On the world’s most densely populated island, a photographer portrays the vibrancy of community action in the face of climate adversity.

Cordero is a documentary photographer based in the Colombian Caribbean. A member of the Reojo Colectivo, and the 2025 recipient of the Vital Impacts Annie Griffiths Grant. His work spans personal projects, NGO assignments, and collaborations with international media outlets including The New York Times, The Guardian, Geo, The Washington Post, Vogue, El País, National Geographic. Social justice, climate change, and Caribbean traditions are recurring themes in his visual storytelling, and for the past seven-plus years, Cordero has been working on a long-term project in his home region about the inhabitants on Santa Cruz del Islote and their struggle against climate change.

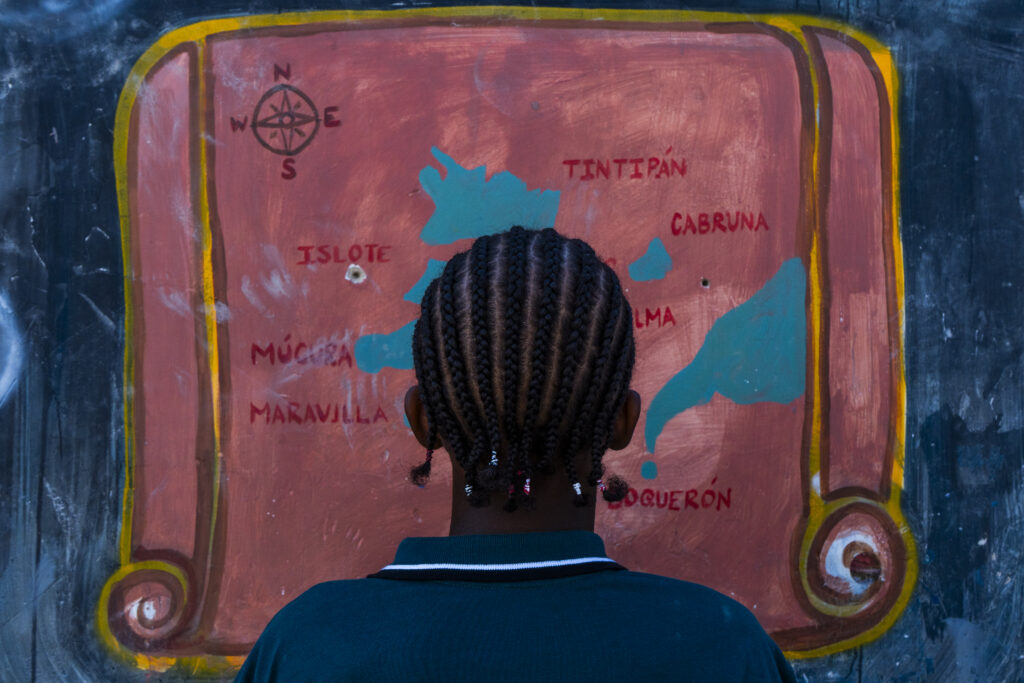

On an island the size of two football fields, in Colombia’s San Bernardo Archipelago, roughly 700 people live – and face the existential risk of rising sea levels, predicted to increase by 30-60 centimetres by 2040. The island’s Afro-Caribbean inhabitants, descendants of formerly enslaved people who settled here in the 19th century, now face the question of how to resist the loss of their ancestral lands. Icarus Complex’s Digital Producer, Madeleine Bazil, spoke to Cordero about this project, working intimately with communities, and climate storytelling at large.

Madeleine Bazil: I’m curious, how did your story in Santa Cruz del Islote begin? And how has it developed over time?

Charlie Cordero: What first drew me to Santa Cruz del Islote was my deep interest in vulnerable coastal communities in the Colombian Caribbean. I had already worked in places like Nueva Venecia, Tierra Bomba, and Bocas de Ceniza, and the Islote—because of its unique geography and sociocultural characteristics—was a place I felt compelled to explore. I was especially drawn to its collaborative way of life.

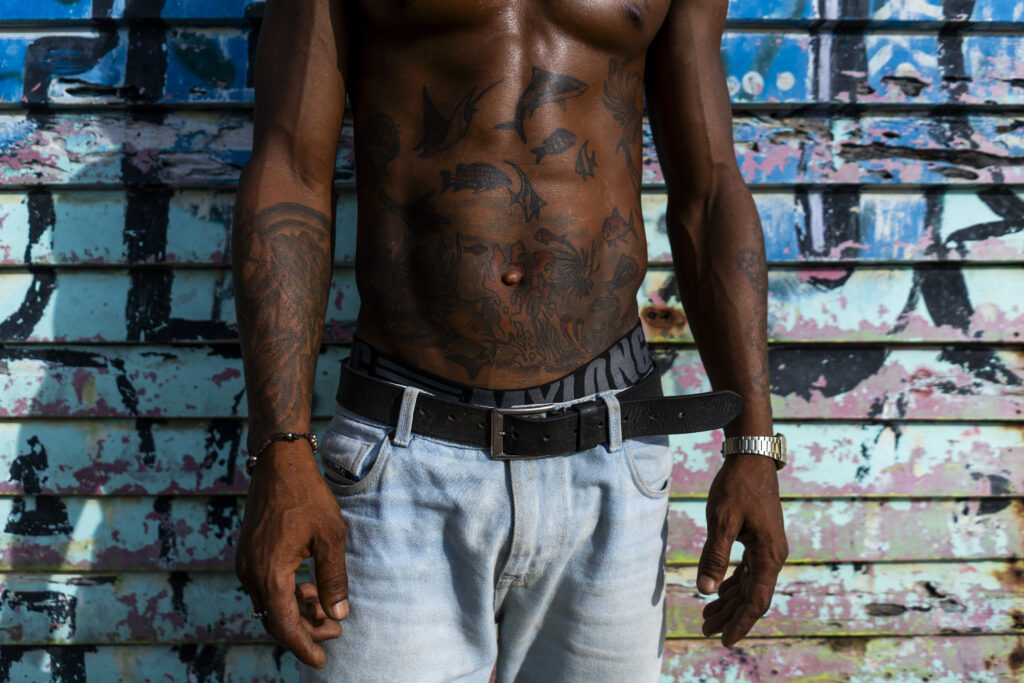

When I finally managed to visit as an independent photographer, I was fascinated by what I found: the vibrant colours, the contrast of the landscape, the people I met, and the everyday stories that emerged in every corner. But above all, I was struck by the resilience of its people and their deep love for their territory.

Over time, I began to see how climate change was increasingly affecting life on the island. Tides rose higher, erosion threatened neighboring islands, and unregulated tourism added pressure to a fragile ecosystem. That changed the course of the project: from documenting daily life to closely following the climate impacts and how the community organises to adapt and resist.

Tides rose higher, erosion threatened neighboring islands, and unregulated tourism added pressure to a fragile ecosystem.

MB: Something that strikes me about your work is how sensitive and conscientious it feels; it’s clear that you approach this community with care and respect. How do you build relationships and trust with communities in long-term, intimate projects like this one?

CC: For me, the most important thing is to build human connections before taking any photos. Listening, sharing, being present. Trust is something that’s built over time, and that has allowed me to enter intimate spaces with respect. I try to build genuine bonds—beyond the photographic work.

It’s also essential that the community feels connected to the project. I show them the material, we bring printed photos, and we talk about the process. It’s a two-way relationship. Today, I have close friends on the island. Going there is no longer an editorial assignment; it’s a personal commitment to them, to their story, and to their land.

It’s also essential that the community feels connected to the project. I show them the material, we bring printed photos, and we talk about the process.

MB: With climate stories like this which are so important and also really difficult, how do you tell a story in a way that feels hopeful and capable of shifting opinion? This is something we’re always thinking about at Icarus Complex…

CC: For me, telling these stories isn’t just about showing what’s being lost, but also what people are fighting to preserve. The climate crisis isn’t only an environmental emergency; it’s a human one, and that’s where real connection can happen.

I’ve learned that even in the middle of adversity, there is beauty, community, and resistance. In the Islote, for example, young people are planting mangroves to protect their territory. That, while small in scale, is an act of hope and power.

I don’t try to sugarcoat reality; I try to expand it. To show that people on the frontlines are already taking action. And that when those actions are shared with care, they can shift perspectives, awaken empathy, and spark collective responsibility.

I don’t try to sugarcoat reality; I try to expand it. To show that people on the frontlines are already taking action. And that when those actions are shared with care, they can shift perspectives, awaken empathy, and spark collective responsibility.

MB: Do you feel any particular responsibility or role as a photographer or storyteller in this current moment of climate collapse? How does photography fit in?

CC: Telling the story of the climate crisis requires sensitivity, context, and responsibility. We have to go beyond drama or exoticism and make visible the responses and solutions already emerging from local territories. To tell stories with dignity and deep listening. Photography mobilises, raises awareness, and makes issues visible. It’s a powerful tool.

In the Islote, I’ve witnessed a quiet but persistent struggle. I’ve seen the sea flood its streets, extreme heat disrupt routines, and unregulated tourism place strain on a fragile ecosystem.

Documentary photography has a unique ability to touch people, to stop us in front of what hurts—but also in front of what resists. It can turn empathy into action. In a world where climate change often feels distant or abstract, I try to bring it closer through familiar faces and daily moments that remind us we still have time to listen, to learn, and to act.

Documentary photography has a unique ability to touch people, to stop us in front of what hurts—but also in front of what resists.

MB: So what are you working on now, and what’s coming up next for you?

CC: Right now, the project is focused on the work of Eco-Sabios, a local ecological group [in Santa Cruz del Islote] committed to mangrove reforestation as a strategy to mitigate sea level rise and erosion across the archipelago.

Alongside Adrián, the group’s leader, we’re driving this initiative not just through documentary work, but through direct support: building partnerships, seeking funding, and finding ways to connect this local effort with a broader conversation around climate justice in the Colombian Caribbean. It’s a collective, intimate, and long-term process.

MB: Finally, a question for Adrián from Eco-Sabios: What do you want more people to understand about how the climate crisis is affecting the island? Or: what is something that you feel is important to communicate about the issue?

Adrián Caraballo: We live on an island that is at risk. Climate change, mangrove deforestation, and marine pollution are seriously affecting our marine ecosystems: corals, seagrasses, and all the surrounding biodiversity.

Our territory is part of a national park, and yet we face flooding, coastal erosion, and the very real threat of being displaced by rising sea levels. We feel we are being pushed to leave our home, not by choice, but by an environmental crisis that worsens every day.

We want people to understand the importance of the sea, coastal ecosystems, and the life that exists on this island. We aim to become a model of sustainability for the coast, to show that it’s possible to protect our environment and adapt to climate change through education, awareness, and a deep sense of belonging.

It’s essential that new generations understand they live in a unique place: a paradise worth protecting. That’s why we work to empower young leaders who will defend their territory through knowledge and love for their community.

We believe that only if the community and nature walk hand in hand can we build a sustainable future for Santa Cruz del Islote.

We aim to become a model of sustainability for the coast, to show that it’s possible to protect our environment and adapt to climate change through education, awareness, and a deep sense of belonging.