Documentary photographer Cat Vinton reflects on her immersive work with nomadic communities living on the frontlines of climate change.

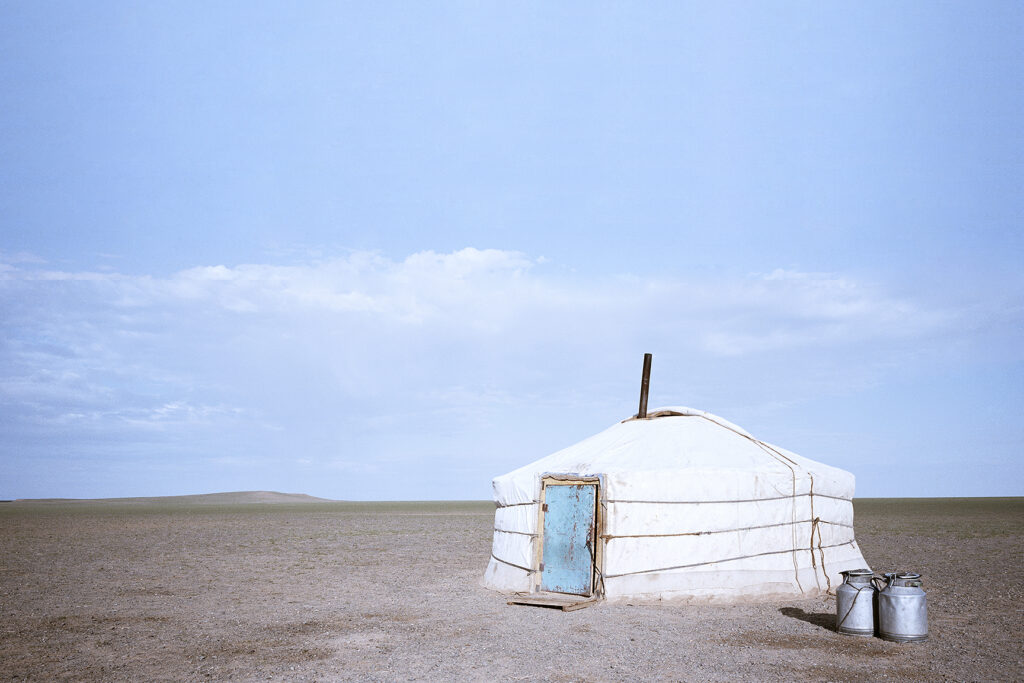

Cat Vinton is an award-winning adventure and ethnographic photographer who has lived amongst and photographed many of the world’s last remaining nomadic communities across the Himalaya, the Tibetan plateau, Mongolia’s Gobi Desert and Altai Mountains, the Arctic tundra and the Andaman Sea. Outside of her Last of the Nomads work, Cat documents artists, activists, filmmakers, explorers, initiatives and organisations worldwide. Cat’s work appears in many books, as well as in National Geographic online, The Guardian, Survival International, Oceanographic Magazine, Sirene Journal, Huck Magazine, Sidetracked Adventure Magazine, and elsewhere. Her body of work, The Last of the Nomads: In Search of Those Who Listen Still, has been exhibited at the Kendal Mountain Festival, Kudhva, and in galleries across London. Icarus Complex’s digital producer, Madeleine Bazil, spoke with Cat about her nomad project, relationship-building, and lessons of climate resiliency.

Madeleine Bazil: Could you tell us about how the Nomad Project began, and how it’s developed over time?

Cat Vinton: My Nomad Project began with a curiosity of another way of knowing the world – drawn to their rugged spirit, their way of life and their lightness of being. Over time I have witnessed their deep connection to land, their sense of belonging to the natural world, their resilience and ability to adapt to change. There’s something fundamental about how they live in relationship with their ancestral lands. Unencumbered by the trappings and comforts of a settled life, they embody a powerful freedom, a force that binds them as communities and underscores their resilience, and it’s this spirit, that I’m drawn to, that I’m trying to listen to and communicate through my images.

I have always been fascinated by the human spirit and our relationship with the natural world. I am dedicated to capturing the stories of lives bound to the land and the sea. To be wild, and free roaming – living in tune with nature’s rhythms – is a way of life honoured by nomadic people for thousands of years. But like the natural world itself, the nomadic way of life is rapidly disappearing. How I’d like to develop the project in more depth is to return with my images to the nomadic communities, building on the trust I have already established and inviting a deeper collaboration to capture their voice and perceptions of the world through other forms of storytelling, to sit alongside my images.

MB: Can you talk about the importance of trust, participation, and relationship-building with the communities you’re working with: what does that look like and mean to you? How do you avoid extractive-ness (or the ’noble savage trope’) when documenting communities ways of life that you’re an outsider to?

CV: Trust, participation, and relationship-building with the communities/families I’m living with, is hugely important to me. I do extensive research on the nomad group I’m hoping to find. Then I print an A2 sheet with loads of images pulled from books or the internet of exactly what I’m looking for. Once I’ve done my research, I know where I’m going, what the landscape is, who the people are, when the seasonal migrations might happen, what kind of homes they live in. And I have that all printed onto a big sheet of paper because it’s something I can have with me, something physical, and it speaks without language.

Then I usually head to the capital of that area – the main town of where there might be a connection to the nomads – and I’ll spend however long it takes trying to meet a girl, a female, just to eliminate those kind of gender complications. And that connection becomes my window into the nomad people. It takes time. Rather than finding a fixer or translator who takes me directly to a family they’ve worked with – who might be more geared toward tourists – for me it needs to be much more empathic.

I don’t take my camera out of my bag for at least a week – I just spend time observing, witnessing, feeling, connecting, smiling – earning their trust. My entire nomad project has evolved through empathy and trust — the connections and friendships I make, and what feels right. This is beyond anything else, the most important part for me. I wait to be invited in and spend deep time with them.

MB: I know you immerse yourself living with nomadic communities. I’d love to hear more about that, and what your creative process looks like.

CV: I completely immerse myself in their way of life, in their space. I fall into their rhythm, I live as they do, I don’t take any of my own comforts… I live alongside them, in their way. During the first week (with no camera) I just observe everything, every detail of how they live, of their individual roles, of their relationships etc. I will try to help, usually the women, as most of the daily chores fall to them. I smile (a lot). I play with the kids and spend time with each member of the family (usually they beckon me to go with them). I am totally at ease and comfortable with no common language. Often the friend I have made, who has accompanied me to the nomads, speaks a few words of English (but not always). I feel at home almost instantly where ever I am, perhaps because I have no home of my own and I’m always on the move.

I definitely shoot as a documentary photographer, spending deep time and waiting for beautiful light. I’m conscious always to try to fit in, not to take up much space and as much as I can be part of the family. My camera once out is always with me, as I shadow the nomads’ days and begin to know their way of life. They seem unfazed by the camera and intuitively seem to understand my curiosity of their way of life, sharing with me all aspects of daily life. Towards the end of my stay, I will show them the images I’ve taken on my laptop – they love it and usually they ask to see it all again… and again. I will also try to make sure I get prints to them once I have edited. Obviously, it’s not a simple task getting the prints to nomads, but I usually find a way.

Photography is my part in the storytelling of life – with the hope of encouraging people to reconnect to the land and community, and to be a part of protecting our natural world and all the ways of life that coexist.

MB: How is the climate crisis affecting nomadic communities’ livelihoods and ways of life? What do you hope your work communicates about this?

CV: Nomadic life is on the frontline of Mother Nature’s every mood. The extreme change in weather patterns is being felt by nomads across the globe, with the speed of change, unrecognizable. They no longer know how to read the sky. Everything in the life of the nomad is tied to cycles, cycles that are now being threatened. Rains are no longer predictable; snow falls but in sudden extremes or none at all, in unfamiliar patterns. Severe winters that kill large numbers of the nomads livestock are known as dzuds in Mongolia and the consensus among these nomads is that they are occurring far more frequently in recent years.

Since I began my nomad project, two of the communities that I lived with have been obliged to settle as a result of forced assimilation and the impacts of the rapidly changing climate. As their way of life is increasingly threatened, my images capture something of their way of knowing the world, both as a visual trace for the nomads themselves and to help bring their knowledge into focus. In the face of climate disruption, loss of biodiversity, and the impacts of digital and economic systems, their knowledge is more vital than ever. Exposure is perhaps the most powerful way to change people’s worldviews.

Nomadic life is on the frontline of Mother Nature’s every mood. The extreme change in weather patterns is being felt by nomads across the globe, with the speed of change, unrecognisable. They no longer know how to read the sky

MB: What have you learnt from spending time with these communities: what lessons can be drawn from them?

CV: I have spent many months with nomadic communities across the Himalaya, the Tibetan Plateau, Mongolia’s Gobi Desert and Altai mountains, the Arctic tundra and the Andaman Sea, learning about another way of knowing the world. Across these diverse landscapes and cultures, I have witnessed many common strands in the nomadic existence – spiritual and physical; in survival, resilience and in the fragile connection between people, land and community.

I have learnt about living in reverence with the land and its cycles, about living entirely off and from the land, of how livestock can provide the nomads with everything they need. I have learned how they take only what they need, waste nothing, and leave the faintest imprint on the earth. In how they live lightly, more freely – how they can adapt and be nimble and flexible in their thoughts and actions. In their ability to read and feel the land, filtering everything they see and sense, mapping place and time, wayfinding across the landscapes – they haven’t forgotten how to listen. Their spirit is wild, and their knowledge of the land is deep. I have learnt about how precious water is – digging through layers of ice, or melting snow, or in harvesting rain. In the search for food for their livestock, in learning the language of the land. I have learnt how everything is talked in story, around the fire, in community, and how food is always shared. Of how the elders are their council, their wisdom-keepers, who carry an ancient wisdom of how to live in harmony with nature and how their myths and legends weave into their understanding of the world. A mythical tale protected the Moken (the sea nomads) when the tsunami came in 2004 – knowledge of how to survive laboon/the seventh wave, passed down through the generations. In the face of climate disruption, loss of biodiversity, and the impacts of digital and economic systems, their knowledge is more vital than ever. Exposure is perhaps the most powerful way to change people’s worldviews.

MB: What might the future of our society look like if integrated with these learnings? And what’s next for the Nomad Project?

CV: A vision of living with nature, for the land, the ocean, and in community. A way to hold space for intercultural dialogue among elders of nomadic (and other indigenous) communities to share knowledge on how to ensure the survival of all peoples, animals, territories and all the ways of knowing the world for future generations.

In terms of what’s next, I hope to continue spending time with nomadic communities – documenting their unique ways of knowing the world. To build on the trust I have already established and invite a deeper collaboration to capture their voice and perceptions of the world through other forms of storytelling, to sit alongside my images. And to creatively share this huge body of work of woven stories – to convey different worldviews and deep knowledge of people who live in reverence with the natural world, adapting to change, as they always have done.