With over 70% of Europe’s waters in poor chemical health, journalist Zoë Casey investigates how persistent PFAS pollutants are seeping into food and water systems, and why farming with fewer chemicals may be key to recovery.

Belgium has been rocked by waves of “forever chemical” pollution scandals. In Antwerp, people living near the 3M chemical factory will see the soil from their entire gardens excavated since it contains unsafe levels of PFAS – a group of synthetic compounds first used in Teflon-coated equipment from the 1940s. 3M has been fined nearly €600 million for the clean-up, but the actual costs on local families and farmers are expected to be far higher.

In Chièvres, a small town in southern Belgium, blood tests on residents have revealed dangerously high levels of these eternal chemicals. Studies show the long-term effects our bodies could include cancer, diabetes and harmful effects on the immune system, reproduction and development. Meanwhile, evidence is emerging that some PFAS breakdown into a particularly tiny particle called trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) whose toxic effects are little known and under-researched.

“I am extremely concerned about the impact on health and, in particular, if and when people exposed will develop serious illnesses like cancer,” said Geoffrey Vanstals, President of local organisation SOS Notre Santé. “PFAS accumulate in water, in soil and in fauna. It’s terrifying to think that we could leave our children and grandchildren an environment that’s irredeemably contaminated,” he added.

“PFAS accumulate in water, in soil and in fauna. It’s terrifying to think that we could leave our children and grandchildren an environment that’s irredeemably contaminated,”

Residents in Chièvres have not been told the origin of pollution, but the picture is no rosier across Europe. The “forever pollution project” has mapped thousands of contaminated sites, finding the sources could be chemical plants that make PFAS, industrial complexes that use PFAS in plastics, paints, varnishes, fire-fighting foams, waterproof textiles – and the pesticides that reach our food and water.

Pesticide’s hidden secret

Speaking at the European Parliament in March, Hans Peter Arp, an environmental chemist at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute, said that PFAS are widespread in everything from our drinking water and eggs to fruit juice partly because they are in the chemicals farmers are spraying on the fields. “If you want to avoid them, drink only very old wine,” he advised.

Meanwhile, a 2021 study on over one hundred beer samples taken from shops and bars in 23 countries across Europe found high levels of TFA contamination. The study identified beer’s main ingredient – malt – as the source, since the cereal crop absorbs TFA molecules from pesticide-contaminated soil, which then accumulates in malt grains.

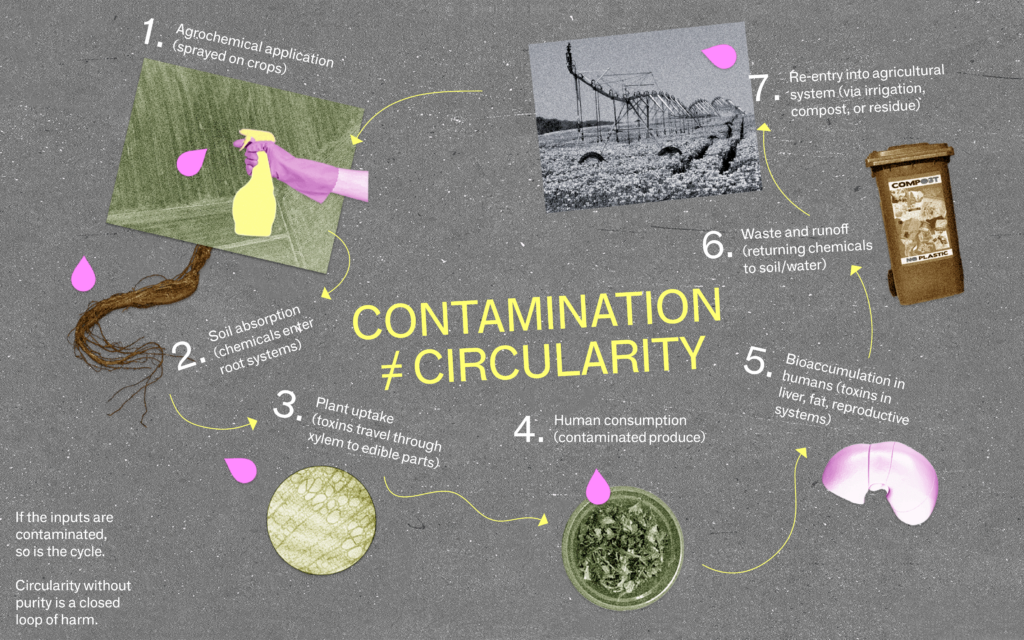

Agrochemical industries started adding PFAS to products in the 1990s due to their staying power on crops and trees, which boosted their efficiency. Pesticides are sprayed directly on fields, leaving PFAS residues on the harvested crop, while they also enter soils and are absorbed by the plant’s roots. When it rains, PFAS contaminated field run-off can enter the environment by leaching into nearby waterbodies.

In recent decades, PFAS pesticide use has risen rapidly. In both 2022 and 2023 sales rose by 20% compared to 2021 in Belgium, according to environmental organisation Nature et Progrès.

Fields are now routinely doused in herbicides, pesticides and fungicides year-round – all of which can contain PFAS. “Farmers are not even aware they are covering their crops with forever chemicals,” said Virginie Pissoort from Nature et Progès. “They buy products in huge containers labelled as toxic, but they don’t know they can also contain PFAS, they don’t know these PFAS break down into potentially even more toxic TFA, and they don’t know how dangerous for nature and people this addiction is on a very long scale,” she said.

Until recently, another source of PFAS was being layered on Belgian fields – the waste sludge from water treatment plants, sold or given to farmers as a nutrient- rich fertiliser. Across Europe, more than half of sewage sludge becomes fertiliser – a practice the EU recommends as part of its circular economy objectives to avoid incinerating it. Under the “sewage sludge directive”, the EU sets the rules for using the sludge – including its treatment and testing for heavy metals – but it also notes that “the set of pollutants which [the directive] regulates needs review”, without indicating when this might take place.

Following evidence of PFAS contamination, the northern half of Belgium – Flanders – took EU rules further and banned the use of sewage sludge as fertiliser in 2000. Southern Belgium – Wallonia – continued to allow the practice from both its own water treatment centres, and those in Flanders, until 2024 when an investigation by Belgian media RTBF exposed the PFAS contamination risks.

Reigning in PFAS

“We’re calling for an immediate ban [of pesticides] because they endanger the right of future generations to live in a healthy environment.”

Around the world, PFAS legislation is patchy to non-existent. The international Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants restricts the use of some PFAS; and some countries, including Canada and the US, have some limits in place. As part of its Chemical Strategy, the EU has committed to phasing out all PFAS for all uses unless they are “proven essential for society”, although no concrete proposals for a comprehensive ban are currently on the table.

Simultaneously, the European Chemical Agency (ECHA) is examining a proposal submitted by Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden to curb the use of around 10,000 PFAS. Crucially, the proposal, which is currently undergoing a lengthy analysis procedure, does not include the PFAS used in pesticides. This is because the five countries claimed that a separate EU rule – the Pesticide Regulation – was stringent enough to catch all toxic substances. They also claimed banning all PFAS pesticides would boost pest resistance to all pesticides due to a fall in the number of chemicals that can be used.

In March, the EU did prohibit Flufenacet – a PFAS pesticide widely used on cereal crops, but 32 other PFAS pesticides are still authorised for use. “Flufenacet disrupts thyroid hormones and may impact brain development so we welcome this move,” said Salomé Roynel from the Pesticide Action Network PAN Europe. “However, a pesticide-by-pesticide approach is not enough – we’re calling for an immediate ban because they endanger the right of future generations to live in a healthy environment,” she said.

Agrochemical lock-in

“There’s an entrenched mindset that it’s not possible to farm outside of the conventional system. But we know organic farmers who are extremely successful and we’re working to spread this message.”

Shifting farms away from an agrochemical dependency to limit PFAS pollution is set to be a significant challenge. “These days farmers are visited by advisors from big chemical companies recommending their products; farming magazines are filled with adverts for agrochemicals; agriculture students learn about conventional chemical agriculture with ‘alternative’ options like organic being optional side modules,” said Pissoort.

“There’s an entrenched mindset that it’s not possible to farm outside of the conventional system. But we know organic farmers who are extremely successful and we’re working to spread this message”, she added, noting that sufficient support and subsidies are available to help farmers transition.

Meanwhile, chemical companies are accused of cover-ups – 3M has reportedly known about the presence of PFAS in human blood since the 1970s – and of using tactics that delay actions to limit their manufacture. According to PAN-Europe, agrochemical lobbies are also regularly attempting to undermine European Union moves to limit PFAS in pesticides.

Roynel points to the urgent need to shift from chemical-thirsty monocultures by using well-known methods that include crop rotation over several years, cover crops during winter, mechanical weeding and some use of bio pesticides made of natural substances.

“The pressure civil society is now putting on the EU and national governments is only going to grow. This rising awareness must force the EU into taking serious action to protect our future,” she said.

As communities like those in Antwerp and Chièvres come to terms with local PFAS pollution, encouraging farmers to switch away from agrochemicals to more sustainable, less intensive agriculture does seem to be an accessible way to limit the contamination dangers.