If ever there was a threshold for the climate crisis it was passed long ago. The fallout of massive supply chains, along with ceaseless exploitation of natural resources has long been cruelly unseen, suppressed or simply unmentioned in those swathes of the world that have been underrepresented in global discourse. In contrast, COVID-19 pandemic, has been a highly publicised and nearly inescapable. A most traumatising and devastating case study for how the many growth-dependent infrastructures of nations globally will respond to an increasingly volatile habitat.

In a matter of months the social landscape has changed, countless people and communities are precariously positioned for an uncertain future, while only the industrial behemoths of wealthy nations thrive. The crisis that global industries have sown cannot be evaded, yet designers have long been modelling what ecological production can look like, while also creating supply and materials that more likely to be regenerative when disaster inevitably strikes.

In the almost twenty years since the publishing of the seminal design manifesto Cradle to Cradle, which popularized the idea of circular economy into the design discourse, designers have been striving to bring ecological design into common practice. Finding alternative biomaterials, limiting production and creating open-source networks for ecological design strategies. Even as recycling and waste infrastructures of the wealthiest nations remain shockingly ineffectual, major industries extend their supply chains ever further across the earth, and reliance of fossil-fuels remains ubiquitous, many design studios are determined to seed ecological production as a viable and indeed resilient alternative to the mass consumerism that has reigned supreme. In this potent time, as the increasingly visceral realities of the climate crisis and now COVID-19 provide more detailed glimpses of the more commonplace chaos that the climate crisis and mass extinction will bring, the future of design is necessarily ecological and is being born from design practices around the world.

Photography Jonas Lindström

“It’s clear we aren’t moving fast enough.” Says Allon Lieberman, design manager speaking for the studio Form Us With Love (FUWL). For the Stockholm-based design studio that has long sought holistic solutions in their design projects “there are always challenges to implement better materials, or advocate for leaner shipping. But in reality, the problem is greater than form giving.”

More than creating the product, addressing the economic models that enable something to be produced—to exist, are a necessity to producing design that exists harmoniously within an ecosystem.

FUWL demonstrated this idea comprehensively with a project recently kickstarted called FORGO a liquid soap product that rethinks how the commonplace is produced, packaged, and transported. Prior to the pandemic, liquid soap might seem an unassuming choice for an ecological redesign but now the importance of access to hygienic products is not taken for granted. FUWL built off of the absurd fact that most liquid soap products are basically just water in a single-use plastic dispenser. By using a reusable dispenser, and “just add water” powder (in a little recyclable pouch) FORGO created a soap that cuts down on the carbon footprint of such products by 92%. “We found the factories and defined the economic model behind the product so we didn’t need to compromise where we weren’t comfortable to do so.” Says Lieberman, “Our ambition as a studio to design real change [let] ideas like FORGO come to life, and with relatively little resources.”

With FORGO FUWL stretched the boundaries of where design begins and ends, yet not without including the many other collaborators and experts that made FORGO possible. In designing for an ecosystem, the designer has to rely on collaborators in other disciplines to avoid unintended impact but they must also educate themselves. “the designer’s responsibility to consider the impact, do their part to reduce it, and educate themselves and others.” Write Jonny Black and Richard Roche of Cast Iron Design (CID). Producing sustainable branding in Boulder, Colorado, the duo creates an open-source material profile for every project in their portfolio—creating case studies and seeking solutions whenever they cannot find material that is reasonably degradable. Even having implemented the world’s “First Algae offset ink” —created by biomaterial company Living Ink—in a print project for outdoor-brand Patagonia. “By inquiring about more sustainable options, even if they do not coalesce for the project in question, a designer is creating demand for that product.” Says the team. The studio has solidified their “sustainable design” practice in their commitment to low impact materials and ecological ethics—which has built them a community of clients devoted to CID’s production principles.

Which isn’t a surprise as plastic in particular has provided a traumatic demonstration of how careless materialism can impact our habitat.

While it might seem like industries have been wising up to the ills of the plastic crisis, it is notable that most of the plastic that exists in the world today was created in the last decade. As demand for fossil fuel declines due to the growing market for alternative energy, oil companies are shifting their focus towards making more plastic.

It is estimated that global plastic production will double over the course of the next 15 years. Making the need for alternative production methodologies, that avoid these fossil fuel derived plastics, all the more urgent.

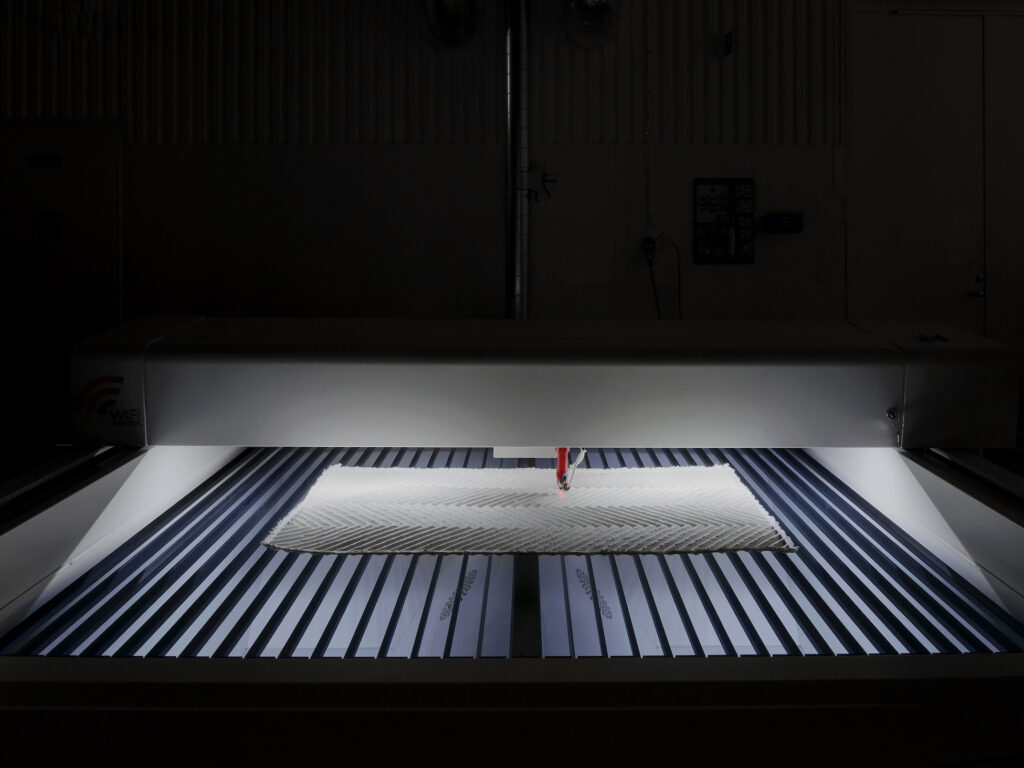

In order to deviate from this upsetting projection—algae along with the fungal mycelium, as well as chitin are increasingly being applied as alternatives in material design production. In architecture, cross-laminated timber has gained popularity as replacement for the carbon-intensive materials in the construction industry—which is estimated to produce over 40-percent of global carbon emissions. More than simply replacing the caustic materials like plastic, steel, and concrete, many of these biomaterials are doubly beneficial for their carbon-negative impact, offering the opportunity to make clothing, buildings, furniture, packaging and all manner of design products carbon-eating. Much of the success of biomaterial fabrication is in large part thanks to the growing success of foundries like Ecovative Design. Foundries and material research organizations around the world have made accessing these malleable materials easier and have provided open-sourced production methodologies that have made the ability for designers, who are perhaps uneducated in using biomaterials, to quickly educate themselves in ecological production.

Photography Jonas Lindström

Beyond the material of the products being created, serious reexamination of how producers and consumers characterise products, has become a necessary part of new ecological design. “We believe that imperfection is perfection” says Hsin-Ying Ho of the Berlin-based design practice Yellow Nose Studio. In the process of designing their wares Ying and collaborator Kai-Ming Tung, instill the objects a character that is otherwise lost in mass production practices. While the frictionless and characterless commodity—think the featureless and monolithic smartphone, the unblemished glass skyscraper, the unspoiled Helvetica—is often positioned as the ideal of modernity. A product without character is ultimately replaceable, and is likely designed to be replaced, yet when the material and manufacturing bring about something original and storied, it transcends commodity. For the products of Yellow Nose Studio, it is their individuality, the narrative of their handmade production that gives them value, rather than taking away from it, “letting the materials speak of themselves is the center of the idea when it comes to creating.” Says Ying, “We believe that showing and preserving the marks and the reflections of their own are the emotions that we are lacking in this fast paced innovative era.”

Ying and Kai’s collections are meant to reflect “slow living” —a retort to the fast consumerism that has ensured excessive consumption of energy and resources. “You learn what you need and what you want from the space you live, the environment you are in.” Says Ying of the way that an object in an ecosystem must reflect the user and the user’s environment. It is not enough that the material and means of production are remade, but the way that a product is designed to be used and understood must change.

The relationship between production and consumption, can only ever become circular if both parts of that process are mindful of the system that has never been without its limits. Burning through products, just as burning through fossil-fuel inevitably will end in waste and ruin.

Mitigating the continued loss of natural resources, the worsening climate crisis, and species lost are a necessity but as so much has been done already, we cannot simply hope to “fix” things overnight, or even over a decade or two. The damage is done, and nature cannot be escaped—pandemic, or rising seas, droughts or fires, these things will always impact infrastructure and the systems that we design.

The methodologies that designers are creating and sharing, are not only working to eliminate the wasteful and carbon-exuberant practices that have defined industry, but they are also creating the new economic models that are more resilient to the inevitable crises many geographies will continue to confront.

Yet they remain in the minority. The supply chains that bring us mass produced products, that are often recklessly regarded as infallible, are strong only in the sense that they are domineering and tyrannical. They continue to stock the furniture fairs and superstores and the wealth that powers those long lines of production continue to use whatever means necessary to bend nature and people towards a process of rigid production. For the many that must inevitably escape theses destructive strictures and create more adaptive economies in an increasingly chaotic environment, futures lie in new ecological economies. Designers—deliberately and often obsessively—are working to build the models for those futures.