has moved from survival to what sustains people. We would often stay in a village for 2 or 3 days, attend birthday parties or weddings, family picnics, and afternoons spent gardening or repairing fishing nets. I found that the people I’d return to, and many I’d already visited at least 3 or 4 times over the years, had seen a significant change in their environment. I took so few photos on my second journey down the Tigris river. Instead, I listened to people, trying to absorb and get a sense of how people are bound to that river in the most beautiful ways. People, when you speak to them about the river, they speak from the heart. They speak in a very, very spiritual way. The river brings out their truest self.

I also dug deep into the sites of environmental destruction and returned to the points I’d visited in 2021. I have been making this work for history, too. As it stands today, the river is not going to survive. In decades to come, monumental shifts will be required for life to sustain along the river.

MB: I wanted to ask about the Zagros Mountain Trail that you helped develop. I’m keen to hear about what that experience has been like, and the work that’s come out of it.

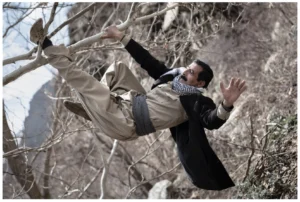

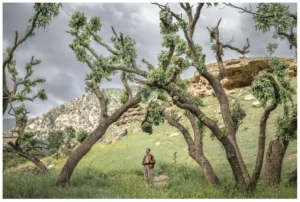

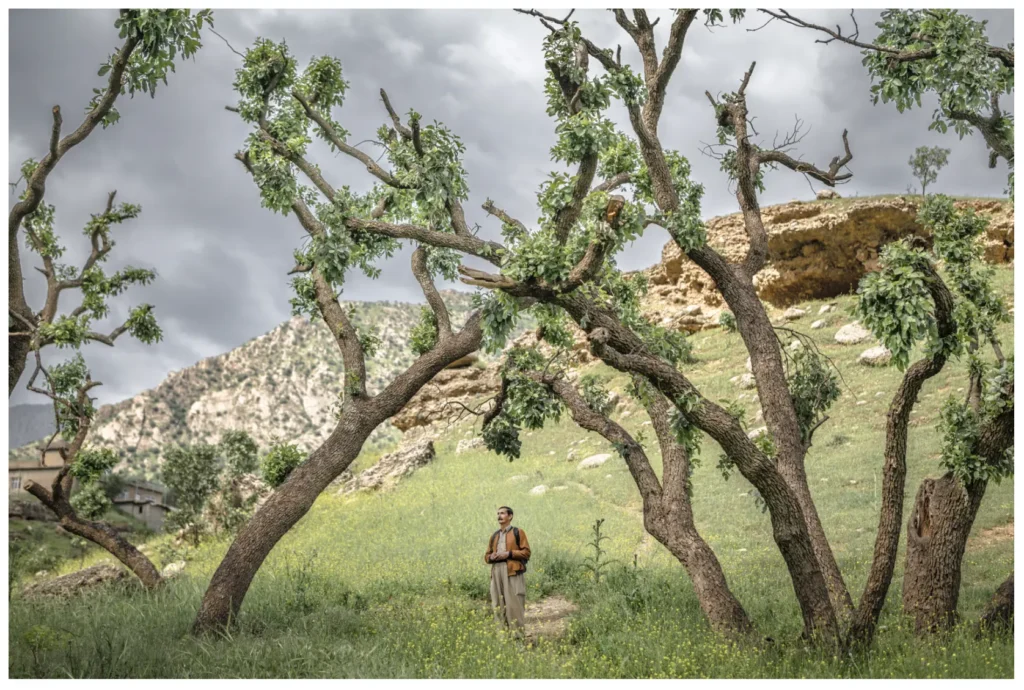

EG: The Zagros Mountain Trail is Iraq’s first long-distance hiking trail in the Kurdistan Region. Leon McCarron and Lawin Mohammad introduced me to the project in 2019. This was my first introduction to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. We’ve since walked thousands of kilometres, testing out different routes, finding old trail pathways and working with local communities and guides. One of the best ways to understand and explore a country is on foot. All we did was work on stitching pathways together; old shepherds’ routes, old militarized roads, pilgrim ways. The trail doesn’t belong to anyone, but it can only succeed and be nurtured with cross-collaboration and a shared vision, which we found as we developed relationships with local stakeholders. Now, it’s 136 miles long with 14 stages and a network of homestays and local guides. Now, the trail is creating a life of its own.

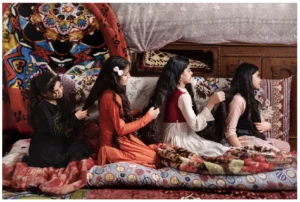

My photography practice began simply documenting the trail’s creation and then developed into a more archival-based project. I have been trying to find things that have survived since the Kurdish population went through the genocide. Most people had to leave everything behind. So I’ve scanned old photographs, photographing marital rugs, even seeds. Very few objects have survived. It’s been a project that I’ve been working on since 2019. I would turn up in a village on foot and say: ’What have you got? Do you know anyone who’s got any old photos? Do you know any medicine women who are still working? Do you have any objects in your home that are from the ‘70s, ‘60s, or earlier? Any old books?’ And, in most cases, the answer was no. It’s slow work and very challenging.

MB: The nice thing about a long-term project that’s meandering its way forward is that you have that space to reach that point, and let your understanding of it evolve. Do you feel like there’s any particular role or responsibility for the storyteller – in whatever medium – to create work in any particular way? Or any kind of responsibility, in this current climate moment of crisis and collapse, and all the intersecting social and political ways that that manifests as well – do you feel any particular pull to do something in particular with your work?

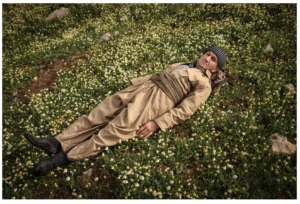

Finding and documenting beauty. That’s become such a priority. It can feel harder and harder to find, and so the pursuit of beauty has become this challenge… Beauty can be in the light or the glint in someone’s eye, the story, the poetry, or whatever it might be. Ultimately, it’s only my perception of beauty. But pursuing that and seeking that out has become the most urgent thing for me.

EG: Finding and documenting beauty. That’s become such a priority. It can feel harder and harder to find, and so the pursuit of beauty has become this challenge… Beauty can be in the light or the glint in someone’s eye, the story, the poetry, or whatever it might be. Ultimately, it’s only my perception of beauty. But pursuing that and seeking that out has become the most urgent thing for me. I think I’ve realised it’s the quickest way to people’s hearts and minds and to get their attention. When looking at environmental and climate storytelling, images of disaster often differ from what the general public is willing to consume because they turn away very quickly, so when I’ve been trying to get people interested in Iraq, whether, within climate, environment, culture, or heritage, it’s been about the pursuit of beauty, which will always pull people into urgent stories.

Artists have always responded best in times of crisis. That’s when the most extraordinary work is often made because it’s a time of urgency and rawness, and perhaps the audience is more willing to digest it. People have flinched at Iraq for so long, so showing beauty feels like the most radical act. I’ve been worried that people will think it’s a naive thing?

MB: I don’t think that’s naive at all. I’m a poet, and something that I think about often is how much poetry exists – and I think this stands more broadly for just art in general – about loss and heartbreak and devastation. And that’s seen as serious work. You make work that engages with that, and people are like, ‘oh, that’s really rigorous and serious and important’. And then you make art about joy and love and beauty, and it’s often seen as fundamentally unserious. And I just reject that. I don’t think that’s the case.

EG: Yeah, 100%. Some of my favourite images have come from perfect, unexceptional days along the Tigris River. I see so much beauty in the mundane. We see so much suffering and pain, but I know, because I see it, that love is the more powerful force. And so, I always turn to the light.

Artists have always responded best in times of crisis. That’s when the most extraordinary work is often made because it’s a time of urgency and rawness, and perhaps the audience is more willing to digest it. People have flinched at Iraq for so long, so showing beauty feels like the most radical act. I’ve been worried that people will think it’s a naive thing?