Photographer Aziziah Aprilya documents the impacts of industrial nickel smelting on families in South Sulawesi’s Pa’jukukang subdistrict, Indonesia.

As a teenager, Hasiah, often visited her grandfather’s farm in Papanloe Village, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. On the two hectares of land, she could find, among other fruits and vegetables, mangoes, apples, long beans, corn, tamarind, and kapok. In the gardens with her cousins, she would pick cassava, and they would rush home eagerly to fry the sweet fruit. At the time, Hasiah lived in another sub-district and only occasionally came to Papanloe to collect produce. In Papanloe, food was always nearby. Many local people worked as farmers and fishermen who rarely went to the market. When it was time to cook, they picked from their own yards and the vibrant gardens of their neighbors. Hasiah moved to Papanloe in 2012. Little did she know that decades later, that the gardens would be replaced and the community would be drastically impacted by industrial nickel smelting in the subdistrict.

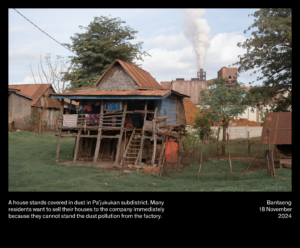

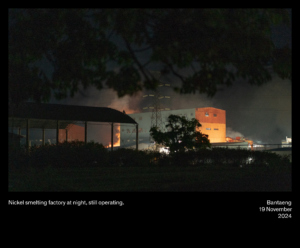

In 2013, Pa’jukukang Subdistrict was included in the Kawasan Industri Bantaeng (KIBA), or Bantaeng Industrial Area: one of the National Strategic Projects (PSN) initiated by Indonesia’s seventh president, Joko Widodo. KIBA was initially introduced as an area to process agricultural and fishery products from Bantaeng residents. But in the same year, a nickel company entered the area and began measuring the land. Together with the government, the company encouraged residents to sell their land for the development of the industrial area. After inheriting her grandfather’s land, Hasiah was able to build a house from the proceeds of selling the land to the Huadi Nickel Alloy factory. And, when the smelting plant began operating in 2019, immense amounts of dust began to disturb the lives of Hasiah and other Pa’jukukang residents.

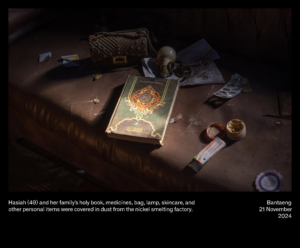

In October 2024, Hasiah traveled away from her home for one month. When she returned, she upper part of her stilt house was almost entirely covered in a thick layer – 2 to 3 centimeters – of terracotta-colored dust. The zinc roof of her house began to corrode and from those holes, dust entered her home: settling on chairs, beds, cabinets, and even the clothes in the closet. Hasiah, and her children, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren have all moved to live only in the lower part of her house.

“I have to sweep and mop many times every day,” said Hasiah in the kitchen that she has moved to the bottom of her house.

Everyday, underneath the house, Hasiah and her daughter-in-law construct bricks that they sell to earn money for their daily needs. She plans to move out of Papanloe soon, although she doesn’t know what she will do when she moves out.

“I was told to move by my family because I was embarrassed when they came here,” she says, resigned.

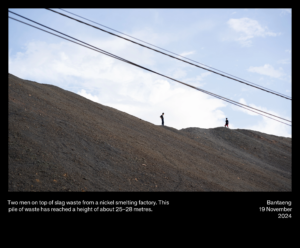

A few meters from Hasiah’s house, a pile of slag – a by-product of smelting metals – sits behind the factory’s concrete fence. The blackish-gray solid waste is estimated to have reached a height of about 25-28 meters. According to a report by the local environmental organisation, Balang Institute, who measured the waste using Google Earth satellite imagery, the slag pile reached an area of approximately 9 hectares in December 2022. With six smelting factories at the KIBA site operating 24/7, it’s unsurprising that the waste has accumulated at such a scale.

I smell the strong odor of sulfur. Occasionally there are beads of water that fall like raindrops. It stings when it hits my eyes.

Some of the residents said that when the new factory came in, many of them didn’t know what kind of environmental consequences they would experience, what kind of air they would breathe.

From a distance, I stare at two teenage boys playing on top of the slag mountain. I don’t know how they got to the top.

Aziziah Aprilya

Like the majority of the women in Pa’jukukang, Yeni is a brick maker. After the industrial scale factories were established, brickmaking processes using soil were slowed due to reduced water flow. “The factory absorbed all the groundwater. The well dried up,” said Yeni. After the residents took action, the factory finally built a 300-meter long pipe to drain the water needed by the residents.

“Every time we wash, the first wash water is brown,” says Sana, Yeni’s niece.

In 2023, Sana’s husband began working as an excavator driver at the factory, earning around 5 million rupiah a month. But with children, grandchildren, and her mother to support, Sana still needs to earn extra income. She continues making bricks at Rp100 each, producing about 5,000 a month for Rp500,000. Each day, Sana and Yeni work from 8 to 10 a.m., break for lunch, then resume from 2 to 5 p.m. Sumiati, her 16-year-old granddaughter. For years, Sumiati – Yeni’s 16-year-old granddaughter – has helped to mold the bricks.

After her divorce, Yeni returned to Bantaeng with her one-year-old daughter. “I want to move. I plan to buy land in Kesi-kesi,” said Yeni, who hopes to start cultivating rice fields elsewhere in Bantaeng. Her eldest child is waiting on a promised job offer from the factory, which came after he sold his land. He previously worked in Malaysia on a palm oil plantation.

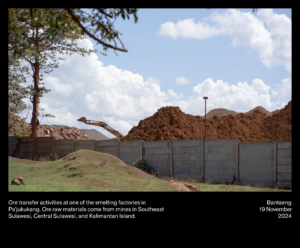

Yeni’s house shares a wall with PT Hengsheng New Energy Material Indonesia (HNEMI). From her backyard, yellow excavators are visible transporting raw materials from mines in Southeast Sulawesi, Central Sulawesi, and Kalimantan. Indonesia holds the world’s largest nickel reserves – many of them in Eastern Indonesia. The semi-processed nickel is exported internationally.

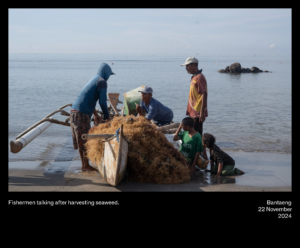

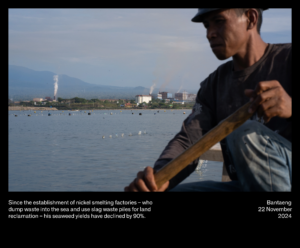

The nickel smelting project in Bantaeng spans 3,252 hectares – 3,151 hectares of land across six villages and 101 hectares of coastal waters slated for reclamation. This coastline in Pa’jukukang was once a thriving seaweed farming area. But now, factory waste and land reclamation have degraded the marine environment, making it difficult for seaweed to grow.

“We used to be able to harvest one ton [a year], but now we can only harvest 100 kilograms,” said Jusman, a seaweed farmer.

The extractive operations of the nickel industry have impacted not only Jusman, Yeni, and Hasiah, but many others in Pa’jukukang. By 2023, the Indonesian government had issued 373 nickel mining concessions. This industrial expansion has cleared nearly 80,000 hectares of forest, threatening ecosystems and dismantling local livelihoods. Residents are left struggling for clean water, breathable air, and healthy soil. And they are forced to face a painful dilemma: leave everything behind, or stay and bear the consequences.

Full photo story with captions: