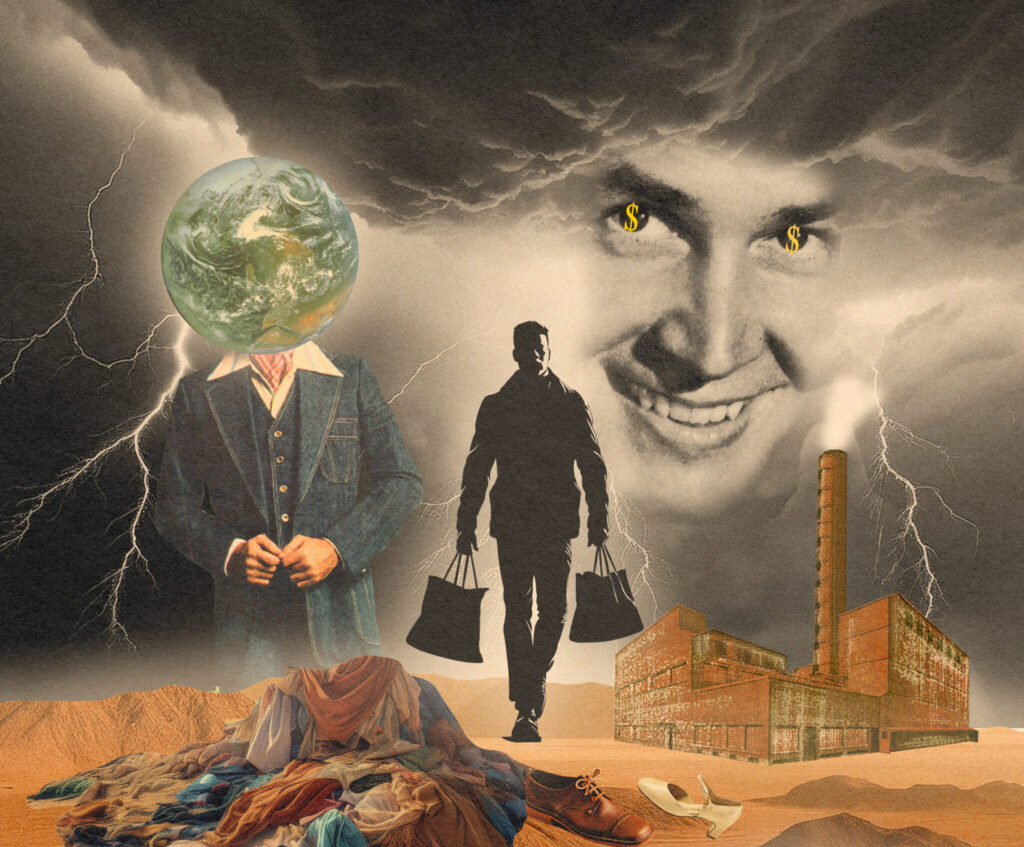

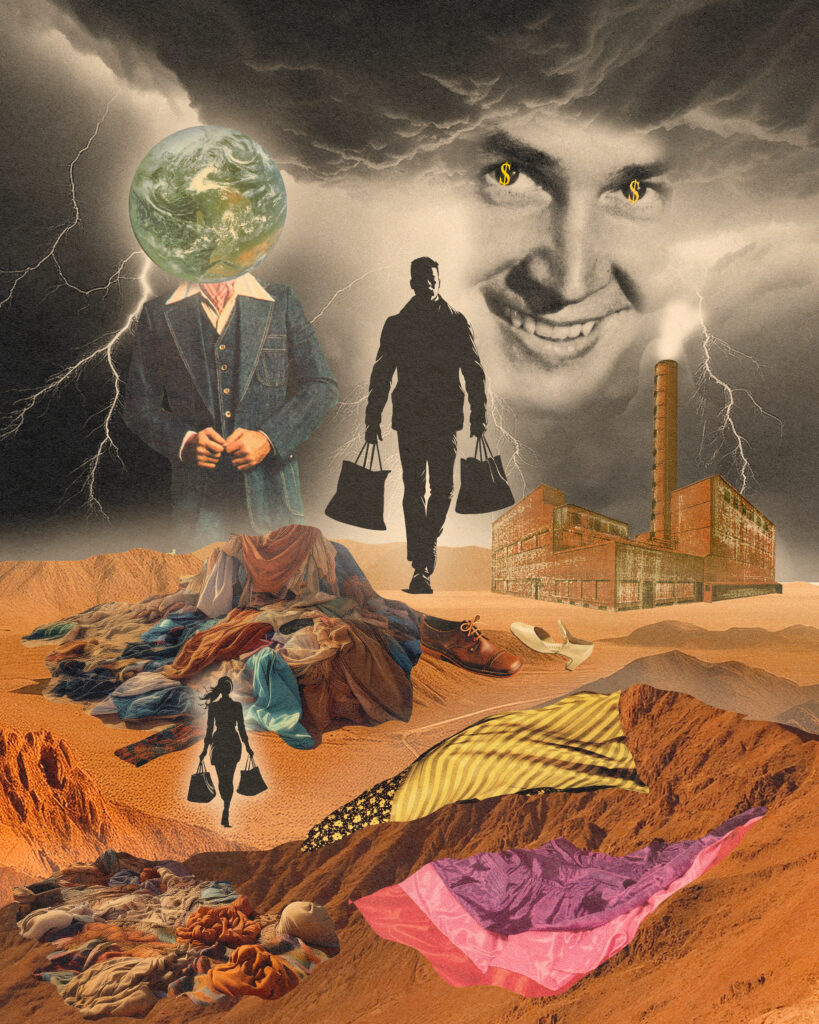

How the massification of luxury fashion led to the industry’s waste problem

We are at a critical point of material excess in the fashion industry. Although most brands still fail to disclose their production figures, it is estimated that there are 100 to 150 billion garments produced annually and 92 million tons of clothing ends up in landfills. The fashion industry’s overproduction practice is rapidly depleting our natural resources. The industry is the second largest consumer of water and is responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions. The industry’s waste, made up of unsold and discarded garments, textiles and accessories, is piling up, smothering areas of our planet like the Atacama Desert in Chile and the coast of Ghana. While there is still beauty and creativity to be found in fashion today, the industry has undergone a seismic shift over the past few decades, and the rise of conglomerates, middle market expansion, and the relentless growth of fast fashion has fundamentally changed it. What began as an effort to democratize luxury and maximize profitability has spiraled into a vicious cycle of waste creation in the forms of brand’s overproduction and consumer’s overconsumption habits ending in environmental degradation.

Clothing has existed since ancient times, both as a necessity and a luxury item made of the finest materials. The industry and luxury houses we still have, date back to the late 19th and early 20th century. Hermès and Louis Vuitton are the oldest surviving luxury brands, both founded by artisans who perfected their craft in making harnesses for horse riding and steamer trunks respectively. Lanvin and Chanel followed, both opening millinery shops as their first business. Luxury houses catered to the wealthy elite and were synonymous with craftsmanship, quality, creativity and exclusivity.

Post World War II, luxury began slowly expanding globally, spurred by rising economic prosperity and the allure of beautiful craftsmanship and exclusivity. Luxury houses remained one-man, or family run businesses during this initial growth. Profit was a goal of course, but designers were driven also by their desire to make the finest quality garment one could have. Licensing did change the game a bit, Christian Dior began to license his name for use on accessories like hosiery to extend business with the production cost in the 1950’s. Pierre Cardin followed suit, as did Yves Saint Laurent with his lower priced “Rive Gauche” Line in 1966.

The 1960s through the 1980’s the industry saw a growing appetite for European luxury brands globally. Houses like Gucci and Louis Vuitton expanded into key international markets such as Japan. They gained new visibility through fashion weeks and media and began to advertise in earnest. This set the stage for the globalization and corporatization of the luxury fashion industry.

In 1987, Louis Vuitton merged with Moet Hennessy, forming LVMH. The years following in the 1990’s and into the 2000’s consisted of a cut-throat game of acquisitions and trading of company shares that resulted in the formation of luxury conglomerates LVMH, Kering, and Richemont among others. The mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity continues today. In 2022, there were 292 M&A deals struck in the global fashion and luxury goods industry. The number marked the highest M&A activity observed over the past five years.

The leaders of this transformation were a new generation of CEOs with business backgrounds who were driven by profitability, scalability, and global market penetration. Bernard Arnault, who became chairman of LVMH in 1989 made his intentions clear, “the luxury goods industry is the only area in which it is possible to make luxury margins”. They poured money into advertising and started to shift the marketing focus from the intrinsic quality of the product to its symbolic and emotional resonance with consumers. Luxury products signaled a lifestyle of status and success.

Growth was the goal for brands in the 1990’s and 2000’s and the burgeoning middle class, who was eager to show its status, made it the most desirable market for brand expansion. CEOs brought in new designers such as Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton and John Galliano at Christian Dior who received massive press, hype and attracted a new generation of customers to the store. Brands expanded retail operations and increased their affordable, often logo-covered “entry” products. The strategy worked and sales and profits surged. By enriching products with symbolic and emotional value, brands were able to maintain their allure while catering to a broader market. Luxury, once a marker of elite exclusivity, was slowly transforming into a globally scaled, emotionally charged, and mass-marketed phenomenon.

Luxury’s expansion meant brands increased their offerings beyond the traditional two-season model, adding collections and supplemental lines like swim and lingerie to boost sales. This demand drastically increased designers’ workloads. John Galliano once managed 32 collections across Christian Dior and his own line, while Marc Jacobs handled 16 between Louis Vuitton and his brand. This relentless production is now recognized as a key factor in the creative burnout and high-profile resignations that have characterized the industry as of late.

The rapid growth of luxury also fed directly into the growth of fast fashion and contributed to its rise. Among luxury’s growth strategies was the idea to produce diffusion lines with a lower price point. Orsola de Castro, co-founder of Esthetica Consulting and the non-profit Fashion Revolution argues that luxury brands played a role in the rise of fast fashion by initially promising to democratize fashion through affordable diffusion lines, but ultimately prioritizing profit, pointing out that “[luxury brands] realized they could make things cheaply in China as fast fashion was already doing successfully, but still make their margins keeping prices only 10% cheaper than the main brands. She asks, “would we have wanted the fast fashion as much if the diffusion lines had done what they were supposed to be doing?”

By attempting to appeal to mass-market consumers with diffusion lines, luxury brands found themselves in direct competition with fast fashion brands like Zara and H&M who were already gaining popularity rapidly with their ability to produce runway imitations at a fraction of the cost without a “secondary” name. Fast fashion’s success did, however, provide an opportunity for luxury house growth that took off in the 2000’s,starting with H&M’s 2004 collaboration with Karl Lagerfeld, which set the stage for a wave of mutually beneficial fast fashion and luxury designer partnerships, effectively bridging the gap between luxury and mass market appeal. Fast fashion brands prioritize speed and affordability. Their business models are built on churning out low-cost, trendy garments at breakneck speed and affordable prices. Zara, often cited as the pioneer of the modern fast fashion model, was founded in 1975 as a small store offering affordable replicas of high fashion but in the 1990’s developed a unique design and distribution model that reduced the time from design to retail, allowing it to respond to emerging fashion trends at record speed. Zara now introduces more than 20 collections per year and twice weekly in stores. Shein, a relative newcomer, reportedly offers as many as 600,000 items for sale at any time with the average price being ten dollars. Fast fashion consumers are lured by the promise of affordable options and endless variety, creating a dopamine hit every time they purchase. This short-term satisfaction feeds a cycle of impulsive buying and discarding, and brands feed this cycle by flooding the market with cheaply made clothing designed to be worn a handful of times before being discarded.

The fast fashion and luxury sectors, though built on vastly different principles and offerings, have become deeply intertwined, fueling a common culture of overproduction, overconsumption and a growing disconnect between consumers and the true lifecycle of their clothing. As more collections were introduced and with fast fashion replicating everything at speed, the market was flooded with products, a huge portion of which went unsold. This overproduction is still going strong. In 2023 alone, the fashion industry produced between 2.5 and 5 billion excess items of clothing, valued at $70–$140 billion.

The fast fashion and luxury sectors, though built on vastly different principles and offerings, have become deeply intertwined, fueling a common culture of overproduction, overconsumption and a growing disconnect between consumers and the true lifecycle of their clothing.

Luxury and fast fashion also both embraced cost-cutting measures that compromised quality and shortened the lifespan of garments. As labor costs rose in the 1990’s, this posed a challenge especially for luxury companies who now had to answer to shareholders who wanted returns and profits. The strategy[1] was to increase sales volume, adding the aforementioned collections and lines and lower costs across all. It was impossible to replicate quality while reducing cost so they began to cut corners to reap profit. Fast fashion’s reliance on cheap synthetics allowed it to produce clothing at record speed and low cost. Luxury brands followed suit, starting to incorporate materials like polyester which cost half as much per kilo as cotton and took shortcuts like thinner linings and weaker threads. “The qualitative drop has been uniform across the industry and that’s 100% the brands fault…. Fast fashion, ultra fast fashion, luxury and fast luxury are all one and the same” says Orsola de Castro.

Between 1975 and 2019 the synthetic market grew ninefold. In 2021 synthetics made up 64% of global textile fibre production. Virgin synthetic fibers are derived from fossil fuels; thus they are not biodegradable and will remain in the landfills where they are currently piling up for centuries.

The need to lower cost and maximize profit margins also led to both luxury and fast fashion outsourcing production to countries with lower labor costs such as China and Bangladesh. Factories, for their part, in order to make ends meet with the brands allotted budget often required minimum orders of large quantities. While fast fashion was transparent about where products were made, some luxury brands sunk to falsely maintaining their artisanal image by importing foreign workers to European production sites and paying them one quarter of local wages as this enabled them to continue to use “Made in Italy” labels while betraying the ethos it represented. This practice continues today, just last year the Wall Street Journal published a piece exposing Dior and Armani for exploiting foreign laborers to produce handbags at a fraction of retail price. According to documents, Dior paid a supplier around $57 to produce a handbag which it sold for around $2,780.

These cost-cutting and exploitive practices are all done in the name of the bottom line. Yet growth continues to be the goal and increasing sales, the method. According to the most recent McKinsey and Business of Fashion’s State of Fashion report: “Executives are continuing to focus on growth in the year ahead. Nearly three out of four fashion leaders are prioritizing sales growth over cost improvements, a slight uptick from the 2024 survey.” This mindset still ties financial success to producing and selling ever-increasing quantities of garments. Until brands can decouple revenue growth from sales volume the waste will continue to pile up in landfills, deserts and oceans.

The potential for a more responsible and profitable industry exists. New legislation is being passed in the European Union that will affect brands everywhere, requiring them to report on the amount and management of excess stock, as well as the origin of textile production, emission throughout their value chains, inclusion of recycled materials, and labor practices among other aspects of their business. Fines for non-compliance are a percentage of revenue.

Brands also lose out on revenue from creating unwanted and unsold merchandise. McKinsey reported that 74% of customers report walking away from online purchases due to the volume of choice. According to a Bain report, at the end of 2023, about 13 percent of all luxury goods were purchased at discount outlet stores. Rather than just using technology to speed up production cycles as fast fashion brands do, AI and hyper personalized shopping experiences can be implemented to obtain more data on purchasing patterns and enable them to alter production volumes to align with consumer demands. Getting the inventory equation right will decrease excess stock, therefore reducing GHG emissions and potentially bringing production costs down. On demand production models where pieces are created specifically for a customer’s needs not only ensure no excess stock but offer a personalized product. which is increasingly rare and covetable.

Some brands have begun to invest in more robust resale and repair services which can potentially generate revenue while also extending the life of garments and keeping them out of landfill. Investing in and signing off-take agreements with textile recycling companies as suppliers in an era when climate change makes crops and virgin material sources unpredictable is a strategy that select brands are embracing as well. Brands have a role to play as well through their marketing in fostering a cultural mindset to shift away from overconsumption patterns and towards buying fewer, higher quality pieces that are ethically made.

When discussing how the industry can change for the better, Orsola de Castro states, “luxury is nothing unless it is 100% traceable, luxury was originally really about creating wellbeing for both the maker and the user”. Restoring this ideal is a worthy goal and it will require a fundamental transformation across multiple dimensions of the industry. As far as reducing fashion’s waste, which directly impacts both maker and user, fashion’s real power lies in reducing the amount of product brands put into the world.

“Luxury is nothing unless it is 100% traceable, luxury was originally really about creating wellbeing for both the maker and the user”

The term degrowth is defined as “an equitable downscaling of production and consumption that increases human well-being and enhances ecological conditions at the local and global level, in the short and long term.” Supporters of degrowth reason that an economy and culture based on eternal growth doesn’t work on a planet with finite resources and industries that are harmful to human survival need to be wound down and reimaged. If the fashion industry continues its current trajectory, by 2050 it would use more than one quarter of the world’s carbon budget. It’s time for the fashion industry to reimagine its future keeping in mind the earth’s limited resources, and rethink its reliance on endless production cycles.