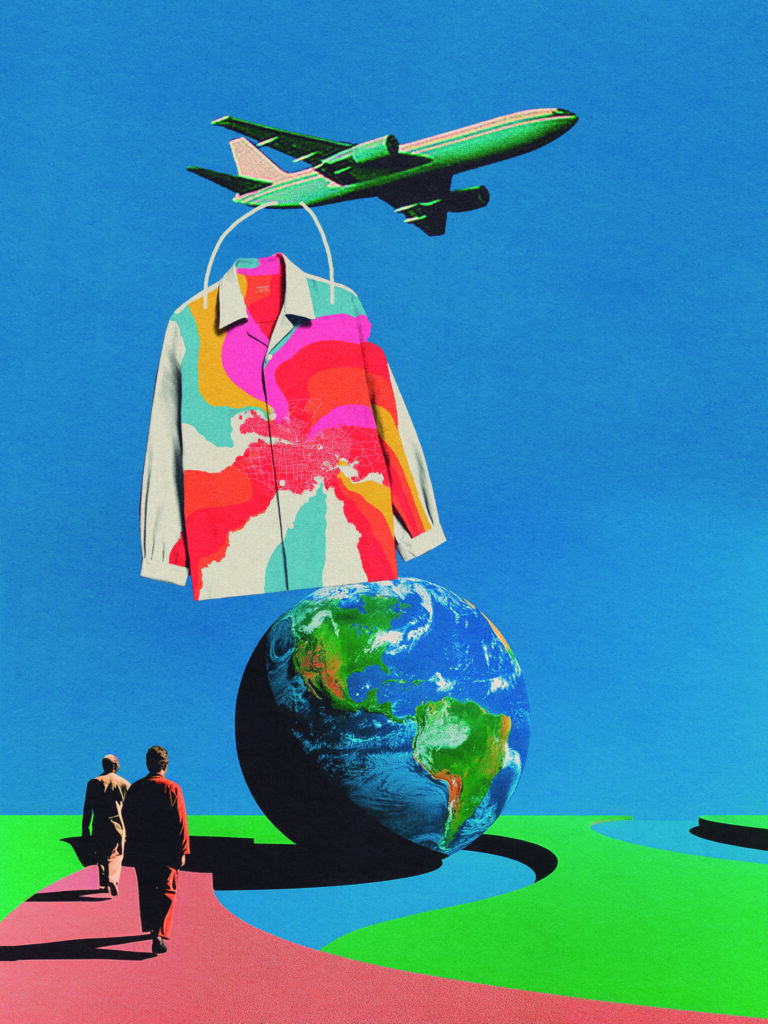

A single cotton shirt today might be designed in Paris, spun in Pakistan, dyed in China, stitched in Cambodia, and sold in New York.

The fashion industry has become a geography of logistics, its beauty underpinned by one of the most globalised, fragmented production systems on Earth. This sprawling network didn’t arise through one, or a handful, of brand’s decisions. The industry-wide system evolved into its current state through a combination of trade policies, tariff regimes, and corporate incentives to reduce cost and produce more which rewired where and how clothes are made. What began as an economic experiment became an architecture of dependence on low-cost labour, deregulated markets, and vast areas of natural resources.

The offshoring of fashion’s labour didn’t happen overnight, it unfolded over decades, shaped by shifting politics and profit margins. After World War II, as Western economies boomed and consumer demand for affordable ready-to-wear soared, domestic production costs began to rise. By the 1950s, American and European manufacturers, in an effort to maintain low retail prices and high margins, started sending sewing work to Japan, Hong Kong, and later South Korea and Taiwan. These countries offered lower cost labour and loosely regulated work environments from governments rebuilding their economies through export-led industrialisation.

By 1974, this growing trade had outpaced existing regulatory frameworks. In response, Western nations pushed for the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) which was a global system of quotas that controlled how much textile and apparel each developing country could export to wealthy markets. On the surface, it was meant to protect U.S. and European jobs but in practice, it codified the idea that garment production was something to be managed offshore. Factories sprang up in countries that had “unused quota” such as Sri Lanka, Mauritius, the Dominican Republic. The MFA created a game of trade arbitrage: when one nation hit its limit, brands simply moved their orders to another. What had once been a domestic industry was now a mobile machine, optimised for flexibility and cost.

In the 1980s and 1990s, governments in the U.S. and Europe embraced free trade as both ideology and strategy, and apparel production’s center of gravity moved decisively south and east. Free-trade zones proliferated, tariffs fell, and corporate deregulation allowed brands to build vast offshore production networks without ever owning a single factory.

The 1994 Uruguay Round of trade negotiations created the World Trade Organization (WTO) and began phasing out the MFA through the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC). In North America, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), signed in 1994 as well, eliminated tariffs between the U.S., Mexico, and Canada. Apparel companies seized the opportunity. They shipped U.S.-made fabrics to Mexico’s maquiladora zones for low-cost assembly, then re-imported finished garments tariff-free. This “production-sharing” model made border-crossing central to manufacturing and entrenched a two-tier labour system—skilled design and management in the North, low-wage sewing in the South. Europe followed a similar model in 1995 through its Euro-Mediterranean Partnership agreements, connecting French and Italian brands with Tunisian, Moroccan, and Eastern European factories. Each policy iteration translated cultural proximity into cost efficiency.

The “production-sharing” model made border-crossing central to manufacturing and entrenched a two-tier labour system—skilled design and management in the North, low-wage sewing in the South.

By 2005, all quotas established through the MFA were gone. China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 sealed the deal. Suddenly, Western brands could source from the world’s largest labour pool without quota restrictions. U.S. imports of Chinese clothing grew nearly fivefold within a decade. The same pattern repeated across Europe, where the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) gave tariff-free access to low-income exporters, and bilateral free-trade agreements

What followed was a production tsunami: apparel manufacturing consolidated in the countries best able to deliver volume and speed which were chiefly China, Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam.

Designer Mary Ping experienced these conversations firsthand: “When factories meet with clients the conversation isn’t about reviewing the line for the next year or two. It’s always ‘is this election going to affect labour costs, oh it doesn’t look like US trade is looking so good, can you move your manufacturing to the Philippines?’ Because it’s such a large scale that the conversations turn into a labour issue. That’s why so much ends up in Philippines and Bangladesh because they can pay workers a nominal wage.”

Even after quotas disappeared, tariffs continued to shape production decisions. Under preferential trade programs, like the EU’s GSP+ or the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), countries receive reduced or zero tariffs if they meet certain governance criteria. Brands use these agreements strategically, moving orders to countries with the best tariff access at any given time.

A factory in Cambodia might assemble garments from Chinese fabric to take advantage of GSP preferences, even though the raw materials traveled thousands of miles. The result is a chain of transactions optimised not for craftsmanship or sustainability, but for trade advantage and lowest cost. For the brands, this model offered flexibility and scale. For workers in the US and Europe, it introduced precarity as the default. Garment labour, once protected by unions in Western cities like Manchester or Lowell, became an invisible export of human energy. Textile hubs that once powered towns in Europe and North America lost mills, middle-class stability, and cultural identity.

Annie Waterman, founder of AOW Handmade who has spent the past 16 years travelling the globe and building relationships between artisan suppliers and retailers has seen this loss first-hand: “I see a dramatic loss in Europe…Portugal for example, just lost its last remaining wool scouring (cleaning) facility and without this, local wool manufacturers can no longer source from their own backyard-the whole supply chain is broken now.”

Outsourcing also allowed Western brands to claim distance from production risks and worker conditions and treatment. The structure of subcontracting, where suppliers subcontract further to meet volume, means brands can benefit from low prices without legal accountability for conditions. In 2013, the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh exposed this hidden network: more than 1,100 garment workers died when an overloaded factory building crumbled. The disaster briefly pulled global attention toward supply-chain opacity and many new oversight initiatives have been formed and many factories have vastly improved conditions. However, many compliance audits often remain self-reported and local inspectors and authorities are incentivised to keep factories open as often it is the only available work in the region.

In Bangladesh, garment workers earn on average less than $100 a month—far below a living wage. In Cambodia, minimum wages hover near $200. These figures persist because the global system rewards cost-cutting above all else. Western retailers set target prices that manufacturers can meet only by squeezing labour.

As Chana Rosenthal, founder of reDesign Consulting explains: “These companies are under pressure to improve shareholder value year after year while grappling with the upper limit of what consumers will pay and relying on margins for growth. This drives down the bottom line and pushes the pressure onto the workers. Our current system focuses solely on cost to fuel workers conditions.”

She adds sub-contracting is still pervasive and that it’s difficult to track down information who they are and where they operate.

Even when working conditions are safe and fair, garment production has taken an environmental toll on the areas it has moved to as well, affecting local populations.

Dyeing and finishing fabrics are among the world’s most polluting industrial processes. Textile production overall is estimated to be responsible for about 20% of global clean water pollution. In Dhaka, the Buriganga River runs black from textile effluent; in Tirupur, India’s dye houses have poisoned groundwater; in Guangdong, factory wastewater carries heavy metals downstream. While people have been told to stay away from the water and not to ingest it, many have no choice and have suffered from dermatitis, contact rashes, intestinal problems, renal failure, and chronic bronchitis. These rivers tell the truth that marketing campaigns obscure: much clothing is subsidised by unseen contamination.

In India, once home to hundreds of indigenous cotton varieties, the introduction of monocultures and industrial farming enabled the country to become one of the world’s largest cotton producers, yet farmers today face declining soil health, increased pesticide reliance and rising debt.

As Aditi Mayer, sustainable fashion activist who works with artisans and farmers in India shares: “In Punjab, the legacy of the Green Revolution is etched into the soil. Cotton, once part of a local textile economy, became a global commodity. The shift severed long-standing links between farmers and artists, and with it, eroded systems of seed-saving, soil stewardship, and regional craft traditions. Today, many farmers express a desire to return to regenerative methods-not just for environmental reasons, but to reclaim autonomy. But doing so feels increasingly out of reach. Agricultural subsidies, market demands, and supply chains continue to favor monocultures and input-heavy cultivation, even as climate change renders these systems more fragile by the year.”

Similar patterns appear across the Global South: the logic of efficiency erases ecological resilience.

In recent years, “reshoring” has entered policy and brand vocabularies alike. The COVID-19 supply-chain crisis, coupled with rising nationalism and protectionism, made governments realise how dependent they’d become on globalised manufacturing. Both the U.S. and the EU have framed “strategic autonomy” as a goal, encouraging domestic or near-shore production. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan both hint at localised manufacturing as a matter of resilience, not just virtue.

True reshoring runs up against the same issue that drove offshoring in the first place: cost. In the 1970s, labour accounted for roughly 30 percent of a garment’s total production cost; today, it’s often less than 3 percent. This tiny margin reveals the structural imbalance of global fashion’s economics. To pay fair wages would require brands to re-evaluate not only prices but their entire model of profit extraction. Skilled labour is also scarce today as the skillset for garment production declined in demand when factories and mills closed. Between 1990 and 2011-80% of apparel manufacturing jobs in the United States disappeared.

As Mary Ping, designer of her independent label Slow and Steady Wins the Race, puts it: “The idea of bringing back American manufacturing—that will be a challenge because first of all I don’t even know where to find skilled sewers anymore. Even if you hire someone in the US for sewing, you will still have to pay minimum wage-which is how it should be but it’s higher than what most brands are paying now.”

Some movement is visible: European labels shifting small-batch production to Portugal or Turkey; U.S. companies experimenting with on-demand manufacturing in Los Angeles or Mexico. But these remain exceptions.

Fashion’s current structure, its trade rules, labour hierarchies, and supply chains, was designed for efficiency, not equity, or some, might argue, quality. Each policy that promised growth codified disposability: of garments, of ecosystems, of people. Due to its environmental toxicity and petroleum-derived textiles that do not biodegrade, fashion has become a less attractive investment asset class for those concerned with the earth’s future. If the next chapter is to be different, the structures, mindsets, and policies that shape the industry must be rethought and reinvented. Building brand resilience could mean deepening the collaboration between brands and producers, supporting farmers through volatility. Trade policy could reward ethical sourcing as much as low tariffs; transparency could become a standard, not a marketing tool. Systemic transformation will require shared responsibility along the value chain, industry-wide collaboration and investment in technology and innovation, and policy will play a key role in incentivising and supporting any industry evolution.

In the end, fashion is a language; visual signifiers that shape cultural and personal identity. Yet each garment also tells the stories of the hands that picked the cotton and worked in the factories and of the lands and water that fed the materials.