In 2019, Matty Feurtado took a journey twenty minutes from the Tajik border to the gateway of the Wakhan Corridor; the finger that stretches from Afghanistan’s palm, straddled by Tajikistan and Pakistan, reaching towards China.

When I first visited the Wakhi of northeast Afghanistan as a teenager, I interpreted their world as eternal and permanent. Returning with family photos four years later, under the control of the Taliban, taught me that nowhere is unchanging, especially in Afghanistan.

I had arrived with someone in mind, a girl called Soraya. When I met her, she was 19 like me and openly excited and optimistic about her examinations that would set her on the way to becoming a doctor. Taliban control had most likely doomed that education. I did not see her amongst the family members.

Her sister explained how life had been constricted and confined, another testimony in the story of apartheid against women.

‘We are not allowed to go to the prayer house. The women, it is always. With the men, they wait outside the door. They want us to be Sunni. I don’t leave the house anymore, just read. My exams were next year and I hope they are not cancelled.’

For many of the girls I spoke to, the only solution to imprisonment in their homes and the death of their aspirations, was to get out of the country. A slim hope for some and impossible to most. I asked about Soraya’s whereabouts.

On the day of the Taliban’s return in 2021, in Kabul– amidst suicide attacks and a mood of desperation– she was one of few who had boarded a flight to become a refugee somewhere outside her control. She was in Texas, studying nursing. They told me with laughter that they had seen a picture of her driving a car.

Now in possession of her WhatsApp number, I sent Soraya a family photo once I was somewhere with an internet service. She replied to say how much she missed them. This, the first of many meetings, got to the heart of why I chose to return here with family photos. At the very least, it seemed like the right thing to do, an unofficial contract of reciprocity where taking a photo is not a theft but a gift. Beyond this, this return would prove to have an ability to unify family and friends. In this case it was across continents, for a family severed by the war machine.

Often what the photographs emphasized most was absence.

Sometimes these family photographs unified people across time, connecting people with their past selves, creating points of comparison between a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ that the Taliban created. Using 35mm format on my first visit, and digital on my second, I accidentally reinforced this point. Yet some changes, made visible, were as natural as the seasons passing. Children aged, households grew, the river formed new banks. The Wakhan is different from much of Afghanistan. It largely avoided the worst of the wars over the centuries, out-of-sight, out-of-mind with no strategic or material value since the trading caravans of the silk road diminished. Where once it was a thoroughfare into east Asia, now being bordered on three sides it has become a cul-de-sac. The agro-pastoralist Wakhi people have managed to maintain their rockpool of Ismaili culture, despite being religious and ethnic minorities in a country with a history of both secular and religious violence.

The potential of running a highway through the corridor into China – a government eager to work with the new regime – has drawn the military into the corridor. While the project may bring economic opportunities to Afghanistan, its impact on Wakhi society remains uncertain. In this arid region, agriculture depends on precise water management and a population scale that could be disrupted by increased accessibility. Additionally, the Ismaili community in Afghanistan has historically maintained its religious practices through relative seclusion, which an infrastructure development is likely to impact.

Taliban presence has redefined the details of daily life.

It is deeply destabilizing to have homes surveyed by patrolling Taliban trucks and their private lives made public. The herding route a shepard has made undisturbed an entire lifetime is now interrupted by a checkpoint they must refer to. Villages are accented by oversized flags; it is an occupation both organizationally and in the visual composition of the area.

Many Wakhi view the Taliban as completely foreign. As Sunni Pashtun, the Taliban largely speak Pashtun and promote the language to be taught in the corridor, in the classic fashion of the victorious occupier. Ismaili music was banned, replaced with the Taliban’s own, playing it from Bluetooth speakers, imposing itself through sound and the sight of their Pashtun style Pakols.

The notion that the regime can speak on behalf of the country is contradicted by the diversity of culture, ethnicity, and islamic sects within the population. There were numerous massacres of Shia people and forced conversions of Islmailis – especially in the second half of the 20th century as distances between communities decreased.

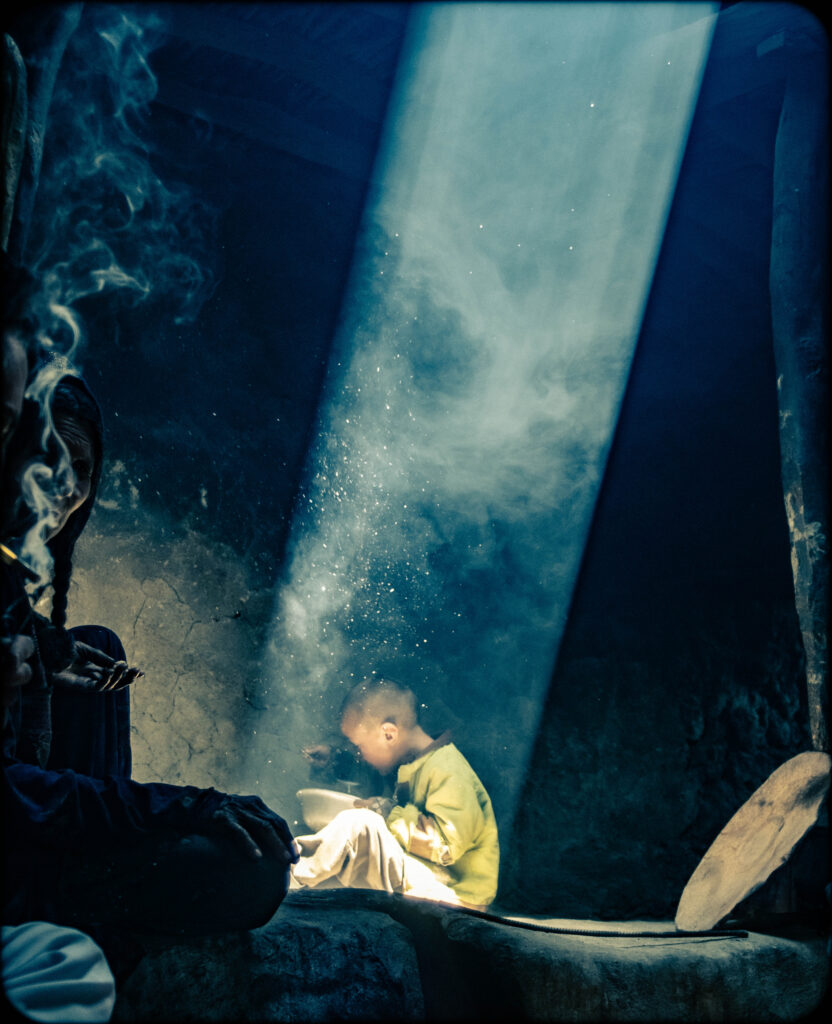

The boy’s house has since been moved due to flooding (2023)

“Why are the Taliban so afraid of women” – Nasib

Sat on her windowsill, Nasib remembered watching the trucks arrive in the same spot, where she now spends most of her time. Her aspirations to study business and set up a textile cooperative selling Wakhi clothes are shattered.

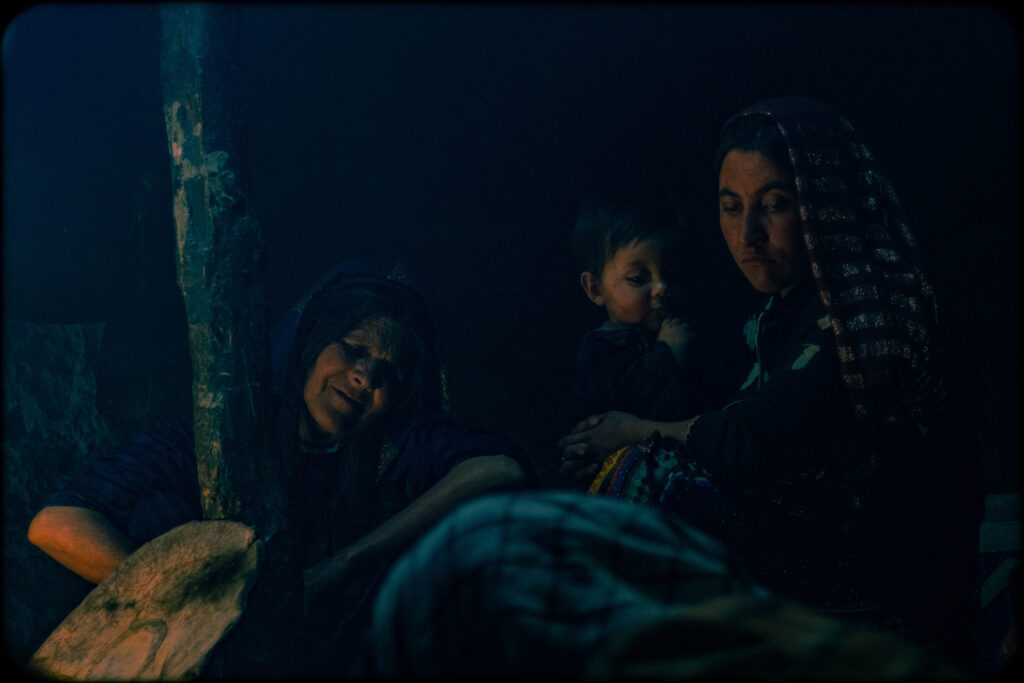

For Nasib, a young student, the presence of the Taliban garrison directly in front of her home immediately made her cautious to visit neighboring family members. Ismaili culture tends to be more relaxed about women moving alone– contrasting with the Taliban doctrine. Hair can be uncovered; indeed, veils and brightly hued clothing catch the sun and the eye. Education for women is encouraged by edicts from the Aga Khan, and to see a woman work the fields is not considered taboo.

I imagine even she could not predict that even to sit on this ledge and look out through a glass barrier would be deemed a privilege – one that could be taken away by the cruel edict of disallowing women from being seen in windows. This was the spot where she could ponder. Where a degree of imagination could synthesize. Where hope could be fostered. She could watch the harvest, at the very least always remaining in distant contact with her land, seasons and kin. She described looking at the stars and considering how these were the same stars that could be seen from ‘free countries.’

Looking at the photos I have brought, she desires me to take hers, but feels too watched for it to be safe. Instead, I photograph her windowsill, where she is absent. Perhaps one could imagine she has left.

In 2019, life was again narrated to me with descriptions of the changing seasons.

The deep snow and hibernation of winter; the thawing of the ground and immense effort to till the fields in spring for the crop of millet, lupin and rapeseed in Summer. The grazing of goats, sheep and yak in the higher passes during warmer weather and when they would shelter them within their own homes whilst snow raged outside. The festivals that marked the year, symbols painted on inside walls for the Islamic New Year, Eid and wedding ceremonies. These cycles gave an impression of an ageless ebb and flow.

Viewing my photos, people would sometimes narrate in the same way, through the seasons. Pointing out the work they would have be doing at that time, the differences in crops that year, or a new fence that had been erected.

In 2023, I arrived slightly later in the summer. The cereals grew bright yellow as a parting gift before the harvest – their flowering, a prize for the collective effort of creating and maintaining the irrigation veins that trickle soothingly throughout the valley. This beauty belongs to the Wakhi. There still is eternality in many ways. Efforts to remain within these patterns are an act of defiance against the changes the Taliban look to impose on the peaks of Bam-i-Dunya, the roof of the World.

Networks of quiet resistance

Similarly to how irrigation streams make hostile and arid lands arable, I saw the Aga Khan Development Network provide a different lifeblood during this volatile moment in time. Despite mistrust and hostility from the garrison, including the banning of female employees (which had at first been covertly defied), the local office has remained open. Healthcare and schooling, though basic, are still provided through this organization in lieu of government facilities.

NGOs across Afghanistan have struggled to navigate the Taliban’s capricious goalposts. The regime’s strength is called into question by reliance on foreign, secular aid. But they are reliant, especially given the gendered reduction in the workforce. The gap in the Taliban’s services creates an opportunity for the Wakhi to retain a unique level of autonomy and self-advocacy through the Ismaili Network. These networks, living in the spiritual, organizational, and online worlds are impossible to sever.

‘[The Taliban] don’t want us, but they need us, and we relieve the burden of the work they have to do here.’

An official from the Aga Khan Development Network

Witness and recognition

Realistically, my decision to return with photographs probably had the most significant bearing on me more than any Wakhi person. I count my time there as the most significant months of my life. I think it’s common for photographers to worry that their work lacks virtue – and still, it was deeply touching to have something to share with people, something that they could find value in. The act of remembering and recognising other versions of oneself is powerful. For people to look back on a different moment and become more aware of the changes within themselves, their families, their lifestyles and their landscapes.

In a moment of drastic change, where many Wakhi feel something inarticulable has been lost, reaching back through time in this way can create consciousness. In the face of a homogenizing regime, enforced militarily, the Wakhi defy their rulers by knowing their identity.