Underpaid and unrecognised, Karachi’s women waste pickers fill in the gaps of inadequate government systems.

The tide pulls back from Hawke’s Bay before sunrise, leaving behind what Karachi discarded the day before: water bottles, shredded bags, bottle caps scattered across wet sand. Nearly nine thousand plastic items accumulate per kilometer here. “Plastics are the dominant item by count,” says Dr. Syeda Nadra Ahmed, a researcher at the National Institute of Oceanography who has conducted field studies to document the waste on this coastline.

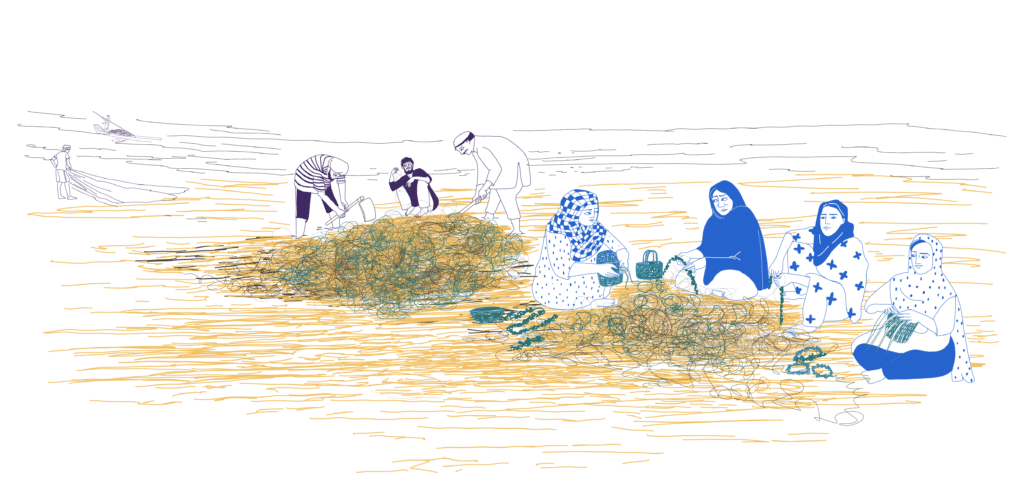

Moving quickly before sunrise, women are already at work here, bent low, filling sacks before anyone notices them. They know what sells and what doesn’t, PET bottles are worth more than film plastic, intact containers more than fragments. Among the usual debris, ghost fishing nets cast off from trawlers working in the Arabian sea lie tangled in dark coils, some buried so deep in sand taking more time to extract. Now they’re breaking down into the same microplastic soup that contaminates every sediment sample from this coast.

Here, women labour daily, and despite the recycling industry depending heavily on their work the municipality recognises none of it. Research shows that these women earn between 300 and 500 rupees per day, and some have worked these beaches for over a decade. They form part of Karachi’s unacknowledged infrastructure, doing work the formal system refuses to. Reaching them directly isn’t easy in Pakistan. Beyond the physical isolation of their work, social norms, family gatekeeping, and the quiet shame of handling waste create a wall of invisibility that keeps these women cut off from the systems meant to protect them. “My experience as a journalist in Pakistan around these communities has been genuinely difficult,” says Aimah Moiz, an environmental entrepreneur.

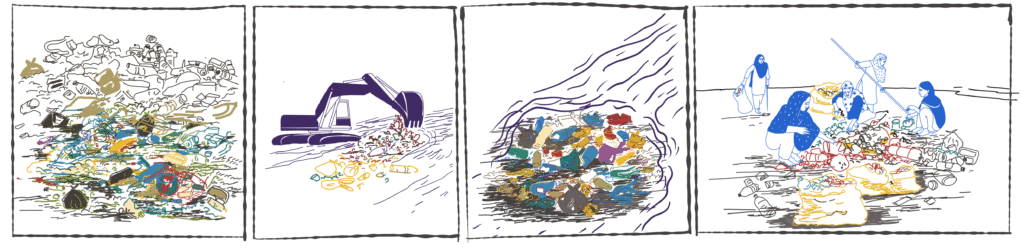

Karachi generates between twelve thousand to sixteen thousand metric tons of waste every day. Formal waste management systems collect roughly sixty percent of it, with the rest accumulating in drainage channels, on street corners, in the ocean. It’s as though the infrastructure was never built to function in the first place.

“When government policies and infrastructure are not able to fulfill the demands, private industries boom up,” says Angela Imadad, CEO of Irverde, a Karachi-based waste management firm. The gap created by municipal failure became a business opportunity. In the 2022-2023 fiscal year, the Sindh government allocated 12 billion rupees for waste management, then requested two billion more from Sindh’s provincial allocations. Nearly ninety percent of that total budget goes to private contractors, many of which are foreign companies, who invoice in US dollars to protect themselves from rupee devaluation. As the payouts rise, drainage systems designed for monsoon water are choked with solid refuse that empties directly into the Arabian Sea.

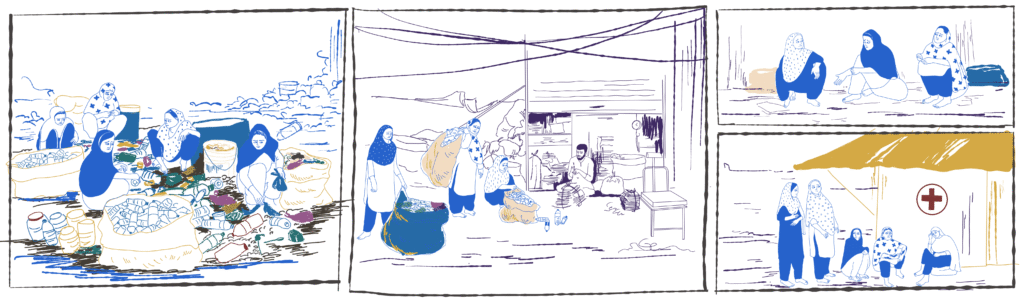

This gap is where women’s labor becomes necessary. While foreign contractors secure dollar-denominated payments for partial services, women waste pickers absorb the deficit; sorting waste, recover materials, and clean up what would otherwise cost the municipality billions. The formal system doesn’t fail despite them; rather, it depends on them never demanding recognition for the work they do, including waste segregation, recovery, recycling – all of which keeps the city running.

In Pakistan, seventy-eight percent of working women, work in the informal economy. In waste, ninety-three percent report exploitation with many juggling dual roles: domestic workers who are also expected to collect recyclables from the same homes with no extra pay. Moreover, cultural restrictions on women’s mobility means they cannot travel to aggregation points or store materials in bulk. Instead, they must make daily sales to the kabariwala – the junk dealer – at whatever price he sets that morning, without the luxury of time to wait for better market conditions.

Surveys and clinic records point to a heavy disease burden among women who sort waste. none of whom receive occupational health and safety training. Eight percent of female waste pickers carry Hepatitis B. and five percent have Hepatitis C. Handling unsorted waste barehanded makes needle-stick injuries a regular occurrence. Studies document elevated mercury exposure linked to irregular menstrual cycles and chronic abdominal pain. At home they manage household waste as well, because in Pakistan, domestic waste management and other household tasks are considered women’s work. The social stigma runs deep. “People are not comfortable telling organisations that they work in the waste sector,” Imadad notes. ‘They’re not happy about it.’

Along the coast, fishing communities have pulled seven tons of ghost nets from the Arabian Sea, nets lost by trawlers, sometimes buried so deep in sand that they take a week to extract. Men do the hauling. Women transform the salvaged nylon into woven products: bracelets, bags, functional goods. Six tons recycled so far, according to Usman Iqbal, who manages the Olive Ridley Project’s coastal work, with orders fulfilled directly to customers – no middlemen extracting margin.

Inland, Nargis Latif runs the Gul Bahao project, converting factory-rejected industrial plastic into modular shelters and furniture. Pakistan’s five thousand factories generate tons of clean plastic waste daily. Latif upcycles it into housing solutions while foreign contractors get twelve billion rupees to haul mixed waste to open dumps. Her innovation addresses waste, housing, and employment simultaneously.

Both initiatives operate at the margins of the city’s waste system. The ghost nets are recovered directly from beaches, while Gul Bahao sources clean industrial rejects from factories rather than household waste. As a result, neither is yet connected to the women collecting mixed waste from streets and shorelines. Iqbal notes that closer coordination could open up opportunities for collaboration over time, particularly if existing informal collection networks were better recognised.

The gap between available solutions and where investment actually goes comes down to policy. One Karachi waste management firm says competition with informal groups is irrelevant because the problem is too big. Investment flows to conventional contracts: collection trucks, landfill management, outsourced operations billed in dollars. Meanwhile, decentralised women-led solutions that function and operate on circular economy principles, struggle for recognition. Scale isn’t the problem and neither is capital. What’s missing is political will to redirect resources toward the people already doing the work.

When China – formerly the world’s largest importer of waste plastics – closed its borders to waste imports in 2018 through its National Sword Policy, it set off a shock to the global waste trade system. Analysts estimate that more than 100 million metric tons of plastic will be displaced by 2030, as exporting countries reroute their waste and increasing volumes are diverted to nations with weaker environmental protections.

Between January and April 2020 alone, Pakistan imported sixty-five thousand tons of plastic waste from Belgium, Canada, Germany, Saudi Arabia. The shipments contained more than recyclable bottles. Documented imports included hospital waste, end-of-life sewerage pipes, contaminated chemical containers, materials that wealthy nations with strict disposal regulations found too expensive or too hazardous to process domestically. Pakistan offered cheap labor and lax enforcement. Women waste pickers, working barehanded, processed this material without knowing its origin or contamination level.

In 1997, Pakistan ratified the Basel Convention, with the aim of preventing the transboundary movement of hazardous waste from rich countries to poor ones. The government drafted a National Hazardous Waste Management Policy in 2022, but enforcement failed and imports continued. “Ocean water acts like a conveyor belt,” said Dr. Nadra Ahmed of NIO. “Litter thrown in one part will eventually be transported to the other side. Your waste will not be your waste – it will cause pollution in the entire ocean” Pakistan is both a source and a receiver, meanwhile it is women as the base of this system who absorb the biological consequences of ratified treaties that have failed to be enforced.

A plethora of solutions exist although implementation doesn’t.

Revise the built environment

Karachi’s drainage system was designed for water, not solid waste. The current sixty-percent coverage of collection waste collection highlights the need for a more expansive door-to-door system. Acknowledging how waste flows into the ocean points to need for greater infrastructural measures: installing trash-traps and river booms at the Lyari and Malir tributaries, the two primary conduits carrying urban waste to the coast, as well as placing screens at stormwater gates. The ban of single use plastics would largely depend on enforcement at scale, rather than token seizures.

Formalise women’s labour

Existing frameworks provide potential entry points to facilitate such formalisation. Pakistan joined the Global Plastic Action Partnership in 2022 and released a Gender Equity and Social Context Assessment later that year. Policy approaches such as Extended Producer Responsibility could strengthen these efforts by placing greater accountability on manufacturers for the full life cycle of their products, to create stable demand and pricing for segregated recyclables. Such measures would enable women to transition from precarious daily kabariwalas sales into contracted suppliers with fixed revenue.

These pathways, however, will succeed only if programmes can reliably reach the women whose labour sustains the system; reporting shows that social and cultural barriers often limit that access.

Initiatives like the World Bank’s PLEASE project – which integrates informal women workers into facilities such as the AltasPak polyethylene plant in Hyderabad – offer glimpses into what scaled formalisation could look like. Furthermore, conditioning all future solid waste management financing, whether from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, or bilateral donors, on meeting verifiable integration targets for women-led cooperatives could advance this approach even farther.

Any effort to formalise this work has to begin with the realities that shape how these women participate in the sector, and with forms of engagement that grow from the conditions they already navigate rather than from structures designed elsewhere.

Protect Health Immediately

Improving conditions for women in the waste sectors also involves basic health protections.

The Sindh Occupational Safety and Health Act, in existence since 2017, provides a legal framework that could guide such efforts. Currently, no surveys indicate women receiving any occupational safety training before entering manholes, handling hospital waste, or breathing microplastic-laden dust. Mandated supportive occupational training, along with the deployment of gender-specific health monitoring for mercury exposure and reproductive impacts could form part of a more comprehensive approach.

Many of these measures are already ratified legal requirements, yet continue to be ignored across the waste-management system. The gap between regulation and practice remains wide.

The women are still there at dawn, working Hawke’s Bay before the heat arrives, carrying out essential labour that absorbs the consequences of systemic failure. As in other places shaped by environmental injustice, it is their bodies that register the effects first.

Pakistan already has the policies to address the waste crisis, and spending patterns show that financing is not the constraint. What remains missing is the political will to redirect investment away from foreign contractors and toward the women whose work underpins effective waste management. Until that shift occurs, the city’s circular economy will continue to operate as circular exploitation presented as environmental action.