How would you describe your visual storytelling?

My narratives are focused on the territory’s socio-political issues, aiming to better understand our time.

What is your process like, how do you conduct your research?

My research practice starts from reading textbooks, selecting a topic, readings, collecting information and then narrowing or broadening the topic.

Due to my artistic practice which consists in the medium of photography, I then investigate how to communicate the theory part into images. Once all parameters are set, I may talk to local activists, people with different expertise and then start the production, the logistics of the project.

How do you perceive the relationship between humans and nature? What got you interested in exploring that relationship, and why do you think it matters?

Because I believe there is still time to change this geological epoch of great human impact on nature into an epoch that becomes historically remembered as a time period introspection where we “rethought” ourselves.

The control you use in your photography composition seems to symbolize the control of humans on earth. Is it intentional?

That’s interesting. Maybe you are right, or maybe it is, subconscious. Consciously speaking what you describe as control is related to aesthetics choices. In creating an image, I follow certain rules and take precise decisions on how every single inch of my image will turn out. I don’t go to places without a plan, everything is clear before the shooting process.

It is similar to a painter who paints a picture already knowing what size the canvas will be or as a theatre director who may decide that a scene should have a certain type of light and scenography.

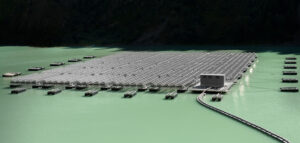

There are two facets that you are show-casing in your series, one is the urbanization of nature, but one also reflects the constructions around the solutions for the climate crisis like the PVC park or the recycling plant in Switzerland. What are you trying to express?

The aim here is to raise awareness on the acceleration in landscape transformation by creating a narrative as a tool to expand our own perspectives.

We must accept that some places won’t be as before. The reasons can be positive as is the case with renewable energy infrastructure that is built on suitable sites in order to transition quickly to low carbon energy.

Others will be transformed to include population growth and sprawling megacities.

I am interested in seeing how our state of mind relates to environmental transformation. Our society is changing faster than we can perceive and these images portray the symbolic moment of transition we are living.

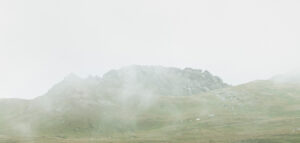

In addition to representing the transformation of landscapes through the energy revolution, you include images of natural environments and elements that are untouched by humans. Why did you choose to photograph intact nature as part of your series ‘Human domination on Earth’?

I want to represent natural resources which we still have today and that might be different tomorrow.

Eighty years ago, in Cervinia there was only a small church built in 1759, four or five houses around the church and a hotel. From 1936 this site became a Ski Resort, a field of architectural and engineering experimentation. There is an image in the series portraying the few natural landscapes left intact in Cervinia today, but again, it might be different tomorrow.

In your series, you captured the immaculate landscape of Serra d’Arga in Portugal, threatened by a possible exploration of lithium. What are the limits to technological and energy expansion?

Serra d’Arga is a very sensitive topic for me and for all of us who grew up in Alto Minho, Portugal.

The site is classified as Sites of Community Importance (SCI), part of the European Natura 2000 network and is the habitat of more than 500 species, and 180 wild animals including the Iberian wolf.

Yet, the site is under pressure. The limits should be set according to the environmental objectives in terms of preserving animal habitat, the safety of natural reserves, and acceptable in terms of scenic recourses among other impacts.

Wind turbines offer cheap and clean energy but often they bring challenges with them too, like the exploitation of land belonging to indigenous communities in South America or their repercussions on the natural habitat of animals. What do you think is missing in the conversation? How do you try to underline that in your photography?

I am underlining the environmental transformation, allowing the viewer to come up with their own opinion. I also try to raise awareness around the so called green-green dilemma and other issues that we are confronting in this conversation.

As for my perspective, some environments in suitable sites will change for a positive purpose – it is something that is inevitable. Others on sites that are not suitable will be transformed anarchically for the blind pursuit of economic growth. These blind actions are a serious danger to our planet and to human rights. Here we should be aware and ask ourselves how we can contribute to acting against it.

In my mind, this revolution requires a shift in thinking first (more based on de-growth theory of Serge Latouche), creating new moral and political principles.

Second, I believe in the kind of politics and public manifestations that, as main actors, can lead the way to a win-win approach that is mindful of human rights.

But again, I can’t offer solutions, I am not a philosopher, what I can do is offer work that raises questions. It is up to the viewer to come up with their own conclusions.

Which of these photographic journeys has had the strongest impact on you?

One of our biggest challenges throughout history has been inventing tools.

Almost everything we do today involves machines and having the chance to photograph and learn more on the PVC floating technology in Switzerland which creates energy for more than 6400 households had a strong impact on me. Without technological advances, this would not be possible.

If we look at technology over very long-time scales – as the early Bronze Age – we see that human evolution is linked to technological evolution. It is history and History fascinates me.

Another important experience was the Sarine river: at first glance, it looks like an intact natural resource, but if you look closer and ask what these white dots are, you will see a different facet of the image because these white dotes are 500 litres of chemical product that were mishandled.