Uganda and Tanzania hope to join Africa’s oil boom through a massive pipeline project.

British couple Frankie and Vernon Reynolds are pioneers in East African primate research. As young members of theStanford Center for Behavioral Sciences in the early 1960s, they came to the Budongo Forest in western Uganda to study Eastern chimpanzees. “When the Budongo Field Station for monitoring chimpanzees was then established in 1990, I spent every summer there,” explains Frankie Reynolds, conveying her enthusiasm for this African natural paradise.

This sanctuary is now threatened by a gigantic oil project. After several delays, the first 100 kilometres of line pipe reached construction sites for the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) in Uganda and Tanzania last December, marking the official start of construction on the megaproject.

Frankie’s husband, Vernon Reynolds, founder of the Budongo Field Station and Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at Oxford University, describes the chaos that has descended on the once tranquil forest: “A road, close to our field station, which runs down the escarpment to the lake shore is currently under construction, with huge digging machines, dust and frightening noise.” The Reynolds explain that this disruption stresses both chimpanzees and local residents. “Chimpanzees are like humans in that their behaviour is very much influenced by population density, food availability, and environmental stability. If badly disturbed, chimp wars break out” the couple warns.”

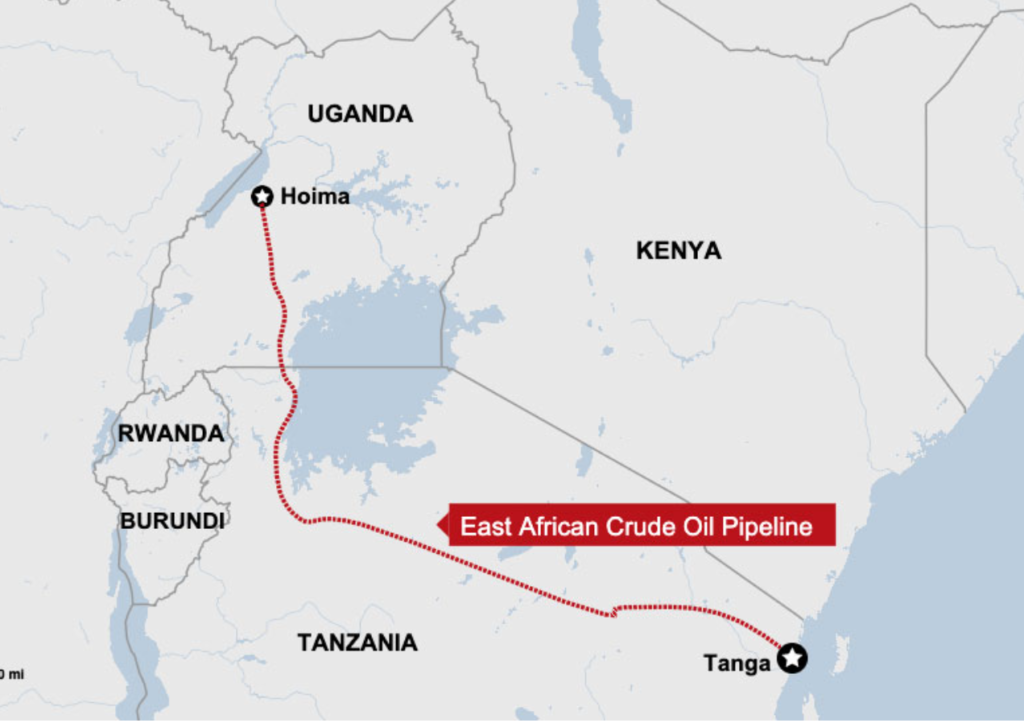

On the shores of Lake Albert, the idyllic landscapes of the Budongo Forest and the Murchison Falls National Park with its iconic African species further north are particularly endangered by two oil production projects: the Tilenga project by French energy giant Totalin Murchison Park with a hub in Hoima, and the Kingfisher project by Chinese corporation CNOOC further south. The crude oil from these fields will then flow through the 1445-kilometre-long EACOP from Kabale on Lake Albert to Chongoleani Peninsula near the Tanzanian port of Tanga, to be loaded onto oil tankers in the Indian Ocean.

The oil is expected to bring foreign currency and prosperity to Uganda and Tanzania. But doubts are growing as to whether the local population will truly benefit, and whether assurances about protecting the region’s fragile environment and endangered wildlife will be kept. Criticism of the EACOP is taboo, especially within Uganda. Authoritarian President Yoweri Museveni has warned environmental activists to “keep their hands off my oil”.

A climate of fear prevails. “We have to tread extremely carefully around some very high-level politics, and careless, if well-intentioned conservation narratives have done more harm than good of late”, explains an anonymous researcher familiar with the situation at Lake Albert.

After an extended exploration and planning phase, the construction of the EACOP between Uganda and Tanzania was agreed upon in 2017. Controversial environmental impact assessments, the also criticised resettlement of people near the oil fields and along the pipeline route, and finally the complicated search for additional investors further delayed the start of construction. Experts estimate that the project will result in the loss of property for 14,000 households.

Ugandan climate justice activist Vanessa Nakate doubts the benefits for ordinary people, comparing the situation to other African countries in the New York Times: “The discovery of oil in Nigeria, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo has not brought widespread prosperity. Instead, it has brought poverty, violence and the loss of traditional lands and cultures.” In fact, only 30% of the revenue will remain in Uganda and Tanzania, with the rest going to Total and CNOOC. “This pipeline is not an investment for the people”, Nakate wrote.

According to a 2022 analysis by the Climate Accountability Institute (CAI), the project will be responsible for emitting a staggering 379 million tons of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2) over its estimated 25-year lifespan – 25 times the annual emissions of Uganda and Tanzania combined. The CAI pointed out that other published figures (which are lower) often only consider the construction and operation of the pipeline, representing a mere 1.8% of emissions. However, the true total emissions would include sources like oil refineries in Europe or China. These figures are entirely incompatible with international climate targets.

In a report published in September 2023 during the African Climate Summit in Nairobi, Kenya, EarthInsight, an environmental organisation specialising in cartography, presented satellite images that show that the environmental impact of EACOP is much greater than previously assumed. According to EarthInsight Director Bart Wickel, the images and maps prove that the project’s official Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) “was piecemeal and only examined individual components in individual countries.” EarthInsight‘s investigation, on the other hand, identified a massive negative impact from the pipeline on three critical ecosystems: Murchison Falls National Park, the entire Congo Basin with a particular emphasis on Virunga National Park, and coral reefs and mangroves along the Tanzanian coast.

“Wellpads that will feed the pipeline and a feeder pipeline itself will cross the Victoria Nile in Uganda’s Murchison Falls National Park, which is a globally important wetland”, warns Wickel.

Uganda’s wetlands host fish and other aquatic life, as well as hippos, sitatunga, Nile bushbucks, waterbucks, leopards, oribis, duikers, and reedbucks. Additionally, Murchison National Park is home to other partly endangered charismatic species such as lions, leopards, giraffes, and elephants. The surrounding forests shelter chimpanzees. The endangered wetlands also support about 420 bird species.

Wickel is also concerned about the impacts on neighbouring DR Congo: “The EACOP project opens a whole new frontier for fossil fuel expansion precisely where the world cannot afford to lose more biodiversity and forest” – in the Congo Basin.

The pipeline provides an avenue for the Congolese government to extract oil in Virunga National Park and then transport it across Lake Albert through the EACOP. The exploration blocks for oil and gas auctioned in Kinshasa have been causing international criticism since 2022. In May 2023, the DRC initiated consultations with Uganda to gain access to their pipeline. Environmentalists have since warned of an ecological wildfire across the entire Congo Basin and beyond.

According to Wickel, these dangers highlighted by the maps are just a fraction of the problems. For instance, the pipeline is supposed to cross more than 200 rivers along its entire length – each leak a potential disaster.

For a long time, hard-to-access oil reserves in Africa held little interest for international energy corporations. However, the supply gap triggered by the war in Ukraine has dramatically changed perspectives – at least in the short term. Especially in Africa, many nations often downplay conservation concerns in light of the temptations created by current energy demands. Experts have identified a critical gap in many Western nations’ energy policies: while there’s a long-term plan to expand renewable energies, there’s also a short- and medium-term need for more oil and gas. As a result, their gaze is turning back towards Africa. According to calculations by the Rainforest Foundation, 10 % of Africa’s surface is already affected by oil and gas production. If all proposed projects were realised, this number could rise to nearly 38 percent.

The particular problem for projects still in the planning stage is that once oil and gas begin to flow through pipelines, the pendulum of energy demand may already have swung away from fossil fuels.