Produced in collaboration between Icarus Complex Magazine and the Indigenous led organisation If Not Us Then Who?

A lesson from the Indigenous movement in Brazil as the Free Land Camp marks its 20th anniversary.

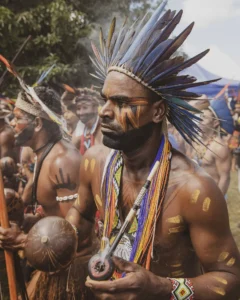

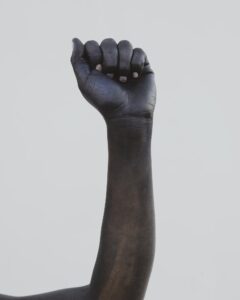

Standing at the entrance to the plenary hall of the Free Land Camp on April 22 was a surreal experience of colour, beauty, emotionality, and mostly, power. The Camp, which exists to unite the indigenous movement in Brazil around a week of political, cultural and resistance actions, was celebrating its 20th year. We were witnessing history being made – a history of resistance, with a Camp that strives to fight back against the effects of Human Rights violations and brutal land exploitation in indigenous lands in Brazil, and that tackles the more than 500 years of colonisation that Indigenous Peoples have faced in this country.

Each year the Camp has returned to Brasilia to take over part of the esplanade, a long strip through the heart of the capital, culminating at the Plaza of the Three Powers – home to Congress, the Supreme Court and the Presidential Palace. This year it surrounded Brasilia’s planetarium, taking over the land around it with tents, crafts, tributes and political sessions. As we walked through, we tried to take in what the Camp means, with its capacity to weave bridges between the past, present and future. The past, in tribute and remembrance of the history of the movement and its fight to keep the territories standing; the present, in demand for recognition of traditional knowledge as a fundamental tool to fight climate change, and for the protection of the lives who stand in the territories guarding them; and the future, in dreaming and planning for a world where the movement holds power, decision capacity and freedom to care for Nature, as they have been doing ancestrally.

With more than 8.000 peoples from over 200 communities gathered together, the Camp has an air of hope, defiance and mourning.

The first Camp rose in 2004 as a response to the Ministry of Justice’s failure to comply with the Constitutional obligation to demarcate Indigenous lands. It was then that the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) started to form, officially coming to life in 2005.

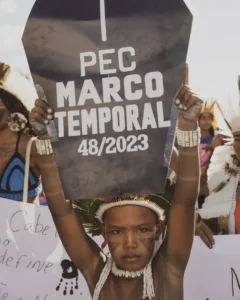

Now, after 20 years of resistance inside and outside the Camp, the demands of the indigenous movement in the country are, sadly, in many ways the same as they were then. For the past few years, APIB and its grassroots organisations have been fighting Marco Temporal, also known as the “Time limit trick”- a series of legal attempts by Congress to stop the land demarcations that are mandated by the Constitution. This theory argues that communities who weren’t on their land at the time the Constitution was signed in 1988, should not have their territory demarcated. Of course, at that moment, hundreds of communities had been forced out of their lands by extractive industries, land grabbing, extensive farming and the military dictatorship that had ruled the country between 1964 and 1985.

It is not just a matter of cultural and spiritual survival, but also of the preservation of Earth and its diversity. Science has shown in the last decade that Indigenous Peoples protect 80% of the world’s biodiversity, despite having ownership over less than 10% of their traditional territories. Their traditional knowledge leads to drastically reduced levels of deforestation versus the results of protected and closed reserves, and the conservation of cropping and medicine seeds holds the secret to food sovereignty and healing power for humanity. Those who are protecting some of the worlds’ most biodiverse ecosystems are fighting legislation that doesn’t believe they have the right to stand on the lands they protect. In response, communities and their leadership fight back with their full collective power.

“The colonisers of the 21st century better be prepared, because their adversary is here now. We will only move forward as humanity if we are inspired by the wisdom of Indigenous Peoples” Celia Xakriabá, indigenous Federal Deputy in Congress, at the Free Land Camp 2024.

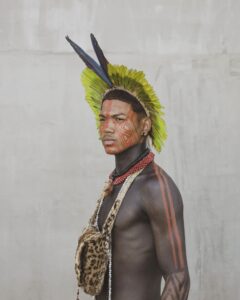

So between the 22nd and the 26th of April, we walked the Camp, joined the marches and asked leaders from multiple communities for their stories and their images. We wanted to share with the world what the indigenous movement in Brazil means when talking of resistance. What we found is that resistance is defined by a myriad of emotions and stories, often conflicting ones, but most importantly by the passion and fight that lives in their blood and their spirits.

Sometimes, resistance means pain. The pain of communities who have lost their elders and knowledge holders to invasive violence, it means a gut wrenching pain that takes over the Camp with each tribute that is paid to lives lost. Just in the past year, the movement has faced massive losses such as the murder of Nega Pataxó Ha Ha Hae, one of the most important healers of her community, in an attack by a group of gunmen who wanted to seize their land to grow monoculture plantations; as well as the killing of two Guarani spiritual leaders by religious extremist groups that were burnt to death because of their religious beliefs by evangelical extremist groups; on top of this there is a massive suicide crisis that communities in the Land Back movement are facing, as despair consumes them. Out of grief, the Camp came forth with the resistance of a communal mourning, which embraces these deaths through chants, candle lit sit-ins and a remembrance of the wisdom lost with each murdered elder.

On the 24th of April, as a group held a chanting tribute to mourn the Pataxós murdered, Kretã Kaingang addressed the plenary only months after the death of his 14 year-old daughter, who tragically took her own life. “Indigenous youth come to me and hug me, asking me to be strong, and they don’t realise that I am strong, so strong to endure this pain every day, and it is me who wishes for them the strength to keep resisting in the face of all the attacks that come their way” proclaimed Kretã to a visibly emotional audience gathered before him. His mourning was met by embraces from all the youth standing on stage with him, and with cries for justice from the Pataxó mourners in the tents surrounding the main plenary.

But the grief of losing their leaders and healers is an act of resistance. It transforms, going from an unbearable pain, to the clarity of knowing that those who leave them do not die in vain. Resistance, then, is also to honour the fighters that came before and to take their wisdom to the next generation.

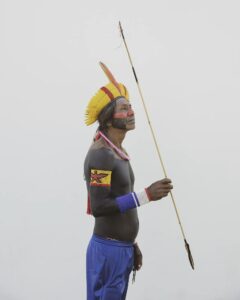

During the days of Camp that followed, we ran into a myriad of body painters from multiple territories. They cover the bodies of the attendees with paintings made of ‘genipapo’ and ‘urucum’, traditional fruits with heavy black and red dyes. The paint is etched onto people’s skins manually using traditional techniques, and the aim of covering the body with paint is to provide protection. Since the communities gathered at Camp are getting ready to march towards the Congress and the Presidential Palace, bringing their demands to the government, the paint applied is an extra layer of spiritual coverage from any threats they may face. The paint, which lasts for a couple of weeks as it fades slowly out of the skin, mimics patterns of animals like the cobra, the jaguar and the turtle, depending on their lands and traditions, and it shields the bearer against attacks, whilst also honouring the history of their territories.

On April 25th, as they were painted, they prepared to march across the vast expanse that holds all the ministries and into the square of the three powers, where the Court holds the case against the ‘time limit trick’. While this legal framework had already been overruled by the Supreme Court, Congress included several of its articles in new legislations which have now been approved, and this is why the Association of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, APIB, has filed a case, once again, in the Supreme Court against it and is waiting to know when and how it will rule. If the ‘time limit trick’ is not overruled in the Court, hundreds of thousands of hectares of standing forest would face the threat of land grabs, leading to further deforestation, and subsequently large-scale cattle farming and agribusiness moving in, Indigenous Peoples all over Brazil would be evicted and attacked in their traditional territories, and countless species would be lost in the sites currently protected by them.

Those traditional territories are not solely the home of necessary species and resources for human survival. They are also lands where an education, health and policy revolution is taking place, in the hands of Indigenous Peoples. Communities now have official Indigenous health secretaries, education policies that favour traditional knowledge being taught in official schools, and some first steps in policy making that are aiming to protect isolated communities. While these acts and positions of transformation are gathering strength, the new generations remain steadfast in resistance to support the elders that lead them. With this youth, comes yet another meaning of resistance for the movement.

At the Free Land Camp, sometimes resistance is hope.

The babies, toddlers, children and youth at Camp bring a renewed sense of possibility. For many of them, it’s their first time at Camp, the first time feeling like they are less alone, like they are a part of a mass that resists in the face of destruction. In the homes where they come from, many of the youth have local language preservation initiatives, bioeconomy processes that recover native seeds and traditional ingredients, and are even leading lawsuits against multinational corporations for issues like river pollution and the impacts of infrastructure mega projects on the forest. Many of the youth pair this work with positions such as forest monitors or firefighters. They have created brigades that track invaders of their lands and stop the wildfires that spread out of control. Those lands where they have recognition and control, have reached deforestation rates tenfold lower than government reserves or territories that are unrecognised.

“Step lightly, step lightly, if you can’t handle the ants, don’t mess with the ant-hill. Step lightly, step lightly, if you can’t handle indigenous women, don’t mess with their lands” Indigenous chant sang by the Indigenous Women’s Association of Brazil- Warriors of Ancestrality (ANMIGA)

As communities continue to protect territories where the State is absent, and oftentimes feels like the enemy, they see resistance also as an act of rebellious innovation for a future where resistance is no longer needed. At Camp, the tents rise every morning as the communities gather to march to the plenary discussions, meet with ambassadors and receive the indigenous politicians who come to listen to their constituency. They meet every day with a plan for action that supports their belief that a better future is possible.

We bore witness to these acts of innovation, every day from the beginning to the end of Camp. In order to even be able to come to Brasilia, the communities have worked for months to raise the funds to make their journeys, holding communal fundraisers, hosting cultural sessions in their territories and selling artworks and crafts; they created grant applications to receive official and non official funding; and partnered with movements who could bring them and feed them during the five day gathering. This movement then became a nation-wide flotilla of buses travelling for up to 5 days from the most distant territories, canoes taking delegations to the closest ports and airports, and endless hours of walking to get close to places that could help them reach Brasilia, all of this while carrying communications equipment, crafts and traditional paintings, musical instruments and their tents, as well as their regional and local political statements.

Once in Brasilia, all the delegations set up camps that allowed them to keep dry in the rain that took over the city for the first two days. They dug furnaces to keep fires burning and prepare their food and created artisanal clothes hangers to dry off from the rains. This resistance, in the form of adaptability and creativity on the ground, was not only a central part of the arrival and financing process, but also kept a dialogue with communicational, campaigning and even health aspects of the Free Land Camp.

We bore witness to the makeshift plenaries formed in every corner of Camp, consolidating messages that were then carried through the capital in the form of actions like the massive ‘cobra of time’ that marched up to the Presidential Palace, or the projections that turned the blank Senate and Congress into a rainbow of feathers, faces and messages declaring “Our time frame is ancestral, we have always been here”. These messages reverberated beyond the bounds of the city thanks to the work of hundreds of communicators, including the first legally formed Indigenous communicators association in the country, Mídia Indígena. All bringing their cameras, drones, microphones and cellphones to tell the story of Camp to those back home who need the inspiration to keep going.

It feels like a story too big to tell, as if your eyes were envisioning creative moments with every heartbeat, and the massive responsibility of telling the story seems impossible when you are surrounded by the billions of ways in which the indigenous movement is a living testimony to the act of resistance. This resistance, with all the moments in which it changes and stops being one thing to become another, does have a set of rules that make it as great as we see it today. The resistance of the Free Land camp is always about the unity in surrounding themselves with others who are fighting for the same cause. It is always and unquestionably about the wisdom that has been passed down for generations and refuses to die. And it is without a doubt, the resistance of thousands of hearts that beat with passion for the belief that they, as protectors and stewards of Mother Earth, can help guide us from a climate crisis that is rapidly draining the health of humanity and our planet.

COMING SOON

Genilson Guajajara photographs will appear in the September print issue of Icarus Complex magazine. Online series coming soon!

Dear Reader, you can support the efforts of APIB by making a donation through this link.