After nearly 100 years of tea growing at Brackenhurst in Limuru, Kenya, which saw the introduction of invasive species like eucalyptus and cypress, the soil has become barren. Now a group of conservationists are reforesting the land with indigenous seeds.

The highlands of Limuru, north-west of Kenya’s capital city of Nairobi, are serene. At 2,000 metres above sea level, this landscape – known for its seemingly boundless tea plantations – is often swaddled in a slight fog. The rains came in April 2023 after three years of drought, amplifying the lushness of the region. The trees are reawakening; flowering shrubs are bursting with tender buds and curling vines.

Traditionally, the Kikuyu people, the dominant ethnic group in Kiambu County, had their own systems for dividing the land to graze cattle, farm and build homes. But in the late 1800s a land grab by the British government brought a major shift – resources from the land were produced and harvested at an industrial scale. The primary-growth forests in the region were razed for tea estates or to grow commercially viable, non-native trees – mainly eucalyptus and cypress – for timber, which contributed toward financing the colonial government. Nearly all of its endemic flora and fauna were eradicated. This biodiversity collapse mirrored the ongoing mass deforestation occurring across the country (US-based NGO Global Forest Watch reports that from 2002 to 2021, 14% of its primary tree cover was lost).

Across Kenya’s forests, the Ogiek and Sengwer communities have been, and continue to be, evicted from their ancestral homes and forcefully assimilated with bigger ethnic groups. This treatment of Kenya’s forest-dwelling communities – deliberately overlooking the stark differences in the customs and language of each community – continues to this day, marginalising them and denying them political representation.

The Kikuyu people were also forced off to make way for tea growing. At present, 60 years after independence, the British fostering of Limuru’s tea industry explains the region’s lack of a native community––most Kenyans working at the estates are bussed in and out for each working day. Limuru remains Kenya’s bedrock for tea-producing, processing, and international exports.

Also in Limuru, Brackenhurst was established as a hotel in 1914. Its 100 acres became a popular holiday spot for colonial families and British soldiers. In 1964, a year after independence, the land was purchased by the Baptist Mission of Kenya for $10,000 as the first iteration of Brackenhurst Botanical Garden and Forest. Despite the religious overtones ecological conservation is a focus at Brackenhurst. In 2000, Mark Nicholson, a veterinarian who trained at The University of Edinburgh and Cambridge before translating his interests to botany, embarked on a 30-year project to convert Brackenhurst back to its native tropical montane state. (Three-quarters of the original Brackenhurst was retained for ecological conservation, with 50 acres sold to the Theological College of Kenya for a church campus). The original blueprint was for an arboretum, yet Nicholson and his team soon realised that an actual forest, with its vigorous understory layer of herbs, ferns, orchids and shrubs, would best enhance biodiversity. The eucalyptus, cypress, wattle and pine were uprooted and replaced by more than 120,000 seedlings and wildings of trees, shrubs and scramblers – species mainly from East Africa and a few from Central Africa. Apart from the forest, there’s also a small garden featuring one hundred indigenous herbaceous species.

A decade after overthrowing the monoculture plantations, a closed canopy was restored in the regenerating forest. In 2015, the Colobus monkey – a strong biodiversity indicator – re-emerged after 80 years of absence. Other critters such as bushbabies, African clawless otters, hedgehogs, and civet cats have also reappeared. There are now 180 bird species, up from just 30 at the start of the project.

Besides building up biodiversity, regeneration has also eased the strain on the soil. Non-native species tend to grow at lightning pace, sucking up vast quantities of water from the ground. After nearly a century’s worth of eucalyptus plantations, says Nicholson, it’s no small wonder that the soil has turned barren.

This restoration process safeguards ecosystem services, returning the environment back to its natural pace. After a long hiatus, perennial stream flow through the forest has also returned. Today, the forest has been restored with 358 indigenous tree species, such as Widdringtonia whytei (Mulanje cypress – a rare hard softwood tree native to Malawi), Afrocarpus falcatus (African pine tree), and Prunus africana (African cherry).

In the forest, there are also a number of strangler figs, which the Kikuyu people call Mugumo. The Kikuyu people believe that Mugumos, which can grow as tall as 90 m metres over hundreds of years, are sacred. Besides preserving soil structure and fertility, the tree also provides medicine, fruit and a place to hang beehives, as well as a shrine for Kikuyu spiritual rituals.

Some Kikuyu people claim that the Mugumo is literally part of them – a physical manifestation of their cosmology. The felling of a Mugumo indicated the end of an era. The Kikuyu seer Mugo wa Kibiru had predicted that British settlers would leave if a certain Mugumo in Thika, a town northeast of Nairobi, died. His words worried the British, who feared that the Kikuyu – specifically, the Mau Mau independence fighters – would demand freedom should the tree die. They protected that tree, a site of worship, with a reinforcement of metal bars and an iron ring packed with soil. But the tree was struck by lightning in 1963, and the British left shortly afterwards.

In late 2022, the Centre for Ecosystem Restoration Kenya (CER-K) was established to focus more squarely on ecological restoration. With a base in Limuru, CER-K also runs projects in the Maasai Mara, a famous safari destination, and Kilifi.

Mercy Sigei, CER-K’s landscape technologist, references Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring as laying the foundation for her work, saying: “I don’t want to get to a place where all the birds are gone.” Landscaping is not about solely focusing on beautification, she says, it is also about considering how different actions and chemicals impact the greater ecosystem.

The biggest challenge at the moment, Tobin Mutiso––CER-K’s taxonomist––reveals, is that although this 20-year-old forest is growing well and looks good, there’s a curious lack of regenerates (self-propagating flora) among the trees, and very few herbs. The team doesn’t know exactly why this is, but he suggests that perhaps invasives are choking out natives since they grow faster. Two especially stubborn species – Solanum Mauritianum and Cestrum Aurantiacum – still crop up on the forest floor. CER-K is waiting for microscopes and other lab equipment to continue their investigation: identifying insects inhabiting the forest and better understanding the soil composition will help them understand better how to support the regenerates.

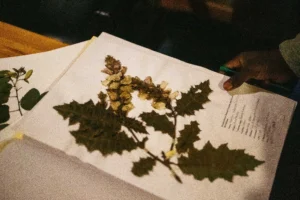

The availability of plant material is another challenge. In 2022, CER-K established a seed bank to address this shortage with the support of Terraformation, a US company that offers carbon credits to its investors and early-stage financing to biodiverse carbon projects. This seed bank is one of the few in Kenya that focuses on indigenous species.

“We like to say that [Brackenhurst is] a forested island in a sea of tea,” says Jono Jenkins, a project coordinator at CER-K. “At some point, this would have been all forest.”