Francesco Merlini on Glaciers and Geotextiles

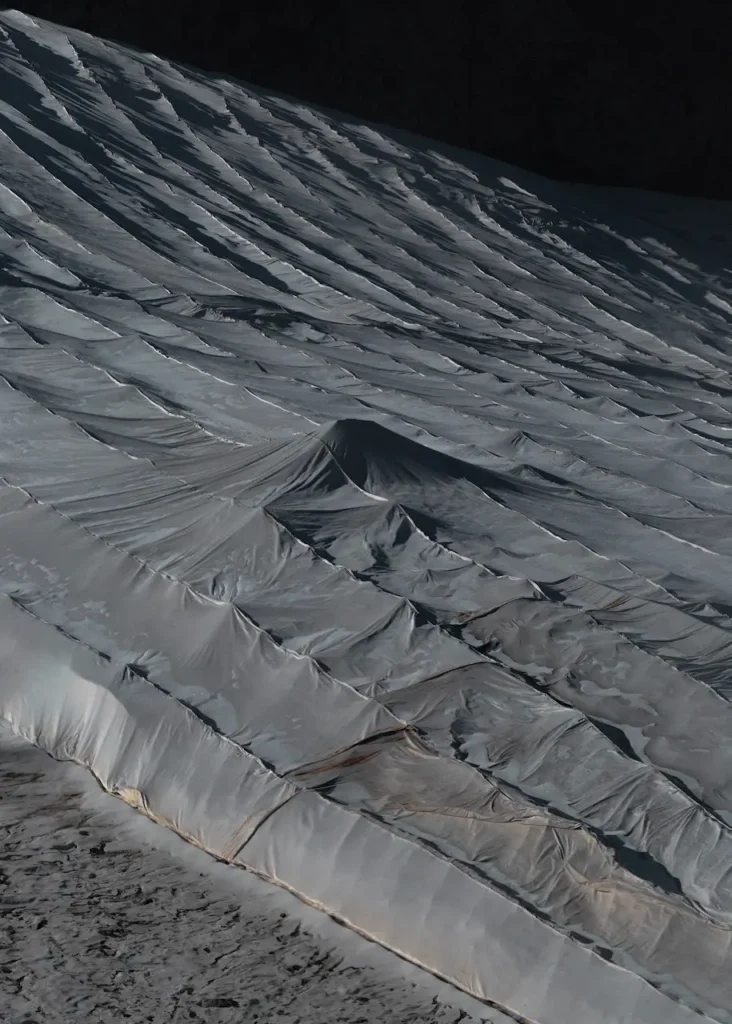

Francesco Merlini is an Italian photographer based in Milan and working primarily on personal long-term projects and editorials. Trained in industrial design, he is always looking for a point of contact between his documentary background and a strong interest for metaphors and symbolism. He was selected as part of The Talent Issue: Ones to Watch by the British Journal of Photography in 2016, was shortlisted for the Prix HSBC pour la Photographie in 2020, and was a nominee for the 2021 Leica Oskar Barnack Award. In 2023 he was shortlisted in the Sony World Photography Awards. Francesco’s last book, Better in the Dark than His Rider, was published in 2023 by Depart Pour l’Image. His project, Cloth, portrays motionless synthetic waves, stains of futurism that break the rocky uniformity of a familiar landscape, and examines the global warming-driven destruction – and scientific attempts to save – the Presena Glacier. Since 2008, the glacier’s slopes have been covered each year in geotextile sheets to protect it from melting. Lying atop the glacier, they reflect sunlight and protect the underlying snow and ice layer from heat and ultraviolet rays. 25 meters long and 2 meters wide, they are placed in June and removed in September by specialized workers who, moving as equilibrists on the ice, unroll and sew together this huge blanket. Yet the melting of the glaciers shows no signs of subsiding, instead proceeding at an ever more pressing pace: a recent study published in Nature found that the ice of the Alps is now melting six times faster than in the 1990s. Cloth is on view at Lugano’s Artphilein Foundation until 21 December 2024. Writer Madeleine Bazil speaks with Francesco about this body of work, the changing landscape, and an artist’s role in our current climate emergency.

Madeleine Bazil: How did this body of work begin: how did you first hear about (or become interested in) the Presena Glacier and geotextile sheets?

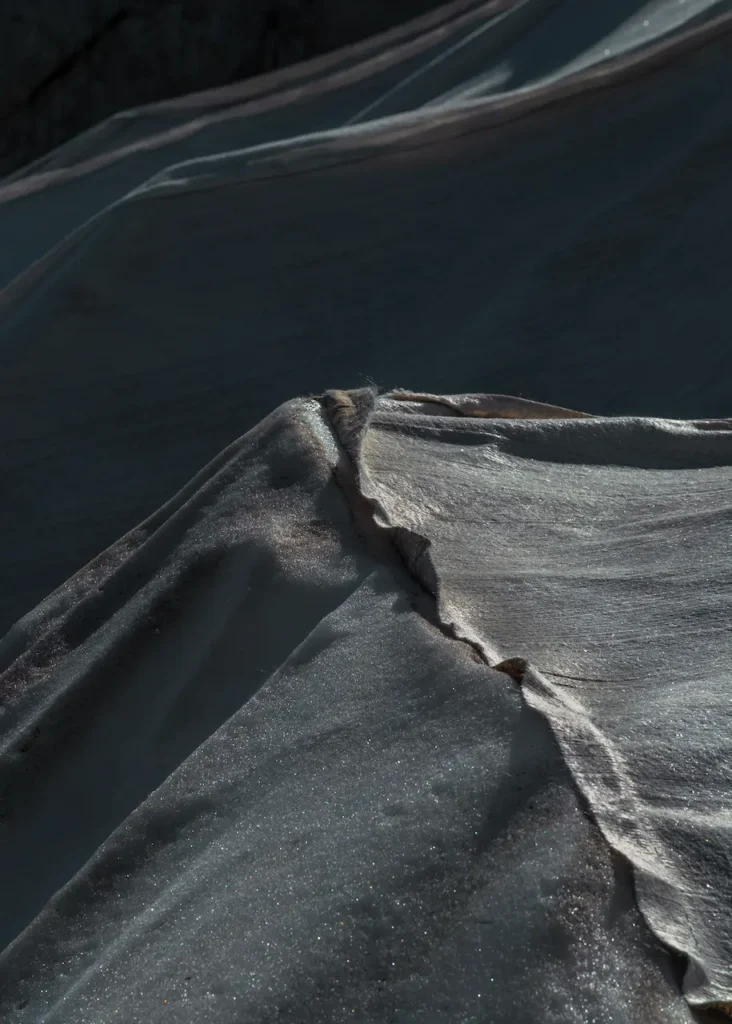

Francesco Merlini: Several photographers took photographs of glaciers covered with geotextile sheets in the last two decades with different visual languages that span from more photojournalistic to more personal ones. Almost all of them have been taken on one single glacier, the Rhone Glacier on Swiss Alps, the first and the most famous place where this practice has been accomplished. I’ve always been very fascinated by the visual aspects of this phenomenon and especially from the surreal complexity that emerges from the clash between the shapes of the ancient ice structures created by nature and these decadent and at the same time futuristic blankets that makes me think of old artworks or furniture covered with fabric during, for example, a restoration process or a relocation.

I love to include in my projects elements that are invisible, symbols, metaphors that transform a very specific situation into an archetype. Because of this inclination, it’s many years that I’ve thought that it could have been very interesting to accomplish a project about this topic and challenge myself to realize a series with a visual language that, although influenced by the previous photographic approaches to this subject, would have been original and consistent. Because of the attention that has always been given to the same Swiss glacier, when I discovered that also in Italy this practice takes place on the Present Glacier, near Tonale Pass, I didn’t have any hesitation and few weeks later I was there, on the ice, taking photographs of the only Italian glacier where geotextile sheets are used to protect it from melting during summer months.

MB: Your images are really textural, and some almost feel abstracted. Could you tell us more about what you’re aiming to do visually with this work?

FM: I’ve always loved to transform reality into something subjective and ambiguous, creating photographs that most of the time are suspended between perception and meaning. When I shot, I put a lot of efforts in not including in the frame too many elements that would saturate of informations the viewer without living enough space to his mind to move and to fill the holes with his personal visual and emotional alphabet and memories, creating a connection with the image that, otherwise, it would be out of reach, too narrow and precise to step into. This is why, while shooting at this specific subject, in most of the images, I tried to leave outside of the frame all those elements, both artificial and natural, that would very easily define the place and the situation we are in.

Just in very few pictures there are elements, like humans, that suggest the size of the landscape we’re watching. The massive dimension of this phenomenon is the first thing that impressed me. When I watched for the first time this huge piece of nature, wrapped in plastic, the resemblance with the work of the artist Christo was inevitable and this dimensional element has become crucial to me, it has become an element to create astonishment but also confusion. What we see could be big as a car or big as a mountain; it’s hard to tell, you need to focus and nowadays make people spend time on an image, make them squint, it’s something very precious, something that has almost a political value.

The aim of this practice, to cover glaciers with geotextile sheets to protect them from sun rays, is very laudable and positive but this operation is accomplished with bulldozer, snowcats and brute force and in the images I looked for this contrast between these immaculate surfaces, almost celestial, and this very earthly, violent activity, necessary to reach the goal.

This subject has been perfect to create images that, especially for the people who are not familiar with mountains, are unbelievable, absurd and difficult to understand. The light, the iridescent colors, the framing are all elements that have been used in order to intensify reality with the aim to create a visual short circuit between reality and fiction, between surprise and knowledge.

MB: What do you hope people take from this body of work/the exhibition?

FM: I think these landscapes are very complex: complex like it is, from a philosophical point of view, the whole phenomenon of using technology to try to save nature from the effect of something that human progress has caused in a paradoxical, never-ending circle of disregard, responsibility, fear and intervention. What’s happening in this place – like in some other glaciers in Austria, Switzerland and France – is just a desperate attempt, clumsy even if fascinating, to solve a situation that already plummeted. We cannot save these glaciers but we can only slow down their inevitable demise. I really hope that the beauty and the fascination of the landscapes of these images would act like a magnet for people’s minds, creating curiosity and especially knowledge about this phenomenon, about this emergency. It’s too late to really do something for these dying giants but we still can save other glaciers and we can still take care of the many ecological issues around the globe that need to be known and that need immediate interventions. Landscapes like these ones should not exist.

MB: What do you think is the role of an artist in this time of climate crisis/catastrophe?

FM: Maybe I became a photographer because it’s the closest thing to being an explorer that arrives in a place for the first time. Even if I will never be the first human to arrive somewhere or to see a phenomenon, I could be the first person to look at it in that way, and this will always belong to me. I explain this because I think that now more than ever, the way an artist shows and deepens a topic is crucial in order to produce an effect on the viewer. I think a photograph is relevant when it arises a question. I think an image is important when it activates connections in the viewer’s mind with his/her personal experience and background. Even in documentary photography, the author has to be present in the frame, has to be cumbersome in his work with his decisions and his opinions in order to produce something that really touches the audience, suggesting alternative ways to look at something, something that very probably is already known through traditional medias that for sure are effective in showing the climate crisis effects and related catastrophes but are more and more incapable of producing an answer or a reaction in a anesthetized and distracted mankind.

Now more than ever, especially with younger generations, art can be an effective and universal instrument to produce awareness and activate a chain of tangible actions that, summed [up], can be a collective and real answer to the catastrophic reality we’re living.